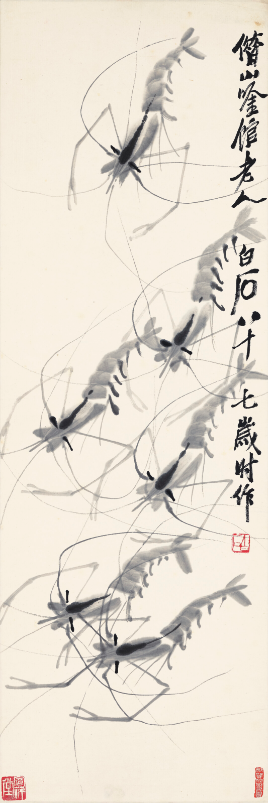

1. Qi Baishi (1863-1957)

The work of the great Chinese master Qi Baishi had a profound and underappreciated influence on Picasso. Qi Baishi’s lively, energetic painting directly inspired some 200 sketches across a number of Picasso’s sketchbooks, in which brush and Indian ink were employed in a distinctly Chinese style.

The freedom and precision in Qi Baishi’s brushwork was an inspiration to Picasso, who also discovered in Chinese painting an empathetic way of representing the world — much preferred to the strict realism of traditional Western painting. Later in life, he would describe the impulse behind Cubism in these terms: ‘We were realists, but in the sense of the Chinese saying, “I do not imitate nature, I work like her”.’

Qi Baishi. Shrimps.

Qi Baishi. Insects and leaves.

2. Zhang Daqian (1899-1983)

Picasso’s appreciation for Chinese art might have remained a secret were it not for the famous and remarkable visit of Zhang Daqian to Picasso’s studio and home, the villa La Californie, near Cannes, on 28 July 1956. After two successful exhibitions in Paris, Zhang Daqian wrote to Picasso and suggested a meeting, recorded and recounted in a teasingly laconic way in Zhang Daqian’s memoirs.

The two artists spent several hours deep in discussion about Chinese art, and Zhang Daqian was surprised to find that Picasso was familiar with traditional Chinese painting. The two men then exchanged gifts. Zhang presented Picasso with six brushes, his exhibition catalogues, and a number of reproductions of Zhang’s personal collection. Picasso gave Zhang and his wife a number of sketches, including some painted with Zhang’s brushes.

The photographs of this historic meeting capture a rare moment in which contact was made between two great and innovative artists from the East and the West. It was not just a case of one-way influence because although Zhang Daqian was adamant that his technique derived solely from Chinese painting history, his painting style clearly shows he was influenced by a number of sources.

Zhang Daqian. Splashed-colour Lotus.

Zhang Daqian. Landscape in Splashed Colour.

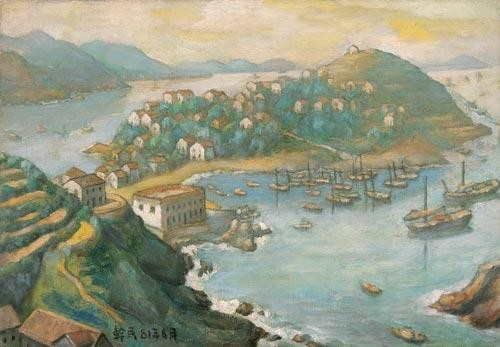

3. Lin Fengmian (1900-1991)

In 1918 Lin Fengmian moved to Shanghai, where he saw an advert for a work-study programme in France. By the winter he was working in France as a signboard painter, entering the Dijon Academy of Fine Arts in 1920 as one of the first wave of Chinese artists to spend their crucial early years in Europe.

Within six months he was recommended to the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, studying classical Western works in the Louvre and Modernist painting in Parisian galleries, before returning to China in 1925 to found the National Academy of Art (now China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou.

A pioneer of blending Eastern and Western styles of painting, in 1951 he attended the Beijing national opera, seeing in it material for his famous Beijing Opera series. He commented: ‘In the old plays, there’s a better resolution of the conflicts between time and space, like in Picasso, when he handles objects by folding them into a flat space. My goal is not to show these figures and objects massed together but to show an overall sense of continuity.’

Lin Fengmian. Birds with Autumn Leaves.

Lin Fengmian. Fishing village.

4. Fang Ganmin (1906-1984)

Fang Ganmin left China at the age of 20 to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. In doing so he was following in the footsteps of artists such Pan Yuliang, Xu Beihong and Sanyu.

When he returned to China in 1929, he took up a position at Lin Fengmian’s newly-founded National Academy of Art in Hangzhou. There he taught Western art, concentrating on the female nude painted in a style reminiscent of Cubism and works by Picasso he had seen in Paris. Because of his art and his family name — ‘Fang’ is Chinese for ‘cube’ — his students nicknamed him ‘Cubist’.

The National Academy in the 1930s was a hotbed of intellectual and painterly innovation, with traditional painting under Huang Binhong and a Western art department comprising Lin Fengmian, Fang Ganmin and Wu Dayu. Among the students were Zao Wou-Ki, Chu Teh-Chun and Wu Guanzhong.

Fang Ganmin. Landscape of Zhejiang.

5. Zao Wou-Ki (1920-2013)

Throughout his education at the National Academy of Art, Zao Wou-Ki was drawn towards a more Western style of painting, encouraged by his revolutionary teachers. His first exhibition in 1942 was a two-man show alongside his teacher Wu Dayu. Based on postcards sent from Paris by his uncle and reproductions seen in the American magazines such as Life, Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, Zao Wou-Ki exhibited a series of incredible drawings influenced by artists such as Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso.

Wishing to see these great Western works in the flesh, Zao Wou-Ki moved to Montparnasse, Paris, in 1948, living near Giacometti’s studio on the rue Hippolyte-Maindron. Within three years his work was being shown at Galerie Pierre, and winning the admiration of Joan Miró and Picasso himself.

By the time of his death in 2013, Zao Wou-Ki was one of the most significant Chinese painters of the 20th century, bridging the gap between East and West.

Zao Wou-Ki. 24.12.59.

Zao Wou-Ki. 29.09.64.

Source: Christie’s, Invaluable.