In the midst of the City of Light today, to escape the bustle, people seek out the largest green space of the city, Bois de Vincennes, located on the eastern edge of Paris, in the 12th arrondissement. It is hard to imagine that in this forest, around Daumesnil lake, there was once a ‘city of colonies’ with dozens of massive architectural models in the cultural style of each colony, dozens of villages crowded with the presence of thousands of indigenous people from French colonies around the world, including Annamese musicians, African artisans, Arab knights, and even cannibalistic Kanak natives, etc. There were once five countries in Indochina with the Angkor Wat temple recreated in a 1:1 scale, houses and temples with the architectural style of the three regions of Việt Nam. This was the site of the International Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1931 (an exhibition area of 1,200m wide and more than 10km long), which lasted for six months and attracted more than thirty million visitors. It was a spectacular sight marking the pinnacle of the French Empire abroad that it wanted to promote and glorify, as in the speech at the inauguration of the Minister of Colonies Paul Reynaud, the essential purpose of this exhibition was to make the French aware of their empire. It must be recognized that this exhibition had a strong ethnographic and cultural and artistic museum character that the French always paid much attention to, ironically it was also the brilliant halo at the sunset of the Great French Empire (la plus grand France), between the two world wars, before collapsing under the colonial liberation movements.

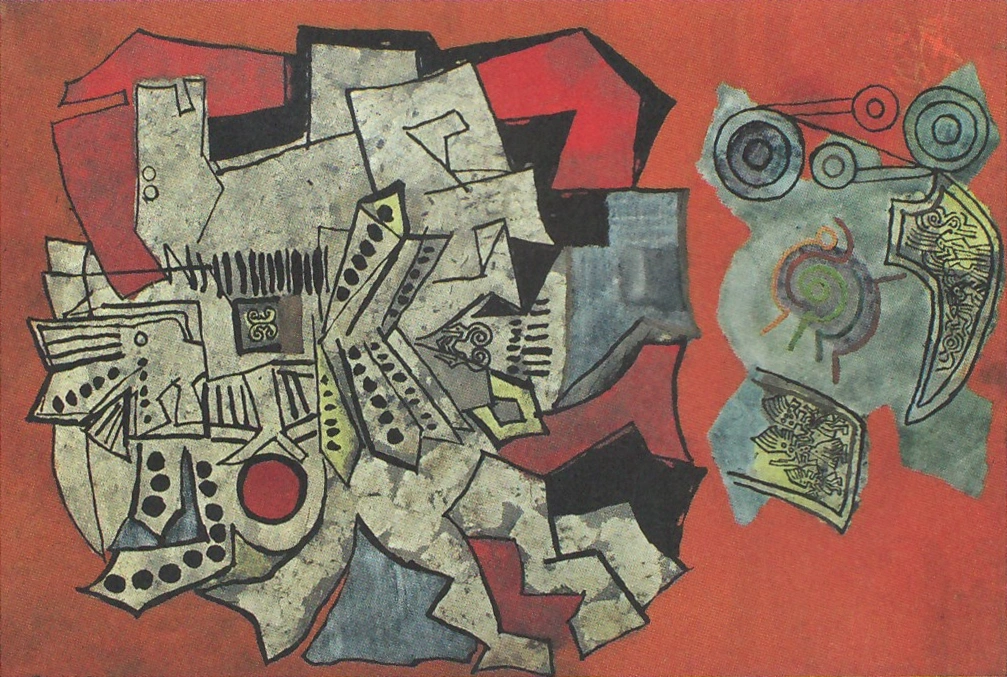

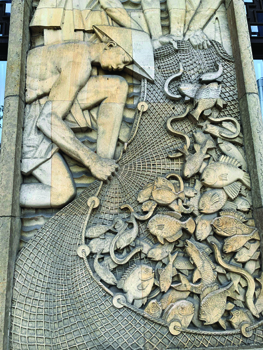

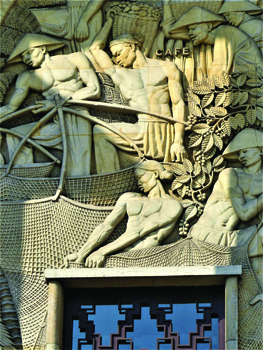

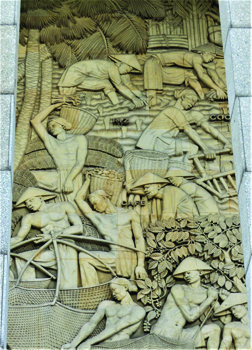

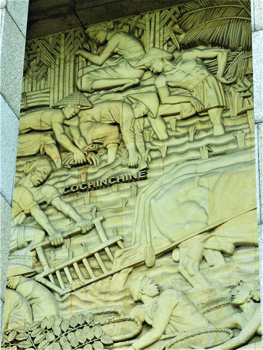

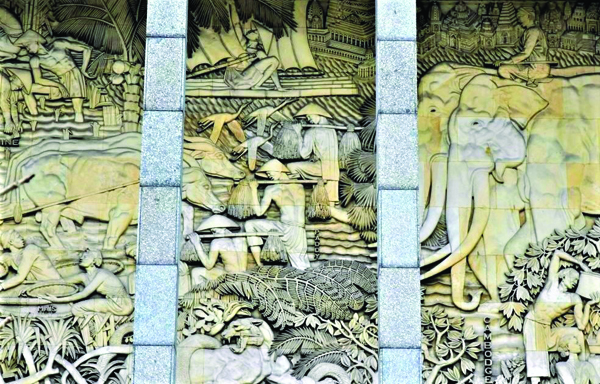

Detail of the relief on the right of Palais de Porte Dorée’s facade

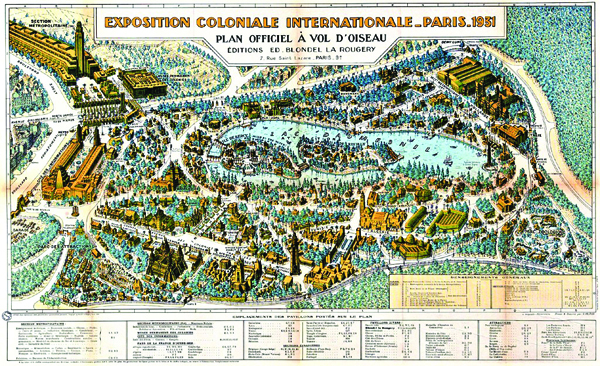

Map of the International Colonial Exhibition-Paris-1931; lower left is the

Indochina area; the Colonial Museum is on the lower right edge

At the entrance to the Vincennes Bois, which has a special tropical garden that still preserves traces of the Indochina village of the world exhibitions from a bright time of Belle époque to the 20th century, we will first see an important remaining witness of the 1931 Exhibition, the Palais de la Porte Dorée (Golden Gate Palace), formerly the Colonial Museum (Musée des Colonies) designed to be a lasting work, a hymn to the French Empire at its peak.

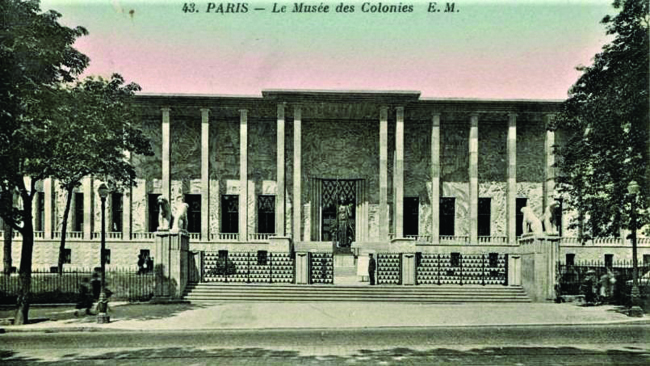

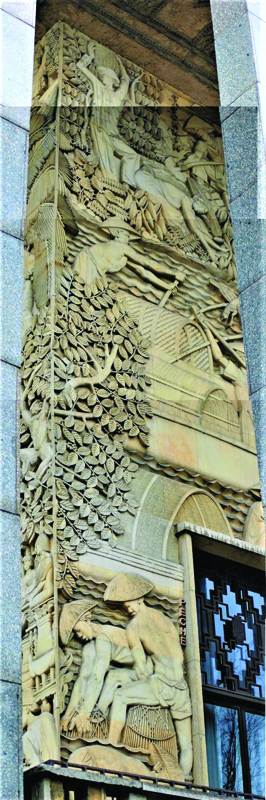

Among the approximately 150 museums of Paris, the Palais de la Porte Dorée – in terms of architecture, decoration, sculpture and reliefs – is a remarkable exception, a masterpiece representing the golden age of Art Déco, well worth admiring and contemplating. The facade of the building is a giant relief carved entirely in stone, whose size and scale surpass all the achievements of the art of relief in Europe or the whole modern world, called the ‘stone tapestry’ (tapisserie de pierre) covering a surface of 1130m2 – 12m high and 92m long, a size that can only be compared with the great carvings on the walls of the temples of Egypt, Assyria or Angkor Wat. The stone slab to the left of the entrance is engraved: ‘This relief was created, painted and sculpted by Alfred Janniot between 1928 and 1931. Gabriel Forestier and Charles Barberis collaborated on the work.’

Colonial Museum in 1931, designed by architect Albert Laprade,

the relief of the façade decorated by Alfred Janniot

Palais de la Porte Dorée is a fusion of contemporary Art Deco architecture, classical French

architecture with elements inspired by arts of the colonies

With the process of three years, Janniot’s work shows the laborious stages of conception and execution, with extraordinary energy, a creative imagination based on the absorption and synthesis of all the major sculptural styles of the past (such as Egyptian, Greco-Roman, Assyrian, Angkor-Bayon) as well as ethnographic references and knowledge of natural sciences in exotic colonial regions. On this ‘stone tapestry’, expressed in bas-relief, Janniot captures the cultural characteristics of 28 colonies, with their racial characteristics, costumes, and all working hard in the natural landscape. When contemplating the entire relief with more than 200 species of animals and plants represented, we can think of making a systematic list of the animals, plants and certainly the anthropological characteristics that appear; it is like a magnificent picture book representing the colonies carved by the magical hands of a master, although the ‘mission’ is aimed at propaganda by glorifying the labor of the colonial nations who are contributing to ‘Mother France’.

After the French colonies regained independence, the Colonial Museum experienced complex ups and downs in many name changes, such as the later change to the Museum of African and Oceanic Arts, until in 2003 its collections were transferred to the new museum Musée du Quai Branly, and in 2007 the Palais de la Porte Dorée became the Museum of the History of Immigration and the Tropical Aquarium.

After the French colonies regained independence, the Colonial Museum underwent complex ups and downs in changing its name several times, later becoming the Museum of African and Oceanic Arts, until in 2003 its collections were transferred to the new museum, the Musée du Quai Branly, and in 2007 the Palais de la Porte Dorée became the Museum of the History of Immigration and the Tropical Aquarium.

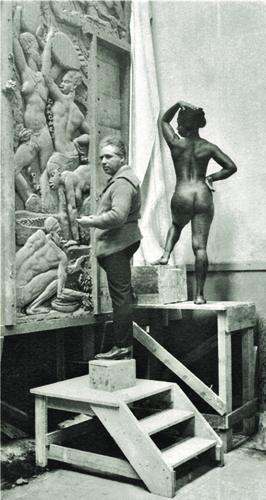

Sculptor Alfred Janniot (standing on the left) and colleagues making

the Indochina relief for the façade of Colonial Museum

Janniot and the model for the African relief

Before taking a look at Janniot’s relief on the facade of the Colonial Museum, we should list some other large-scale works of the genre related to the theme of Indochina (in whole or in part) that are present in this unprecedented exhibition:

– Large frescoes with a total area of 600m2 by Ducos de la Haille (1889-1972) decorate the halls of the Colonial Museum, with the theme ‘France and the Five Continents’ about the French contribution to the colonies (to counterbalance Janniot’s external relief on the contributions of the colonies to France), including large ones depicting the spread of medicine and science in Indochina in the ‘civilizing mission’.

– Georges-Michel (1883-1985) with five large oil paintings on canvas, 50 m2 in area, decorated the Colonial Museum, depicting the colonial peoples exploiting the main products for export to France from plant, animal, and mineral resources.

– André Herviaut (1884-1969) painted three large paintings for the Colonial Museum depicting the role of French officials in the colony, including surveyors, construction engineers and administrators.

– The artist Boullard-Deve (1890-1970) with a monumental mural measuring 40 m long and 1.5 m high (painted with gouache on paper and mounted on canvas) depicting the ethnic communities in Indochina, decorated the corridor in a model of the Angkor Temple.

The reliefs on the right side of the Palais de Porte Dorée facade mainly depict the colonies of the Indochina Federation,

in geographical order: Cochinchina, Cambodia, Laos, then turning the corner at

the east wall to Annam and Tonkin. Between the high windows below there are a total of

10 large panels depicting agricultural, fishing and handicraft occupations, which can be

seen as standing alone while still being in harmony with the rest above.

The reliefs on the left side of the facade depict the African colonies

– Naval artist Charles Fouqueray (1869-1956) with 12 large paintings depicting ports in the colonies, including Hải Phòng, Sài Gòn, Đà Nẵng.

– A set of 84 reliefs by Emile Pinchon (1872-1932) covering nearly 500m2 of decorative surface for the galleries in the massive building called La Cité des Informations. This was Pinchon’s last monumental achievement depicting scenes of life and work in the colonies. Unfortunately, like the fate of other decorative works destroyed after the exhibition (including three reliefs by students of Indochina Fine Arts College), only four of his works were saved, including two about Indochina with agricultural and industrial themes, currently hanging in an office of the Noyon City Hall.

– And we must mention the set of reliefs made by three students of Indochina Fine Arts College to decorate the main hall of the Indochina Palace, including three pieces, totaling 39m long, 2m high, with three themes: Agriculture by Vũ Cao Đàm, Fishery by Georges Khánh, and Industry and Commerce by Lê Tiến Phúc. The year 1931 was also a highlight marking the first class of artists graduating from Indochina Fine Arts College to attend this first international exhibition in Paris, some of them also came to decorate the Indochina booths, with the teacher and principal of the college, Victor Tardieu, as curator of the Indochina exhibition booth, at that time he had just completed a 77m2 mural for the lecture hall of Indochina University in 1928.

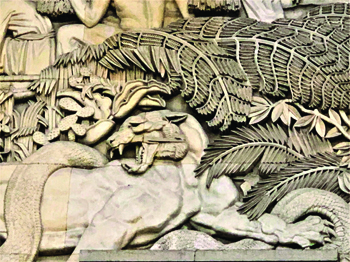

Details of the relief

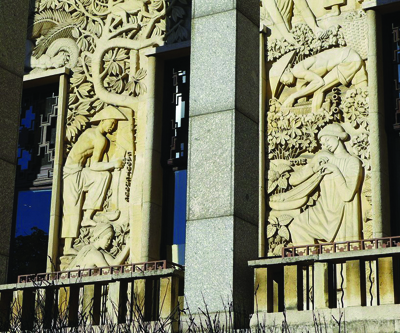

Janniot’s relief work can be viewed as a visual catalogue of imposing proportions, although it is part of a wider decorative arts program that includes sculpture by Léon Drivier, interior murals by Ducos de la Haille, and interior decoration by several major French designers, under the direction of the architects Albert Laprade and Léon Jaussely. Each artist plays a role in the overall message of the building. But Janniot’s immense contribution dwarfs the others. Of the four types of relief carving, Janniot chose to use the first, the bas-relief, which was revived in the 20th century to decorate large architectural works in the prevailing Art Deco style, and which also borrowed from ancient relief art in architecture.

However, the relief is largely hidden from view, as its all-encompassing relationship to the building makes it difficult to see the larger picture. The French colonial territories stretching from the Caribbean through Africa and Asia to the South Pacific cannot be seen without walking around the building, so only parts can be seen from any angle; photography, too, does not capture a wide view but only sections viewed from below. The surrounding relief is divided into three sections (the façade and the east and west walls). Twenty-two windows further break up the composition at the bottom, each reaching up to four meters from the floor. Any distant view is blocked by the stone columns that connect the overhanging porch, as is the railing that rises above the porch. Therefore, to grasp the whole picture in one’s mind, one needs to walk along the museum porch, to the east or west while looking up at the relief wall to see the details, and then back down to the ground, looking from the street or from the entrance to understand this stone tapestry both vertically and horizontally, from which one can grasp the full breadth of Janniot’s vision.

Details of the relief

Of the 28 French colonies in the world described and named on this ‘stone encyclopedia’, the two important elements that are vividly described are the African and Indochina colonies. Let us take a look at five elements of Indochina: Cochinchine, Cambodia, Laos, Annam, and Tonkin.

When stepping on the main entrance steps before entering the Museum, the central axis on the threshold is the tympanum for all to converge, France as we often see is symbolized by a woman, on one side is the word La Paix (Peace) and on the other side is Liberte (Freedom), but here is a goddess symbolizing abundance with a large body, behind the goddess is a bull sitting on the ocean with girls converging around such as Ceres – goddess of agriculture, Pomone – goddess of fruits, and surrounding the two sides of the door are the names of French ports where products from overseas or colonies are transported to such as Bordeaux, Garonne river, Le Havre in the west, and below Paris airport is Marseille and the Mediterranean on the east, along with the architecture of citadels and towers. Starting with this central symbol, the colonies are on both sides, according to geographical logic and symmetry.

We need to take a look at the ‘map’ layout of this relief. From the steps leading up to the main entrance with the tympanum just described, if we go along the porch to the left, we pass through North Africa, from Tunisia to Algeria along the top of the facade, and from the Congo to West Africa and then up to the northwest to the Niger River basin, then Morocco, Senegal… At the lower edge is East Africa – Reunion Island and Madagascar. And when we turn the corner of the building, we pass to the islands of the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean and the Americas. Now we go back, through the main entrance to see the relief of Asia on the right wing or east wing of the building. Before reaching Indochina, we see on the top of the pediment, a woman sitting on the deck of a sailing ship, her head wrapped in a flowing scarf, her face turned in profile towards France. Her dress and the palaces rising behind her are the French trading ports in India. Just below the ship on which she is sitting, an airplane appears out of the clouds.

Now we move on to Indochina with the relief layout following the geography from south to north. Below are descriptions or annotations of the images on the relief for readers to enjoy.

Details of the relief

On the first panel below, the sea continues but it is an underwater ecological scene, and a flock of seagulls flying. Under the tropical Pacific seabed we see various marine creatures and plants. Above is a row of coconut trees intertwined and spreading behind the next window, and above is the coast, behind the three-masted sailing ship on the shore, we see a more modern steam-powered transport ship.

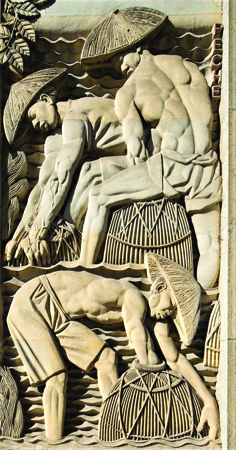

The coconut trees connect to the next panel, we see an impressive scene below, in the middle of a large net is full of fish, eels, loach, crabs… looking up, there are three fishermen pulling in, the person in front looks down at the net. Above we see a series of nets on the river that a fisherman is releasing. And the large net continues to the window and the next panel has three more fishermen pulling hard, at the bottom, there are also two bare-chested fishermen, heads wrapped in scarves and wearing sampot loincloths, they seem to be talking to each other while pulling a smaller fishing net. Through these vivid scenes, we see that Janniot paid special attention to describing fishing in Indochina, which we will see in turn with the methods and tools used to fish, such as large nets for seafarers, small nets, nets or cast nets on rivers, or using traps in shallow waters, and especially described in detail the fish and aquatic species typical of Vietnamese sea.

Behind the fishermen are coffee trees, the word CAFÉ appears between them. A group of porters are carrying baskets of products, and there are three farmers sowing in the rice fields while the fourth is supervising. In the foreground, a farmer is pushing a plow with two buffaloes, and below, the word MAIS (corn) is engraved, men and women are sifting the corn. At the top, a woman is cutting bamboo. COCHINCHINE (South Vietnam) is engraved in the space of a rice field, this is the southern region at the estuary of Mekong River.

In the isolated forest, a fierce battle takes place between two beasts, a large reticulated python is entwined with a muscular Indochinese tiger. The spectacular scene shows the power in the natural wild world of the tropical forest with a terrifying beauty. Looking up, behind the dense bushes like cacti and ferns with the tiger’s head growling, we see three men carrying bundles of rice, the field they pass by is engraved with the word PADDY (rice field). Behind them, a flock of storks flap their wings, in the distance, a woman is rowing a raft up the northern side of the Mekong towards the Tonlé Sap Lake. Far behind the sail of the raft we see the temples of Angkor Wat.

Details of the relief

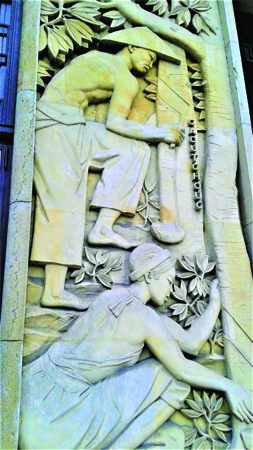

Below the scene of wild animals fighting across the next window is a peaceful scene, POIVRE (pepper), a man and his wife in long dresses, wearing scarves, with their son standing in front of the vines and collecting peppercorns into a bamboo basket.

Looking down again at the panel between the next two windows is a scene of latex harvesters in a plantation, we see a woman bending down to collect latex in a bowl. On the tree is the word CAOUTCHOUC (rubber), a man is using a knife to scrape the thin bark on the trunk to let the latex flow.

Above the trunk of a rubber tree is a monkey climbing up, we see the name CAMBODGE, next we see the scene of latex harvesting, under the canopy of the rubber tree we see three plantation workers with Khmer scarves on their heads, they seem to be chatting while collecting and pouring latex into a tank to wait for processing. Two Asian elephants with a mahout walk towards the main entrance, showing an accurate depiction of the elephant’s features and form, mirroring the movement of African elephants on the west wing. The Angkor temple complex spreads out behind.

On the next panel, a woman and a man are harvesting cotton, COTON (cotton yarn). Below, in a mulberry bush, a silk reeler gently pulls and weaves silk threads from silkworm cocoons that have shed their silk, next to a silkworm pupa lying on a mulberry leaf with the word SOIE (silk).

Looking up above the elephants, we also see a flock of storks flying over the river. On a flooded rice field, another group of farmers are planting rice, engraved with the word RIZ (rice), and a large bamboo irrigation wheel is bringing water into the field, engraved with the name LAOS (Laos).

Details of the relief

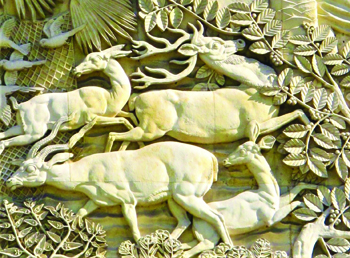

Behind the two Asian elephants, under the palmyra palm tree, we see a man throwing a net, a flock of birds flying in all directions, in the net there are kinds of birds, mainly Indochinese parrots, some big, some small, some with short tails, some with long tails. In front of the man is a herd of deer running in panic in various lively postures. They are deer species endemic to Indochina, we see four of them: muntjac, musk deer, yellow deer with large antlers, and an antelope with curved horns leaning its head and walking towards the white pheasant with a large and long tail under the cinnamon tree.

Above the herd of deer, under the coconut tree, HUILE (oil), a woman is reaching out to pick coconuts, opposite is a man next to a jar, he is holding a ladle to scoop and pour the coconut cream into a vat to process coconut oil.

The panel below the long-tailed white pheasant, next to the tea bushes, is engraved with the word THÉ (tea), a man is spreading leaves in a tray, a girl is placing the tray on a drying rack, and another girl is holding a tea pot.

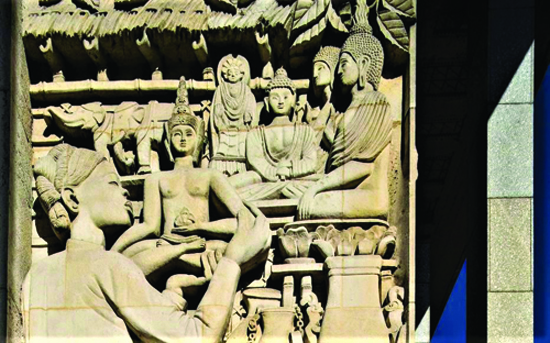

The relief in the back corner of the museum, under the bamboo roof, we find the only representative of the handicraft industry, in a workshop carving all kinds of Indochinese Buddhist statues, elephant statues, and ceramic vases on shelves, and bronze objects such as incense burners. An artisan is placing a finished Buddha statue on a shelf, under his arm is the word ARTS (fine arts). A second artisan is busy carving a wooden statue of a mandarin. Surely the sculptor Janniot was very interested in describing the famous carving skills of the Indochinese artisans whose products are always displayed in international exhibitions in France.

Details of the relief

Before turning the corner, we see a coconut tree and a coffee tree with a monkey swinging from branch to branch to continue to the east wall on which is engraved the name of ANNAM (Central in Việt Nam), we are on the central coast, with covered boats, the word PÊCHE (fishing) engraved under the side of the boat, and we see on the panel below three men wading into the pond using traditional fishing gear, a trap to catch fish, shrimp and crabs. The man in front finds a fish struggling and puts his hand through the mouth of the trap. All the postures and sinewy muscles on their bodies are carved very delicately compared to the depiction of fishermen in the first two panels on the front. And if we continue to the last panel about Indochina, there is also another group of fishermen calling each other and pulling a net full of aquatic products.

Along the central coast up to the Gulf of Tonkin, we see fishermen rowing and placing lifting nets or frame nets right in front of the boat’s bow or side.

Above, we see some more coffee trees, coconut palms and betel vines, with the man at the top carrying a basket facing two others also carrying baskets around the corner. On the right is engraved CHARBON (coal), a coal miner digging with a shovel, banana laden with bunches behind the miner. The name TONKIN is engraved above the coal ore. A woman wearing a conical hat is busy digging for tubers or picking plants growing in shallow water. Cormorants fly in front of the bows of boats casting nets, the words MER DE CHINE (Gulf of Tonkin). Looking out to sea, there is a sailing ship going in the opposite direction. A compass symbol marks 70° LAT SUD (70° South latitude) in the foreground, corresponding to the distance of the South Pacific. From here, the remaining geography of the relief begins to describe the remaining French colonial islands such as Caledonie Nouvelle, Tahiti…

Details of the relief

Conclusion

We have briefly looked at some of Janniot’s bas-reliefs of Indochina that he decorated on the facade of a building that is one of the world’s masterpieces of Art Deco architecture. It is remarkable that Janniot did not show any French presence in these colonies other than some symbols and metaphors of France on the main door as is common in neoclassicism. By separating the indigenous workers and their production from European culture, the whole tapestry shows us that in this world, the French do not exist. Yet the ideal composite portrait of a ‘Great France’ cannot exist without the colonial people, here engaged in labor producing goods to feed French industry. Although this expression may have originated from the colonial ideology of a world of the previous century, it is not so different from today’s global economic era for developing countries in the post-colonial period.

The strangely exotic expressions that we know throughout the colonial period, from the late 19th century to the 20th century, artists were passionately looking for the sources of ‘primitivism’ art as a return to the source, where the new energy for regeneration was absorbed from the ‘paradise’ lands in the colonies such as Indochina or Southeast Asia, as well as Africa and the South Pacific islands, thereby creating a radical change in the formation of modernism right in the center of world art in Paris. That is the paradox of advanced industrial civilization.

But what the Palais de la Porte Dorée or the Colonial Museum ultimately left behind as its legacy was not the pinnacle of past economic and political power, but the accumulated surplus of exotic cultural and artistic values, and even the cultural appropriation that, when an empire reaches its peak of glory, it ‘exhibits’ these before the world. Alfred Janniot’s magnificent tapestry is a monument, a ‘tour de force’ (achievement) marking this crystalline peak, but what remains and endures over time is its tragic beauty.

WRITTEN BY HÀ VŨ TRỌNG

SOURCE: FINE ART MAGAZINE OF VIETNAM