From Campbell’s Soup Cans to the Velvet Underground and everything in between, a guide to the Pop master — illustrated with works offered at Christie’s

A is for Andrew

Andy Warhol was born Andrew Warhola on 6 August 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was the youngest of three sons to Slovakian immigrants, Julia and Ondrej. He would anglicise his surname (by dropping the final ‘a’) at the start of his artistic career.

B is for Brillo boxes

Among Warhol’s defining works as a Pop artist were the plywood sculptures he painted to resemble the cardboard packaging for Brillo soap pads. Stacked from floor to ceiling at his solo exhibition at Stable Gallery in New York in 1964, they prompted one bemused critic to ask, ‘Is this an art gallery or supermarket warehouse?’

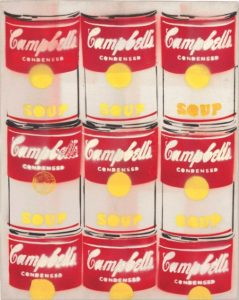

C is for Campbell’s Soup Cans

At the dawn of Pop Art, Warhol felt he was being left behind by peers such as James Rosenquist, who’d attracted attention for his images of 7 Up bottles. What was even more recognisable than a 7 Up bottle, Warhol wondered, before heading to the nearest supermarket to stock up on soup.

For his next show — in Los Angeles in 1962 — he produced silkscreen paintings of the cans of all 32 flavours of Campbell’s Soup. They were priced at $100 each, yet only six sold. The gallerist Irving Blum decided to buy that half-dozen back to keep the set together — a shrewd move, as it turned out. In 1996 he sold the complete set to MoMA for $15 million.

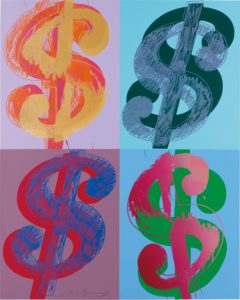

D is for Dollar bills and Death and Disaster

Warhol made no secret of his love of money. He said that a more advanced society than our own would simply hang cash on its walls rather than hang paintings. He also made dollar bills the subject of various artworks over his career. Most lucrative of the lot was the silkscreen canvas, 200 One Dollar Bills, which depicted a 10-by-20 grid of notes and fetched £26 million at auction in 2009.

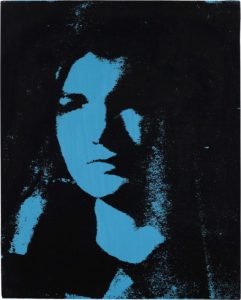

Warhol’s Death and Disasters series saw the artist penetrate the veneer of post-war American life to reveal the darker realities that lay beneath. Beginning in 1962, Warhol explored the theme of death through a variety of subjects, appropriating images from newspapers and magazines. Some of the photographs depict race riots, fatal car crashes, suicides, and nuclear explosions. Others are less obvious but no less powerful, such as the Electric Chair, Jackie and Knives series.

E is for Edie

Edie Sedgwick was the hard-partying model and society girl who became Warhol’s muse. The pair made 18 films together, the vast majority of them free-form, avant-garde pieces that had only a limited release in underground cinemas. Sedgwick’s cult status soon grew, though. Warhol dubbed her his ‘superstar’, and she was his companion at countless social outings in the mid-Sixties. She died in 1971, aged just 28, after a barbiturates overdose.

F is for The Factory and Flowers

The Factory was Warhol’s now-legendary New York studio, where he — and the city’s hippest artistic types, Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg among them — worked and played. It was here that Warhol shot many of his films; that assistants made prints under his direction; and that infamous parties raged.

Henry Geldzahler, Warhol’s friend and curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, declared it was he who ultimately inspired Warhol to begin the Flowers series: ‘… I looked around the studio and it was all Marilyn and disasters and death. I said, “Andy, maybe it’s enough death now.” He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “Well, how about this?” I opened a magazine to four flowers.’

The magazine was Modern Photography, which in mid-1964 published an article on a new Kodak home colour processing system. To demonstrate the effects of different exposure times and filter settings, the magazine’s editor included a foldout featuring a photograph of flowers she had taken which illustrated four variants of the image, each with slight colour differences.

G is for Guns

On 6 June 1968, the writer-actress Valerie Solanas, an occasional star in Warhol’s films, burst into The Factory, pulled a .32 automatic from her coat pocket and shot at the artist three times. She later claimed Warhol had ‘had too much control over her life’. He survived, but only after five and a half hours of emergency surgery. Warhol had to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. Firearms would become a regular subject in his art thereafter — in some 232 drawings, silkscreens and photographs, to be precise.

H is for Hoarding

Warhol was master of the mundane — but this extended far beyond introducing everyday subject matter such as soup cans into art. In the 1970s, he began assembling his so-called ‘Time Capsules’: boxes of ephemera, ranging from cookie jars and clothing to photographs, notes and newspapers. By the end of his life, he had amassed 610 such capsules. They now form part of the collection of the Andy Warhol Museum, in Pittsburgh.

I is for I. Miller

Having moved to New York from Pittsburgh in 1949, Warhol began his career as an illustrator for commercial brands. His biggest success came in the mid-Fifties with the women’s shoe company, I. Miller, whose flagging sales and reputation his quirky adverts boosted.

J is for Jackie Kennedy and Jane Fonda

‘He was handsome, young, smart, but it didn’t bother me that much that he was dead,’ Warhol once said of President John F. Kennedy. ‘What bothered me was the way television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad. It seemed like no matter how hard you tried, you couldn’t get away from the thing.’ In the aftermath of the President’s assassination in 1963, the artist began working on a series of portraits of Kennedy’s widow, appropriating media imagery to produce more than 300 works featuring the former First Lady.

Always good for a quote, Warhol once quipped: ‘I am a deeply superficial person’. Some critics found his personality — and his art — shallow, pointing especially towards his ‘society portraits’ from the Seventies. Jimmy Carter, O.J. Simpson and Jane Fonda were among the stars who sat for Polaroid photographs, which he later converted into silkscreen canvases. These weren’t so much artistic analyses of fame, as his visions of faded stars in the Sixties had been (see ‘K’ and ‘M’) — rather, these appeared to be straight homage paid by one celebrity to another.

K is for ‘The King’

As in Elvis Presley. Fame was one of Warhol’s chief preoccupations, and in the one-time ‘King of Rock’n’Roll’ — being eclipsed in the early Sixties by a new generation of performers like The Beatles — the artist found fascinating subject matter. Warhol relied on a publicity still of Elvis from the film Flaming Star and, in various works in various ways, repeated it across a canvas. Each Elvis figure tends to dissolve into another, symptomatic of the real Presley’s decline. Was Warhol perhaps simultaneously suggesting the continual snapping of a paparazzo’s camera, or even the idea that celebrities had multiple, manufactured personae and could never truly be themselves?

L is for Lichtenstein and Liz

Roy Lichtenstein, that is — Warhol’s Pop Art peer and rival. Both began the 1960s with imagery inspired by comic books, in Warhol’s case a display window at the department store, Bonwit Teller, featuring subjects such as Popeye and Superman. For his part, Lichtenstein went on to forge a whole career out of comic-book and cartoon imagery with works such as Wham!, Drowning Girl and Look Mickey. It was Lichtenstein’s runaway success that soon prompted Warhol to look elsewhere for his subject matter: namely the supermarket.

As one of the greatest cinematic icons of the latter half of the 20th century, Elizabeth Taylor was a fitting subject for Warhol’s celebrity-oriented art. Indeed, of all the many famous stars that Andy Warhol knew and painted, he seems to have held Elizabeth Taylor in especially high regard, seeing her as the absolute epitome of glamour. They became friends in the late 1970s and 80s, and Warhol quipped as a choice of afterlife, he would like to be reincarnated as a ‘big ring’ on Taylor’s finger.

Taylor first appeared in one of his tabloid paintings, Daily News, a painting documenting her illness of 1961. She resurfaced in allusion only, in The Men in Her Life, a work based on a 1957 photograph, which included both her current husband, Mike Todd, and her future one, Eddie Fisher. Most often, however, Warhol was intrigued with Liz as Hollywood starlet: he multiplied images of her characters in National Velvet and Cleopatra, or more simply portrayed her celebrated beauty in numerous full-face portraits

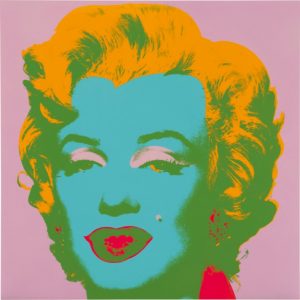

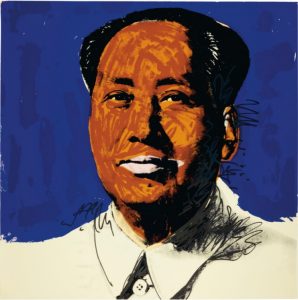

M is for Marilyn and Mao

Following her death in August 1962, Warhol made a series of paintings in tribute to Marilyn Monroe, based on a publicity still from her 1953 film Niagara. He often repeated the still across the same work, evoking both a film frame and Monroe’s ubiquitous presence in the media. In perhaps his most famous example, the Tate-owned Marilyn Diptych, the images of Monroe begin in luscious colour on the left before fading into ashen tones, and finally oblivion, on the right: as if reflecting the star’s fragile mortality.

Andy Warhol’s 1972 portrait of Mao Zedong marked the artist’s return to painting after a short period during which he had concentrated almost exclusively on filmmaking. His choice of Chairman Mao tapped into the easing of relations between the United States and China after President Nixon’s visit to communist China in February of that year. The American public became quickly accustomed to the visage of Chairman Mao, and Warhol mined the myth surrounding the man synonymous with absolute political and cultural power.

Both Mao and Warhol understood the force that an image could exercise, and just like the Chinese leader, Warhol’s rendition of an authoritarian ruler was anchored in the media’s power to create, canonise, and commodify personas for collective absorption. By choosing the leader of the world’s largest communist country as his first subject on returning to painting, the foremost chronicler of the consumerist society creates a distinctly Warholian fusion of East and West. And by adopting a an updated version of his silkscreen method of painting, Warhol suggests that Mao’s popularity could be as much the product of highly effective marketing as the cans of tomato soup or Coca-Cola bottles.

N is for Nixon

Warhol wasn’t the most political of artists, but his support for Democrat candidate George McGovern in the 1972 presidential elections was unstinting. His tactic: to create a poster portrait of the Republican candidate and incumbent president Richard Nixon in a sinisterly pale green colour that suggested he was a devil. The glaring yellow eyes and mouth, which seems to be on the point of foaming, add to the sense of the demonic.

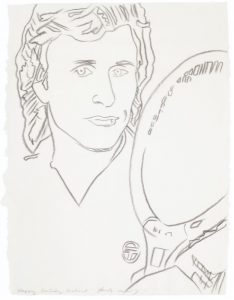

O is for O.J. Simpson

In the spring of 1977, the businessman, art collector and sports fan Richard Weisman commissioned Warhol to depict 10 of the most famous sports stars of the era in 40 x 40 inch, multi-coloured portraits. The list included Muhammad Ali, Jack Nicklaus, Pelé, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Chris Evert and the American football star and aspiring actor O.J. Simpson. The artist first met Simpson in Buffalo in October of that year, describing him as being ‘movie-star handsome’ and taking 46 shots on his Polaroid Big Shot camera. Four shots of each athlete were subsequently selected to be made into screens.

The Complete Athletes Series saw Warhol returning to familiar territory, although instead of Campbell’s Soup Cans and Coca-Cola bottles, his fascination with consumer culture was now directed towards the sports stars of the day.

P is for Popism

This was the name of Warhol’s memoir about his life in the Sixties, which he penned in 1980. It was, in fact, largely ghost-written (thanks to the efforts of his friend Pat Hackett), but there are still plenty of pithily Warholian observations. Of Pop Art, he said: ‘The idea behind [it] was that anybody can do anything.’ Warhol felt that, after centuries of the domination of elite tastes, Pop was a movement that finally democratised art, for artists and viewers alike.

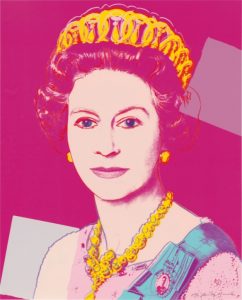

Q is for queen

In the mid-Eighties Warhol created a portfolio of screenprint portraits of the world’s four reigning female monarchs: Queen Elizabeth II of England, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Queen Ntobi Twala of Swaziland. Rumour has it that the English monarch was so fond of her depictions that she had an edition bought for the Royal Collection to mark her Diamond Jubilee in 2012.

R is for race riots

A series of silkscreen paintings from 1963-64 derived from three photographs Warhol had seen in Life magazine of police dogs attacking civil rights protesters in Birmingham, Alabama. These images of political oppression and racial segregation offered another diagnosis of America, complementing his ‘Death & Disasters’ series. In many cases, Warhol repeated his photographic source across the canvas — to such an extent that we start to see a pattern rather than figurative representation. Media overexposure, the point goes, can desensitise us even to the most shocking imagery.

S is for silkscreen

This was Warhol’s trademark technique, one that particularly appealed because it allowed him to ‘paint like a machine’, removing evidence of the artist’s hand in favour of a mass-produced look. The process (akin to that used in the making of T-shirts and greetings cards) involved stencilling photographs onto an acetate plate, which was then transferred onto a meshed screen. Paint was duly applied through the mesh and a design transferred onto canvas. (In the case of silkscreen prints, as opposed to paintings, the process is much the same — except that ink and paper substitute for paint and canvas.)

T is for TV

At the turn of the 1980s, Warhol embraced a new format — television. He insisted it was ‘the medium [he’d] most now like to shine in’, wowed by its ability to communicate far and fast. His first effort was a 10-show series about fashion for a Manhattan cable channel. His next, Andy Warhol’s TV, featured interviews with celebrities, from Debbie Harry to Stephen Spielberg. His big televisual break, though, came with Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes, which screened nationwide on MTV. It ran for just four episodes — before Warhol’s death in 1987, aged 58, from complications after a gall bladder operation.

U is for Uccello

Warhol’s isn’t a name you usually associate with Florentine Old Masters, but in the Eighties he created silkscreen adaptations of many Renaissance masterpieces — including Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Paolo Uccello’s St George and the Dragon.

V is for The Velvet Underground

Warhol briefly managed rock group The Velvet Underground. His knowledge of music was limited to say the least, but he didn’t let a small matter like that get in the way. Warhol designed the now-famous cover for the band’s debut album, complete with provocative banana and accompanying text instruction to ‘peel back and see’. Warhol also thrust the Velvets to the heart of his Sixties event-spectacular, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a template for multi-media rock concerts today, featuring innovative lighting, film projections, the Velvets’ music — and sporadic whip dancing.

W is for worship

As a young man in Pittsburgh, Warhol developed a fondness — bordering on obsession — for Truman Capote. Initially he bombarded the author with phone calls and fan mail, with such regularity that Capote’s mother intervened and demanded he stop. Then, when Warhol moved to New York, he often hung around outside Capote’s house for hours on end waiting for a sight of his idol. His first exhibition in New York was a set of 15 drawings inspired by A Tree of the Night and other short stories by Capote.

X is for X-rated

In the Seventies, Warhol’s film work moved on from the avant-garde to schlock horror. He produced two films, Blood for Dracula and Flesh for Frankenstein, both of which were given an X rating.

Y is for YouTube

Warhol was more than an artist; he was also a prophet. With his most famous quote — ‘In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes’ — he predicted the rise of reality television and social media in one fell swoop. Since his death, he has also become a hit on YouTube — one of his intentionally banal films, of him eating a hamburger, has reached more than 1.6 million views on the channel.

Z is for Zebra

Warhol was a well-known animal-lover: he was regularly accompanied about New York by his beloved dachshunds, Archie and Amos, for example. In 1983 he produced a series of silkscreen prints called ‘Endangered Species’, featuring psychedelically colourful renderings of 10 animals at risk of extinction, including the Siberian Tiger, Giant Panda and Grevy’s Zebra. They were commissioned by art dealers Frayda and Ronald Feldman to highlight these species’ plight. Warhol duly conferred on them the iconic status he had on his celebrity subjects of the past.

Andy Warhol ‘Campbell’s Soup’ 1968

Andy Warhol ‘$’ 1982

Andy Warhol ‘Jackie’ 1964

Andy Warhol ‘Marilyn Monroe’ 1967

Andy Warhol ‘Mao: one print’ 1972

Andy Warhol ‘Vitas Gerulaitis’ 1978

Andy Warhol ‘Queen Elizabeth II’ 1985

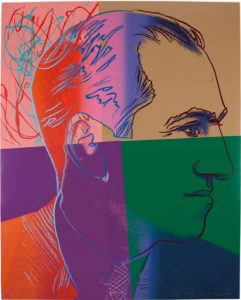

Andy Warhol ‘George Gershwin’ 1980

Source: Christie’s