Hàm Nghi (1871-1944), real name Nguyễn Phúc Ưng Lịch, was the eighth king of the Nguyễn Dynasty, the last feudal dynasty in Vietnamese history. Ưng Lịch lived in poverty and rusticity with his mother since childhood, unlike his two older brothers in the palace. On August 2, 1884, at Thái Hòa Palace, he was enthroned at the age of 13 by the regents who advocated anti-French policies, Nguyễn Văn Tường and Tôn Thất Thuyết. Hàm Nghi was a person of sufficient lineage, but had not yet been tainted by the wealthy life of the capital, and most importantly, Nguyễn Văn Tường and Tôn Thất Thuyết could easily orient the king toward the great cause of the country. The spirit of the young king who had just ascended the throne unintentionally rekindled the pride of national independence, ringing the bell to awaken his people. Despite the French troops stationed in the ancient capital, King Hàm Nghi and the court of Huế still showed a confrontational attitude.

In early July 1885, after the Nguyễn Dynasty’s army failed to attack the French at Mang Cá fort, in the Tân Sở mountains, King Hàm Nghi issued Cần Vương proclamation, calling on scholars and farmers to rise up against the French to gain independence.

The people responded to the movement in great numbers. In the book “L’Empire de l’Annam”, Gosselin wrote: “His name became the flag of national independence… From North to South, everywhere the people rose up at the call of the king.” Unfortunately, because the forces were scattered, they were isolated. In September 1888, the king was arrested for uprising, when he was 17 years old.

At 4:00 a.m. on November 25, 1888, King Hàm Nghi was taken by ship to Lăng Cô. On Sunday afternoon, January 13, 1889, the king arrived in the Algiers, capital of Algérie. Throughout his exile, the former king never lost his love for his country. At first in Algiers, he refused to learn French because he thought it was the language of invaders. However, the French at that time wanted to prove the opposite, so they had the prince’s clothes made in the royal shop in the French style and forced him to wear only those clothes. After dressing the king in European clothes, they took pictures of King Hàm Nghi wearing French prince clothes and sent them to An Nam. The colonial government at that time wanted to convey the message to the people in the country through the pictures that the king they respected had truly submitted to the French.

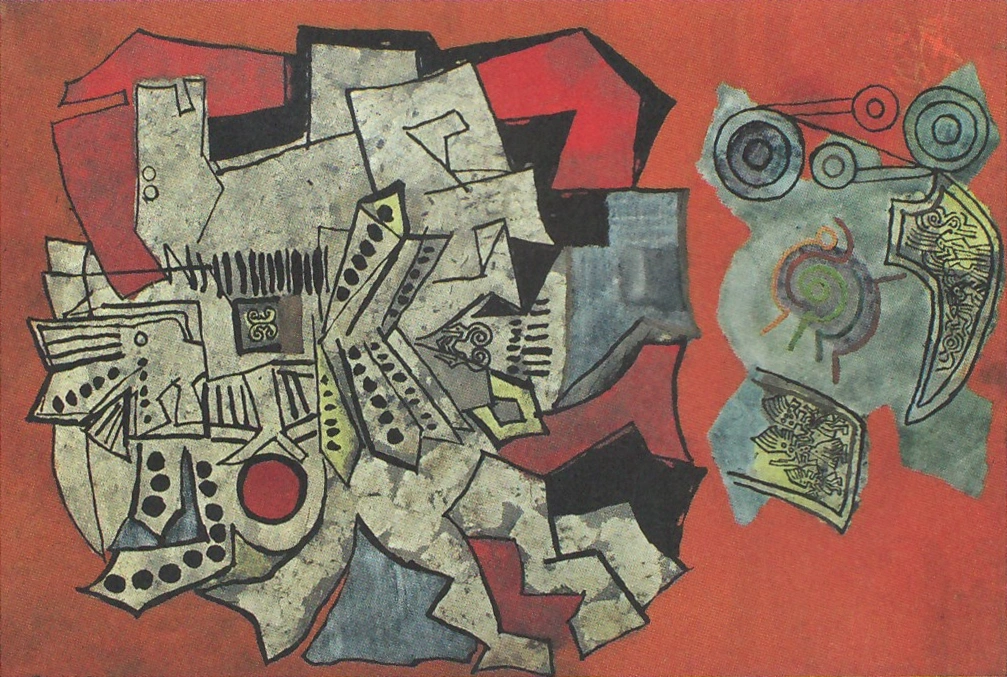

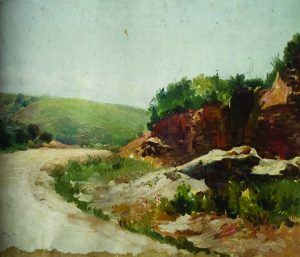

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. CIRCA 1900-1903

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

CẦN VƯƠNG PROCLAMATION

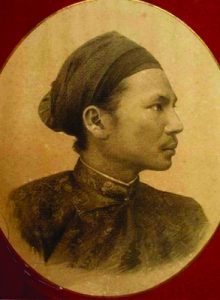

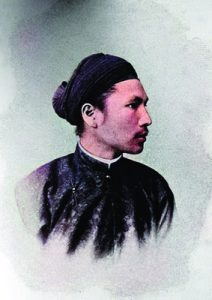

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘SELF PORTRAIT 24/7/1896’

PRINCE OF AN NAM. CIRCA 1890-1891

PHOTO BY AN ANONYMOUS AUTHOR

In 1896, under all kinds of coercion, King Hàm Nghi came to painting with the patriotism and national pride of a wise king when he made his first charcoal self-portrait. This self-portrait was drawn from a photo taken when the king had been in exile for a few years and the costume in the photo was still purely Vietnamese royal style. Afterwards, he printed a series of copies and gave these to people he met as a diplomatic card according to the customs of that time. But the main purpose was to say: “I am still the king of An Nam and the French cannot subdue the patriotism and national pride of a king like me.” This could be further confirmed through the king sending these two diplomatic cards to Indochina to General Rheinart, who was resident in An Nam and to Governor-General of Indochina Richaud, in which he signed himself and called himself “The one who fights against the French.”

One of these prints he also gave to the French sculptor and painter Auguste Rodin. Below the drawing of King Hàm Nghi was written: “To Mr. Rodin/The eternal friendship/Prince of An Nam/July 21, 1899)”. When receiving the self-portrait of King Hàm Nghi, lawyer Louis Tirman, the governor of several departments of the French Algerian Governorate, did not evaluate the aesthetic value of this painting, but he highly appreciated the courage and certainly believed that this was an action motivated by the will to resist the French of the King of An Nam.

King Hàm Nghi represented himself, the elite and the Vietnamese national spirit through the first lines in such a realistic style.

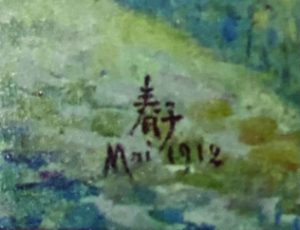

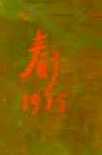

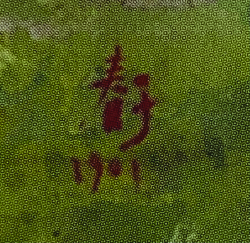

The artist interspersed very detailed parts with blurred areas to create this self-portrait and signed it in Chinese characters: Tử Xuân or Xuân Tử. In a letter to Georges Lahaye, the king wrote: “I must tell you that it is not the artist who is the enemy of pictures.”

SOME SIGNATURES IN CHINESE CHARACTERS

OF KING HÀM NGHI

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘ALGÉRIE’. 1900

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. CIRCA 1900-1903

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. 1930. OIL

PRIVATE COLLECTION

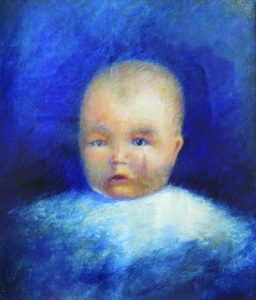

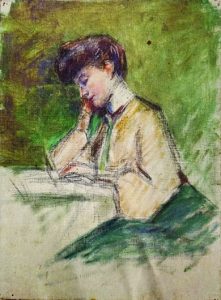

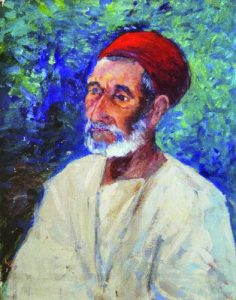

In addition to self-portraits, King Hàm Nghi also painted portraits of relatives and friends. In another letter to Lahaye on August 29, 1899, the king shared, “I have painted a lot, I even painted portraits of my friends.” As for portraits painted by the king, we only know of three representative works: A portrait of his daughter Như Mây at the age of one (1906), a portrait of his wife Marcelle (1905), and a portrait of his gardener.

In his spare time, the king also painted landscapes, although his painting techniques were still limited. To improve his skills, he studied sculpture at the workshop of Auguste Rodin and painting twice a week at the workshop of Marius Reynaud, an Orientalist painter, as well as attending lectures at the school of fine arts. Although he studied painting, the king was still under house arrest through the intermediary of the French officer Henri de Vialar. Unfortunately, the works of King Hàm Nghi in his first seven years of painting are no longer available or are unknown. He spent more time on art than politics, interacting with great French painters and intellectuals, such as Charles Gosselin, Léon Fourquet, Pierre Loti, Louis Massignon, Pierre Roche, Georges Rochegrosse, Camille Saint-Saëns, and certainly with Rodin and Reynaud… Among these figures, the close relationship with writer Judith Gautier through exchanges on literature and art was the most significant. The North African pictorial newspaper also published a picture of King Hàm Nghi talking with the world-famous Japanese painter Foujita, proving that the king still maintained a very high Asian orientation in his thinking through studying painting, interacting and discussing art with painters who were more inclined towards Asian styles.

Later, every two years, the king would go to France for three months each year to paint, and still used the original name as signed on the self-portrait, Tử Xuân or Xuân Tử. “Tử Xuân, Xuân Tử” means Son of Spring, as a hidden message of resistance and stripping him of the title “Prince of Annam” that France had given him. Poet Judith Gautier wrote a poem for her close friend with the name Tử Xuân, in which there were verses that implied the king’s spirit of resistance.

“Tử Xuân, your flowers have just bloomed

Has fallen apart in the fierce wind

Smashed, once, hope and roses

Overthrew the golden palace built of sandalwood…”

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘NHƯ MÂY’. 1906

PASTEL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘NHƯ MÂY’. 1906

PASTEL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘SAID’. CIRCA 1930

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘SAID’. CIRCA 1930

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

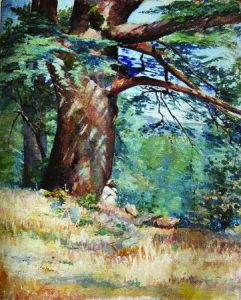

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘THE ANCIENT OLIVE TREE’. 1905

OIL ON CANVAS. PRIVATE COLLECTION

TWO NABIS-STYLE WORKS IN THE FIRST APPEARANCE

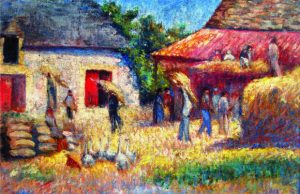

The first oil painting by King Hàm Nghi that is still preserved today is the work “Untitled”, depicting the countryside around Alger, dated May 19, 1899. From 1899 to 1903, the king delved into the techniques of the Impressionist school, with adjacent brushstrokes. During this period, the works were mainly landscape paintings. He shared to Lahaye: “I and me, who ignore almost everything, possessing only the expertise of admiring and loving the beauty of nature.” On January 2, 1896, he wrote to his friend Charles Gosselin, in which he said: “This is what I want to say: I only like the present time in African country clothes.”

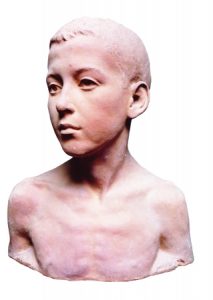

According to Amandine Debat: “[Hàm Nghi’s] Paintings have a coherent structure, selective colors, and content that seeks the beauty of nature, but is discreet, sad, and melancholy because art is a means to express nostalgia for his homeland. He created oil paintings, pastels, bronze sculptures, and plaster sculptures. While most of the painting themes were landscapes, in sculpture, the king depicted women’s or human faces through busts. He was always like a Western artist and a Vietnamese artisan.”

From 1895 to 1902, King Hàm Nghi created at least 25 oil paintings on canvas, 9 signed Xuân Tử, 2 signed Tử Xuân, of which 17 were landscape paintings. The largest painting measured 49 × 64.5 cm, the smallest measured 24 × 35 cm. However, some researchers believe that at least 45 oil paintings were made during this period when studying some works of unknown date.

Through the landscape paintings of King Hàm Nghi, we can see the Vietnamese culture through the way he handled the composition, with the position of the ancient trees standing out on the left side of the painting. This distribution is inspired by the traditional composition of Vietnamese landscapes, such as the position of the ancient trees alone in the middle of the field highlighting the presence of sacred spaces or places of worship. Amandine Dabat believes that King Hàm Nghi tried to show his connection with his homeland through the way he depicted the landscape of Algeria or mainland France according to the images he still had of Việt Nam.

One of the most outstanding works of King Hàm Nghi during this period is the painting “Landscape of Algérie”. This is the work that most clearly shows the king’s ability to express light. The midday light breaks the color of the sky and the hills in the background, it illuminates the field with a brilliant yellow, while the tree, the subject of the painting, has a contrasting light. The dark part of the tree stands out against the light background and the shadow of the foliage spread symmetrically under the tree is illuminated by the details of the flowers on the ground with white, yellow, red. The contrast between the dark part of the tree shadow and the beauty of the flowers in the foreground brings a poetic touch to this painting. A work that shows the king’s artistic qualities but still somehow evokes the loneliness and melancholy of a person exiled from the homeland.

When the artist puts characters into the painting, it often makes the painting more vivid. In the landscape paintings of King Hàm Nghi, the characters make the loneliness and melancholy even more intense. There are only two landscapes of King Hàm Nghi that have human figures. Could it be that the artist wanted to paint himself and the loneliness with him? Amandine Dabat once commented: “In the context of exile, making art created an opportunity for King Hàm Nghi to maintain his connection with Indochina, and art was a free space through which he could freely express his attachment to his homeland.”

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘JOSÉ-LALOE’. 1921

TERRACOTTA

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. CIRCA 1903

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. 1889

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

KING HÀM NGHI. ‘UNTITLED’. 1902

OIL. PRIVATE COLLECTION

There is only one architectural study made by the king. It shows the roof of a villa, with similarities to the decorative paintings of Oriental painters and in the style of Impressionism, with touches of interwoven colors.

1904 was a very special year for the king. That year, he got married, and in his painting, it is easy to see a clear change in his style. He studied to expand the color palette according to the color ranges used by Gauguin, adding bright, vibrant colors such as pink, orange, vermilion, lilac, etc. Moreover, the matte color areas (aplat) were also applied very smoothly, the constraints in the imitation of painting, the constraints of realism were significantly removed. His pastel technique was very skillful through the effects of light. In particular, the study and depiction of the sky and its shades inspired the king. In a letter to his daughter, he wrote: “Sunset, a magnificent sky, yellow, red, green, lilac, orange; a fire from heaven…”

On October 31 (1904), the Petit Palais dedicated a gallery to him; in November, Ambroise Vollard also organized an exhibition for him. But it was not until December 6, at the Salon d’Automne, that the king’s two “aplat” landscapes in the Nabis style were presented for the first time. These experiments went beyond the purely academic style of art education. While the Nabis Group focused on painting urban life or studying human figures, King Hàm Nghi almost exclusively painted landscapes in this style. “In exile, […] art was like a free space, where the king could freely express his feelings of attachment to his homeland.”

By 1915, a number of Post-Impressionist paintings had been made by the king, with a very unique blue.

From 1916 to 1926, his paintings gradually moved towards abstraction. Through the painting “The pine”, we can somewhat feel this tendency.

According to Amandine Dabat, the king did not paint for others but for himself. Therefore, King Hàm Nghi’s artistic views had very unique features, even though he was influenced by Gauguin, Nabis, Impressionist or Post-Impressionist movements at times. For King Hàm Nghi, painting was not only a free space, but also something very personal that he could freely practice in his private life without having to worry. Art was a bridge for him to express his attachment to the homeland Việt Nam. Another interesting thing is that he mainly painted landscapes, a few portraits, a few sailors, but absolutely not political themes.

TWO DAUGHTERS NHƯ LÝ AND NHƯ MÂY

IN THE STUDIO OF THE FATHER, 1915

KING HÀM NGHI IN HIS STUDIO, 1935

THE WEDDING OF KING HÀM NGHI AND

MS MARCELLE LALOE, 1904

King Hàm Nghi was a victim of political events, he always yearned for freedom, and he sought freedom for his soul in his own way. Art, more precisely painting and sculpture, opened up that horizon of freedom. “These are very wonderful and fascinating arts, bringing indescribable joy. I can tell you: There is nothing more beautiful than lines and composition. But to appreciate this kind of beauty, one must live to fully appreciate the art of painting.” (Letter to his friend Georges Lahaye, May 10, 1903).

During his exile, King Hàm Nghi spent most of his time painting and sculpting and never told anyone about his days of resistance during Cần Vương period or the secrets of his thoughts. A fire that occurred in the 1960s burned all of his Chinese characters writings. Therefore, the inner life of a patriotic king who came to art with a spirit of national pride remains a mystery, a mystery that any Vietnamese person, when mentioned, clearly shows admiration.

WRITTEN BY NHÃ KHAI

SOURCE: FINE ARTS MAGAZINE