Unrecognized during her lifetime, at a time when opportunities for women were limited, Henrietta Rae’s commitment to her work is an inspiring tale of resilience

Victorian society was marked by strict ideals regarding gender. Regulated by separate spheres, men were the providers and decision makers, while women were the “Angel in the House”. If man was the pillar which held society high, then women were there to support that pillar. This was no different in the art world. Since man was superior, so were his natural talents. English art critic, writer, and philosopher, John Ruskin, wrote in 1865 that women’s “intellect is not for invention or creation.” This naturally made it extremely difficult for female artists of the era to be taken seriously, but some did manage to break away from the hearth and into hallowed halls of the Royal Academy of Arts. One of those artists was Henrietta Rae.

Henrietta Rae, ‘The Sirens’, circa 1903, oil on canvas, private collection

Henrietta Emma Ratcliffe Rae was born in Hammersmith, London, on December 30, 1859. She began her formal studies in the field of art at age thirteen at the Queen Square School of Art. After two years she continued her studies in the Antique Galleries of the British Museum. While still at the museum, she was accepted into Heatherley’s School of Art, making history as the first woman ever admitted to the institution. While there, she met her future husband, fellow art student, Ernest Normand. When the couple married in 1884, Rae decided to keep her family name, as she had already started to garner a reputation as an artist (despite this fact, she would often be referred to as Mrs. Ernest Normand by others).

Henrietta Rae, ‘Azaleas’, 1895, oil on canvas, private collection

An unwavering dedication to her art was a constant for Henrietta Rae. She was to be taken seriously, and no matter the inherent odds against her because of her sex, she refused to waver in the sentiment. She planned to gain admittance to the Royal Academy of Arts, and she would. But it would not be a simple feat by any means. It took Rae five or six attempts until she was finally accepted in 1877. While there, she would study under Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who would have considerable influence on her work.

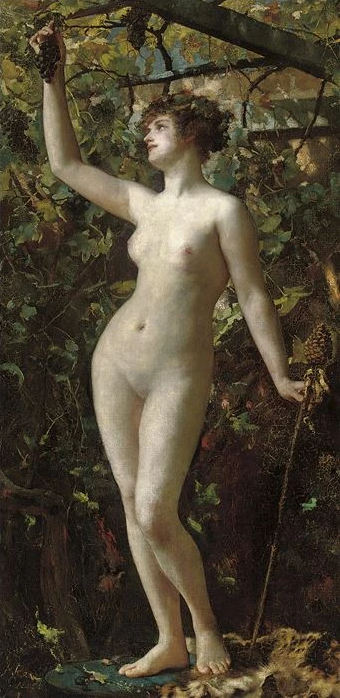

Henrietta Rae, ‘A Bacchante’, 1885,

oil on canvas, private collection

In 1885 Rae not only exhibited her first nude at the Royal Academy, but what was the first nude piece painted by a woman to ever be exhibited at the institution. A Bacchante, 1885, depicts a priestess of the Greco-Roman god of wine, staff in one hand, a cluster of grapes in the other. Perhaps somewhat stoic with its subject posing statue-like while carrying out a task, the piece still aptly showcases the technical skill that Rae would go on to further refine and master. The piece caused quite a reaction when exhibited, with Rae receiving a comment stating that she should refrain from showing such works again in public.

Rae and Normand lived in Holland Park, Kensington, an area popular with artists of the era. Despite the fact that Rae was an equal upon the canvas, it did not stop a lot of criticism which manifested in ways that were decidedly pernickety. In a well-known anecdote, Pre-Raphaelite Valentine Cameron Prinsep, while visiting the couple, in an act of blatant disrespect, added a dash of paint to one of her pieces with his thumb, and, not being one to not stand up for herself, she retaliated by “accidentally” burning his hat on the stovetop. One could argue that these “criticisms” did not necessarily stem from Rae being female, but when the artist exhibited the piece Psyche Before the Throne of Venus at the Royal Academy in 1894, direct reference was made to her sex in a review published in the Magazine of Art, and as praised as the piece was in the publication, it was certainly backhanded: “This elaborate composition, full without being crowded, graceful in the drawing of its figures, dainty in its appreciation of feminine beauty, delicate in its tones and tints, is a work we hardly expected from a woman.” As ironic as the praise is, it was not meant to be taken as sarcasm, but instead earnestly. Although despite its inanity, this example is of extreme importance, as it aptly shows the bias and hypocrisy that female artists had to endure during the Victorian era. For who would be more capable at expressing the beauty of the feminine, than females themselves?

Henrietta Rae, ‘Hylas and the Water Nymphs’, circa 1909, oil on canvas, private collection

In 1897, for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, Rae organized an exhibition of work by woman artists. By doing this, Rae was not only gaining exposure for other female artists, but she was asserting her position as a working woman. The trials and tribulations that Rae herself faced because of her sex have been somewhat downplayed in art history, but she was deeply affected by them. In an 1899 essay published by Woman’s Life titled “How to Succeed as an Artist”, Rae wrote in regard to females pursuing the career “never to become artists at all”. This not-exactly encouraging advice speaks volumes, as alongside the struggle to live, the ill-effects that the career had on her health, a large part of it came from her experiences as a female artist.

Henrietta Rae, ‘Miss Nightingale at Scutari’, 1854 (commonly known

as ‘The Lady with the Lamp’), 1891, colored lithograph, Wellcome Library, London

Henrietta Rae died on January 26, 1928. Even though she may never have quite achieved the artistic status that she truly deserved during her lifetime, Rae’s work is finally starting to gain the respect it has always deserved, and her pure determination to persevere in a world that viewed her as a lesser creature, is a testament that should serve as an unadulterated inspiration to others who are driven by relentless creative desire.

Written by Benjamin Blake Evemy

Source: MutualArt