A look into the iconic works of one of America’s most celebrated painters of the 20th century as he captured the melancholy of urban life

Coffee shops and late-night diners, hotel rooms and roadside gas stations, empty store fronts and offices after hours – Edward Hopper’s paintings are quintessentially American. By portraying the country’s everyday citizens in their natural habitat, Hopper is revered as one of the most important stateside artists of the 20th century. But behind that quaint slice of American apple pie life, something darker lurks: isolation, voyeurism, the silent sound of lonely hearts left spent and wanting.

Edward Hopper, New York Movie, 1939, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Hopper’s New York Movie is a particularly striking composition. As the moviegoers are seated in the partially-darkened theatre, engrossed in what is unfolding in shades of black and white upon the screen, a woman in blue stands in dejected contemplation to the painting’s right-hand side, head lowered, the yellow beams of the wall lamp spilling diffused onto the strands of her blonde hair. The piece is split down the middle in terms of layout and lighting, resulting in a definite separation of the subject and crowd, who sit oblivious to her sorrow. There is a clever inversion at play here. The woman in blue is the one in metaphorical darkness, isolated from those cast in actual shadow, who are likely enjoying themselves without a care in the world. The red curtain that hangs narrowly open, revealing a set of stairs, also adds an element of foreboding to the piece. Hopper is truly the master of the short-story in oil on canvas; the viewer can profoundly sense the subject’s plight, and even though they may not be privy to the particulars, they inherently understand what is unfolding before them.

Edward Hopper, Eleven A.M., 1926, oil on canvas, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

While Hopper possessed a slight penchant for painting nudes, they differ significantly from most in the fact that they are as much about the psyche of the subject as their physical attributes. They are more than simply a study of the body, or an aesthetical addition to a classical scene. Eleven A.M. serves as an apt example. The subject is seated in a blue boudoir chair, skin as pale as milk. There is a natural beauty to be appreciated in the curves of the calves and lower abdomen, in the way her unbrushed hair falls messily in front of the shoulder. But the viewer is also just as preoccupied, if not more so, with the more subtle details of the piece. Why is the subject clad solely in her shoes? And even if upon first glance she appears serene, enjoying the late morning sun, doubt slowly begins to creep in. Does there seem to be a slight tension in the way her hands are clasped? In how she leans forward gazing intently out of the uncurtained window? Or is it simply the genius of Hopper’s ability to make the mind wonder and wander?

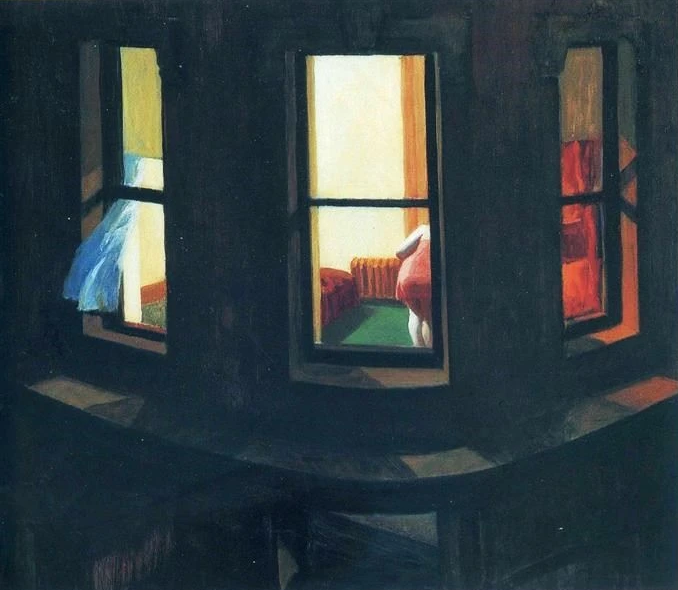

Edward Hopper, Night Windows, 1928, oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Hopper’s Night Windows is a piece that may seem relatively light-hearted. A woman is going about her business on a sultry summer night, bending over to perhaps pick something up, subsequently giving the viewer a glimpse of her shapely derrière. But the viewer’s point of view is also very likely someone else’s. Once this realization has dawned, Night Windows takes on a completely different feeling, one that is much more sinister. There is an anticipation brewing in the billowing lace curtain in the left-hand side window, and a darkened desire exudes from the ruddy fire-like glow found in the one on the right-hand side. When will the peach-colored dress be peeled from her lily-like flesh and fall to the pool-table green of the carpeted floor? And what will unfold after?

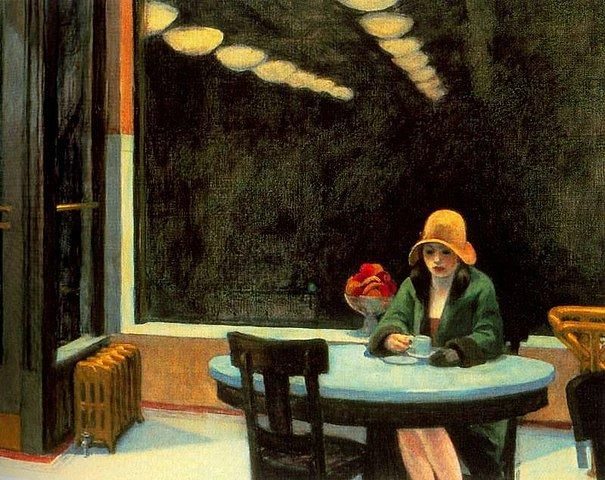

Edward Hopper, Automat, 1927, oil on canvas, Des Moines Art Center

Automat is one of Hopper’s most iconic pieces, and understandably so. The 1920’s fashion the subject is dressed in, the way her eyes are cast down demure towards her coffee cup, the smooth skin of her legs pressed together beneath the table. It is the epitome of style, and holds much aesthetical appeal. But Automat is also a portrait of an immense isolation – a theme that is not uncommon throughout Hopper’s oeuvre, and one that the artist executes in such a subtle way, that is often difficult to pinpoint exactly how he achieves it. One of the techniques that Hopper employs can be found in the composition. He often includes a little more than is ample empty space, which serves to insinuate that the subject is very much alone – both physically and psychically. Automat also holds other subtle cues: the subject’s left hand is still clad in a glove, and she hasn’t removed her coat – perhaps it is an exceedingly cold evening, but that possibility is somewhat discardable due to the heater found in the painting’s lower left-hand side. Perhaps stopping for an espresso is too fleeting to warrant getting too comfortable – which is certainly the nature of the coffee. Or, perhaps, and most-likely so, she is just too miserable to bother. She certainly holds more than a mere hint of melancholy in her countenance. Even the piece’s title is a clue to the isolation inherent within the confines of the canvas, for an automat is an automated café or restaurant, one that is devoid of waiters and waitresses. But even though it may be missed upon first glance, the most obvious component of the painting that tells of the subject’s solitude actually takes up majority of the composition. Whether the automat is situated in a subway station, or its ceiling lights are reflected in the plate-glass window, the darkness that seethes around the subject pulls her into a desolate tunnel of nihilistic darkness.

A six-word short story exists that is commonly attributed to Ernest Hemingway. This “story”, in the form of a classified newspaper advertisement, is extremely visceral, and possesses a poignancy that many novels fail to achieve in hundreds of pages of prose. It goes as follows: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” Nothing directly tragic is contained in its words, they merely state that an item of clothing is for sale. Its profound power lies in what is implied, what the reader’s imagination runs rampant with, what is implicitly understood. Edward Hopper’s genius is of similar ilk. His pieces often spark the same small fire of the mind, and if the viewer gives the flames just a little time to spread, they can grow into a raging inferno.

Written by Benjamin Blake Evemy

Source: Mutual Art