It is art’s most haunting and iconic face. A universal symbol of anxiety. It even has its own emoji.

Discover more about the fascinating story behind The Scream, and maybe a few things you didn’t know…

1. There is more than one version of The Scream

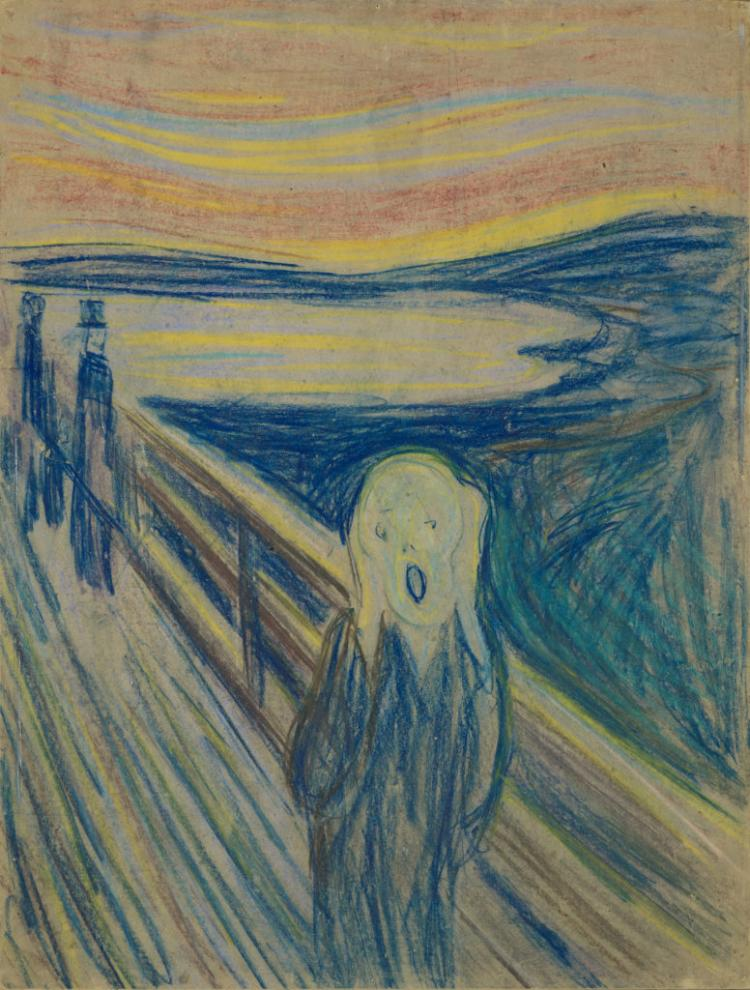

Pastel version of The Scream on display in the Munch Museum in Olso. Edvard Munch, The Scream. Pastel on paper, 1893. CC BY 4 The Munch Museum.

There are two paintings of The Scream (one at the Oslo National Gallery and one at the Munch Museum), two pastels and a number of prints. The 1895 pastel was auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2012 and reached £74 million, making it one of the most expensive pieces of art ever sold.

2. Munch first painted and displayed The Screamin 1893

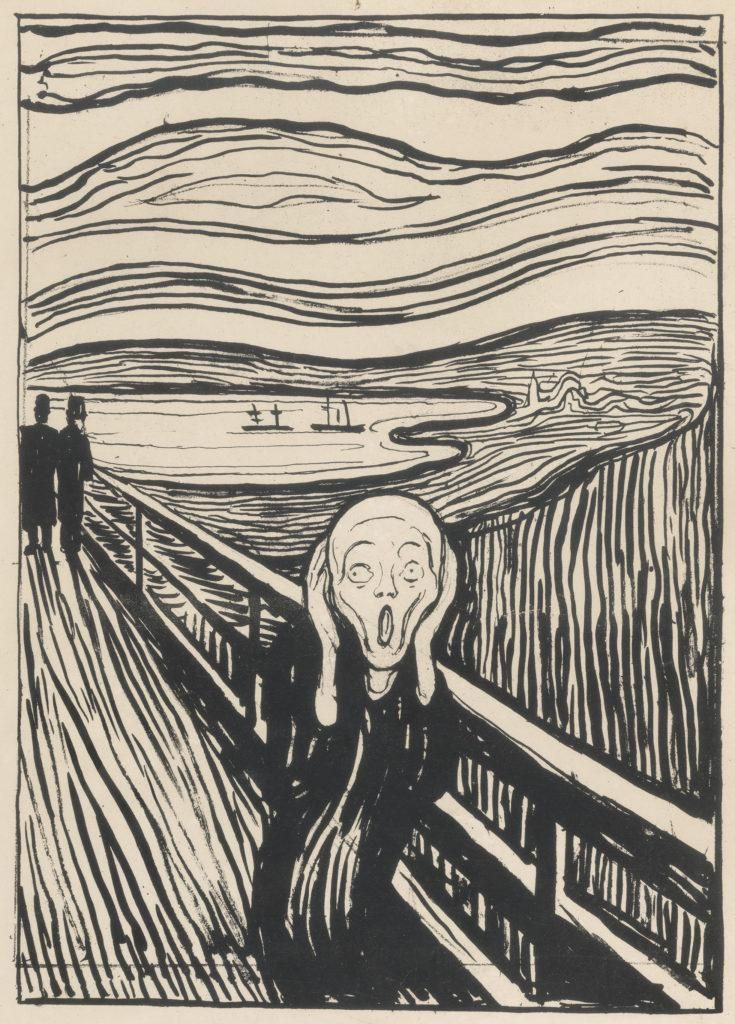

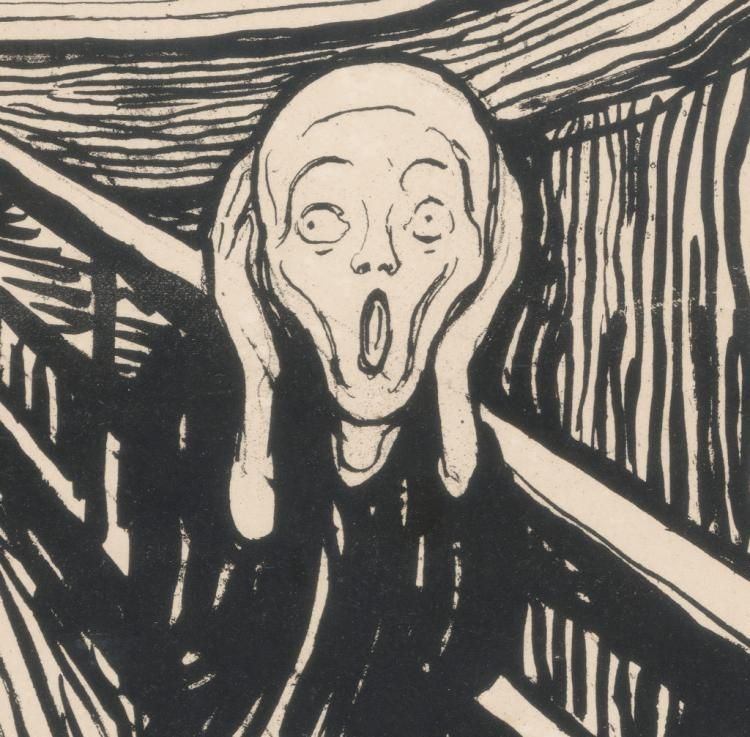

Edvard Munch, The Scream. Lithograph, 1895. Private collection, Norway. CC BY 4 The Munch Museum.

The first version Munch displayed was a painting. Two years later, he made a lithograph based on this work, with the title ‘The Scream’ printed in German below. The printed versions of the artwork were central to establishing his international reputation as an artist.

3. It was stolen not once, but twice!

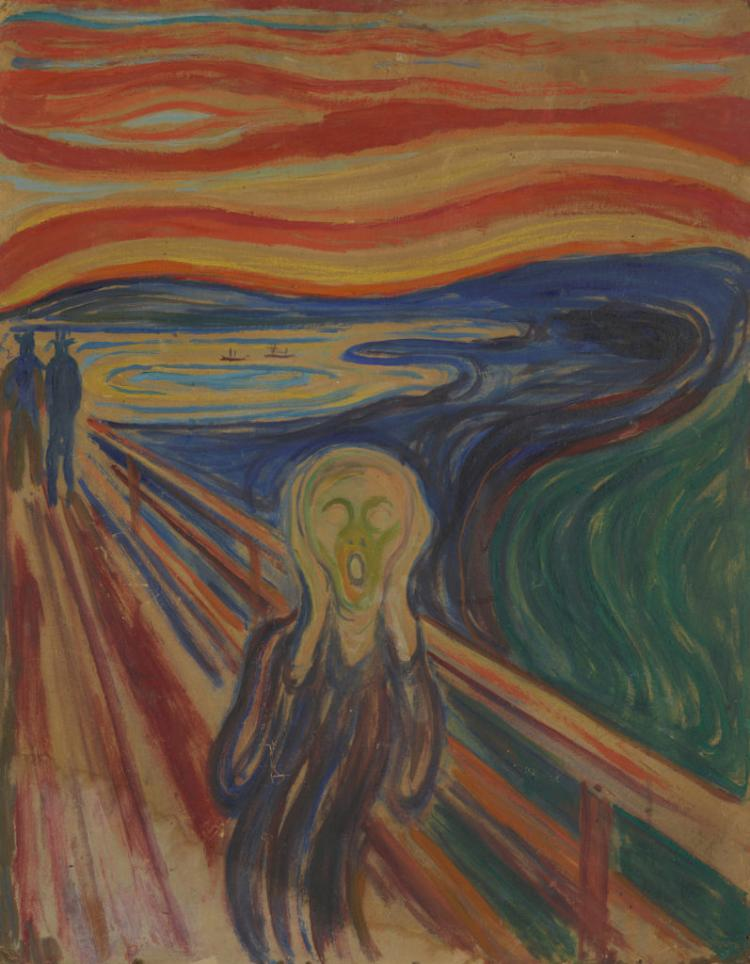

Painting of The Scream on display in the Munch Museum in Oslo. Edvard Munch, The Scream. Tempera and oil on paper, 1910. CC BY 4 The Munch Museum.

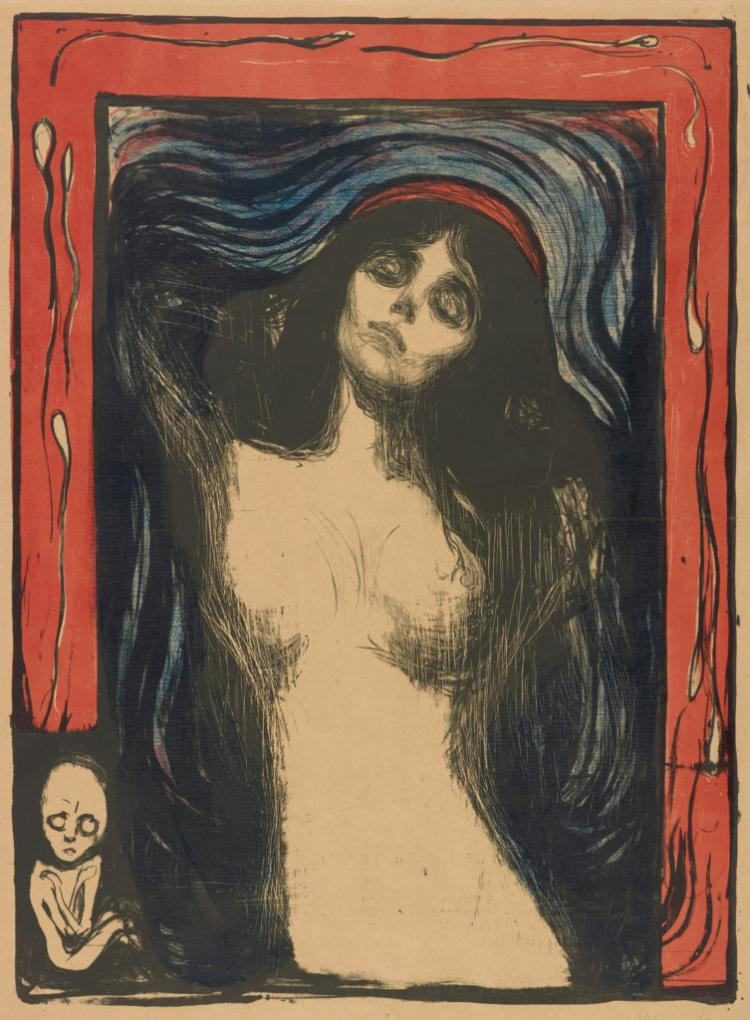

The first time was in 1994, when the thieves broke in through a window and made off with a painting of The Scream from the National Gallery in Oslo. Luckily, it was found and returned within three months. Armed gunmen broke into the Munch Museum in 2004, stealing a different version of The Scream, and also the artist’s Madonna. Both paintings remained missing until 2006, amid fears they may have been damaged in the process, and at worst, disposed of.

Edvard Munch (1863–1944), Madonna. Lithograph, 1895/1902. (CC) BY 4 The Munch Museum.

4. Ironically, the conservation process undertaken after the painting’s safe return to the Munch Museum might not have pleased the artist too much

Munch would have probably seen any marks from this period of the painting’s life as part of its artistic development. He wanted people to see how his works evolved and changed over their lifetime, and saw any damage they incurred along the way as a natural process, even leaving artworks unprotected outdoors and in his studio, stating ‘it does them good to fend for themselves’.

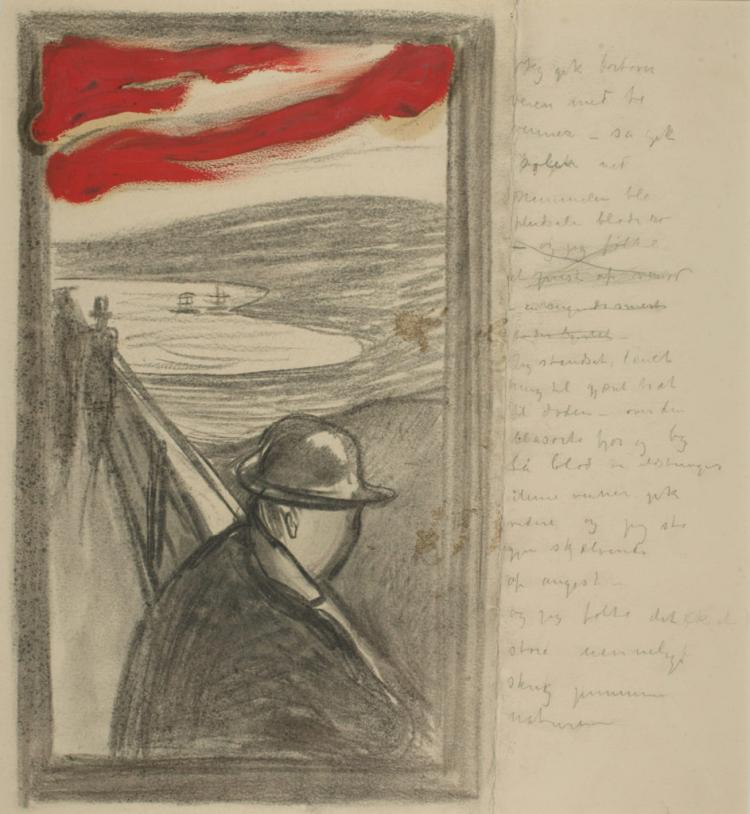

5. This sketch of Despair from 1892 came before The Scream,and perhaps shows the moment of isolation Munch felt just before the ‘scream ripped through nature’

Edvard Munch, sketch for Despair. Charcoal and oil, 1892. CC BY 4 The Munch Museum.

Munch describes this experience: ‘I paused feeling exhausted and leaned on the fence […] My friends walked on and I stood there trembling with anxiety’. There are a number of other artworks that accompany it – The Scream is the best known work from a powerful series of images which Munch called The Frieze of Life, first exhibited in 1893.

6. The figure in The Screamisn’t actually screaming

The actual scream, Munch claims, came from the surroundings around the person. The artist printed ‘I felt a large scream pass through nature’ in German at the bottom of his 1895 piece. Munch’s original name for the work was intended to be The Scream of Nature.

7. It was not intended to be a representation of an individual scream

Detail from Edvard Munch (1863–1944),The Scream. Lithograph, 1895. Private collection, Norway. CC BY 4.0 The Munch Museum.

The figure is trying to block out the ‘shriek’ that they hear around them (the work’s Norwegian title is actually ‘Skrik‘). The figure appears featureless and un-gendered, so it is de-individualised – and is perhaps one of the reasons why it has become a universal symbol of anxiety.

8. The Scream‘s powerful expression has proliferated into everyday life – and is one of only a handful of artworks to be turned into an emoji

😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱 😱

Another is The Great Wave by Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), which is part of the Museum’s collection. 🌊

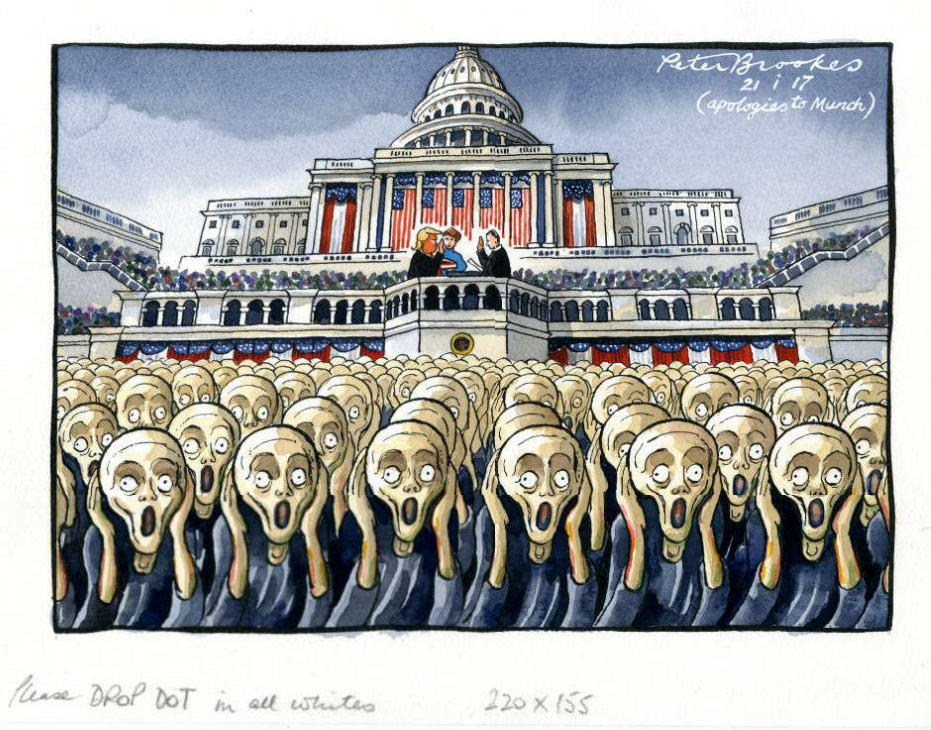

9. It has also made it into Pop Art and culture

From Andy Warhol to Manga, and Halloween masks to film, The Scream continues to fascinate people and influence visual culture to this day. British artist Peter Brookes used the image as the basis for this drawing published in The Times in 2017.

Peter Brookes. The Scream. 2017. Pen and black ink with watercolour and bodycolour.

10. The figure in The Screammay have been inspired by a mummy

The pose of the screaming head with hands cupped around it may have been inspired by the artist’s memory of a hollow-eyed, bound Peruvian mummy on display in Paris at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1889.

Source: The British Museum