I return to silk painting, an art form that has come hand in hand with lacquer. The king had a silk weaving workshop in Nghi Tàm, which was supervised by the princesses. According to historical records, our silk weaving craft had developed quite well since the Lý Dynasty. People used silk to pay taxes, the king used silk as salary, and paid tribute to the outside world. During the Lý Dynasty, the king sent brocade to China. During the Lê Dynasty, people were loom weavers, weaving silk for clothing and home decoration. Silk was both beautiful and durable, so many families painted portraits of famous mandarins and generals on silk for worship. Many pagodas painted pictures on silk telling Buddhist stories such as: Thích ca, Quan Âm, La hán, Bồ tát, Thập điện… Lý and Trần Kings both commissioned artisans to paint pictures of Confucian scholars who had contributed to consolidating the feudal system to worship at Quốc Tử Giám in the years 1070 and 1253. Trần Nhân Tông and Trần Minh Tông both gave portraits, or painted portraits, or painted portraits in books for loyal mandarins and righteous men who had contributed to the country against the Mongol invaders. For example, Retired Emperor Trần Nghệ Tông gave the painting of Tứ phụ to Hồ Quí Ly (1394) with the intention of advising Hồ Quý Ly to help the young Trần king, just as loyal mandarins in the past had helped the young king.

Portrait of Nguyễn Trãi kept in National Museum of History

Source: baotanglichsu.vn

Regarding the old silk paintings that have been preserved, we still have the portrait of Nguyễn Trãi, the portrait of Phùng Khắc Khoan, the portrait of Quang Trung (painted in China), the portraits of four famous scholars of the Phan Huy family through four successive generations: Phan Huy Cẩn, Phan Huy Ích, Phan Huy Thục, Phan Huy Vinh, the portrait of Nguyễn Văn Siêu, the portraits of military officers guarding Hà Nội citadel. Some other paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts have been recently collected: Return with glory, Receive ambassadors of other countries. In addition, there are some altar paintings, and paintings of birds and flowers in private houses. The original portraits of famous people in the past are often lost. Some remaining copies are just copies of old copies. But from here, I see two different painting styles. The portrait of Nguyễn Trãi is drawn in stylized lines, with delicate colors and skillful harmony, many curves are calculated according to a certain formula. The colors are absorbed into the silk, the technique is smooth. This style tends to be decorative, like the stylized dragons, phoenixes, flowers and animals at Đậu Pagoda (Thường Tín, Hà-Sơn-Bình). The portrait of Phùng Khắc Khoan is painted on large silk (about 150 × 250 cm). This style is completely different. The lines are strong, realistic, the dark-skinned face resembles the demeanor of Trạng Bùng [Phùng Khắc Khoan] as told by his descendants. The colors are rustic, thick and soft, natural according to the requirements of reality. Using vermilion, Chinese ink, and mollusks’ shell. The mollusks’ shell appear sparse and comfortable as if not intended to show off the style. This is a Vietnamese folk style close to the painting style of strong and simple peasant craftsmen who have little contact with outside techniques. The lines on Trạng Bùng’s portrait go hand in hand with the wood carvings at Tây Đằng communal house, Tây Phương pagoda, and Thầy pagoda.

Thus, I see that ancient silk painting does not have only one style. It can be said that each locality, each guild, each historical period has its own style of artistic creation based on the common features of national traditions.

French imperialism invaded our country with the label of civilization, but in fact it robbed our nation of its traditional cultural assets. Despite their intention of “civilizing”, the traditional culture of Indochina’s people conquered them in terms of artistic value. Western art turned to the East through Africa and the Near East. Since the 19th century, African statues and masks, Persian carpets, and Japanese woodblock prints were novel discoveries that were completely different from European academic art which is cliché lately. The new generation of artists sought inspiration and found fresh springs in the genres of Oriental folk art. They lacked the youthful, primitive beauty of the past, as they lacked silk, spices, pepper, and aromatics such as musk, agarwood, and rubber today.

In Hà Nội, in the early years of the 20th century, French antique and painting dealers such as Passignat, La Perle, Arquin, etc. went hunting for antiques, bronzes, ceramics, silk paintings, and ancient statues to sell or resell to the capitalist companies such as Ogliastro (Germany) and Shell (USA) for export, mainly to France, the US, and Germany. They often bought silk paintings and watercolors with strange oriental tastes. They needed paintings with national characteristics or the bustling and green landscapes of faraway humid tropics. At the same time, they tried hard to research Indochina art, including Đông Sơn, Chams, and Khmer art, which brought fame and money to some scholars, academic institutes, and dealers. Here they could find something newer, refreshing the drying up of the Greek-Roman stream.

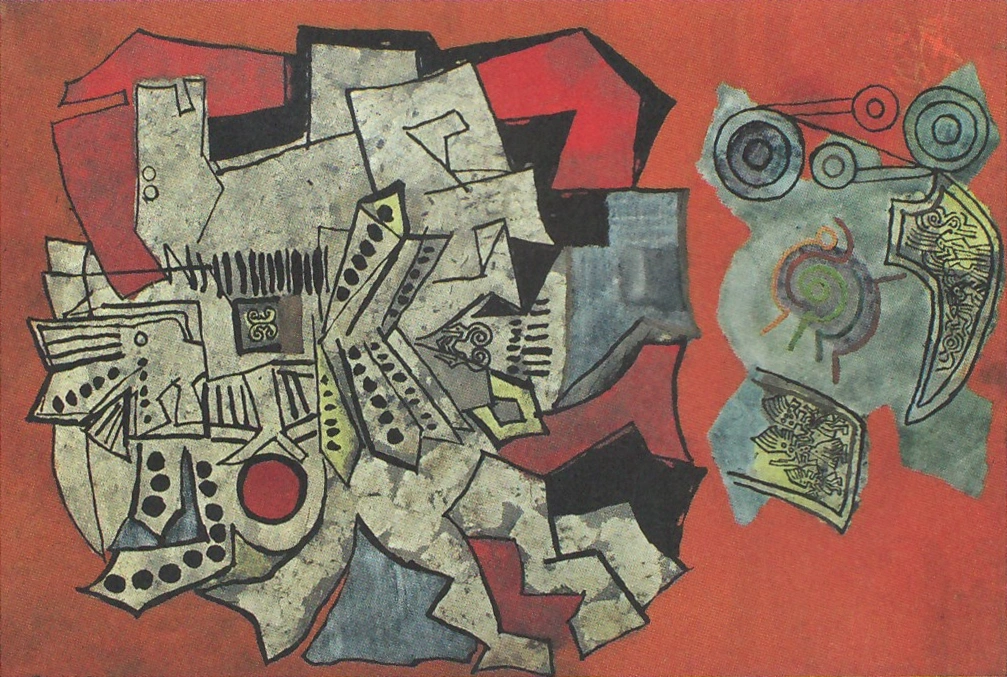

NGUYỄN PHAN CHÁNH (1892-1984). ‘The busker’. 1929. Silk

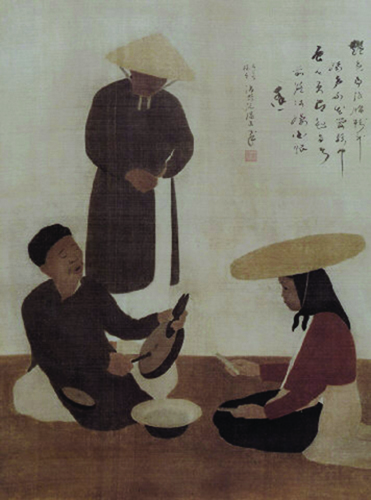

NGUYỄN VĂN ANH (1914-2000). ‘Reading’. 1937

Silk. 62 × 38 cm. Foreign private collection

In such a cultural and artistic movement, at the colonial exhibition in Paris – 1931, Vietnamese silk paintings were introduced to the European public. Vietnamese painting art far exceeded the wishes of the French colonialists. Along with ancient bronze art and folk woodblock prints in exhibitions from the end of the 19th century, the European public knew about the art of painting in Việt Nam through silk paintings with modern works by Nguyễn Phan Chánh, Thang Trần Phềnh, Nguyễn Nam Sơn, Tô Ngọc Vân. In the years 1928-1929, Nguyễn Phan Chánh began to study silk painting. The painting style of the above painters was based on European realistic techniques of form but still maintained the compositional style, brushwork and oriental color harmony, taking the daily life and landscape of the country as the subject of their work.

If we only look at the paintings based on their themes, we cannot fully appreciate the artistic value of the first silk works of the modern period before the August Revolution: Meal, The young lady washing dishes, The busker, The young woman sewing (1929-1931), Spirit transmigration, Washing vegetables by the pond, A child feeding the birds, Washing rice, Playing Ô Ăn Quan (1932) by Nguyễn Phan Chánh; Coming back from the market (1927), The woman with a white scarf (1930), Spring sight seeing, A father advises his son, Buying and selling rice on Hồng river bank (1931-1933) by Nguyễn Nam Sơn; Getting off the horse, asking for directions, Playing Tam Cúc, The fortune teller by Thang Trần Phềnh; The letter by Tô Ngọc Vân are the first silk works introduced abroad. In addition to the national theme that raised the curiosity of viewers, these first silk paintings were all carefully researched by the artists, created using classical methods of representation and composition. Silk paintings are drawn in many ways about customs but are deeply researched in terms of artistic expression of shape and color.

TRẦN VĂN CẨN (1910-1994). ‘Two ladies before the screen’

45 × 48 cm. Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

TRẦN BÌNH LỘC (1914-1941). ‘A dancer in Campuchia’. 1936

Silk. 32 × 56 cm. Việt Nam Fine Art Museum

Combined with that are Vietnamese characters, mostly farmers in the rice fields, living and cultivating, exchanging goods. On the soft silk, Vietnamese working people are brought into the painting with a new, lively style, close to reality. The dark and light brown colors on the clothes, the black colors on the hair, the corners of the eyes, the pants, the dotted colors of the Tonkin jasmine, the hibiscus color on the belt, the strip of the yếm, the light green of the banana leaves, the bamboo, the yellow color floating on the duckweed pond… are very close to the real life of the countryside. The flesh, the silk pants leave the ivory white background of the silk more clear and airy, corresponding to the gentle space.

The way of mixing colors is also not exactly like watercolor: There is also the use of Chinese ink, vermilion, sometimes using mollusks’ shell to mix colors. Using Chinese pens and the way of playing with dark and light strokes, drawing strokes like dyeing colors into the silk is completely different from the European watercolor painting style. Putting the colors down is like soaking the colors into the silk fibers, each time trying to play with a color. Each artist knows how to skillfully place soft color on carefully studied image according to the model: a sophisticated combination between the reality of the image and the spirit of reality through national color harmonies. The color were bold, the white silk was clear and deep like the sky.

Silk paintings in the 1930s could be solid in composition, warm in color harmonies, discreet and flexible in brushwork: these were the characteristics of the national visual style originating from agricultural life that was still quite tightly maintained.

Nguyễn Phan Chánh introduced himself to the European public with the most attractive and valuable paintings: Bowl of rice, The busker, Washing dishes at the pond, Washing rice, Playing Ô ăn quan, The noodle vendor, etc. The law of value has further promoted the art of silk painting. Since 1932, there have been regular exhibitions of Vietnamese paintings in France in which silk painting occupies a key position, while lacquer is still in the experimental period. Tô Ngọc Vân, Mai Trung Thứ, Lê Phổ and Lê Thị Lựu all painted silk. From 1931 to 1937, silk paintings were representative of Vietnamese painting at world exhibitions in Paris, Brussels, San Francisco, Batavia, Hong Kong, Tokyo, etc. In France alone, Vietnamese artists exhibited at major annual exhibitions such as the Exhibition of French Artists and the National Exhibition. In these exhibitions, which had tens of thousands of works, Vietnamese painting first became familiar with the world public and first introduced a modern school of visual arts that was born in Hà Nội. Until recent years, Paris still printed paintings by Vietnamese artists from the period 1930-1931 (as in the collection Asian Painting – History and its wonderful beauties. Pictorial Publishing House, 1954).

MAI TRUNG THỨ (1906-1980). ‘Music’. 1946. Silk. 80,5 × 63,5 cm

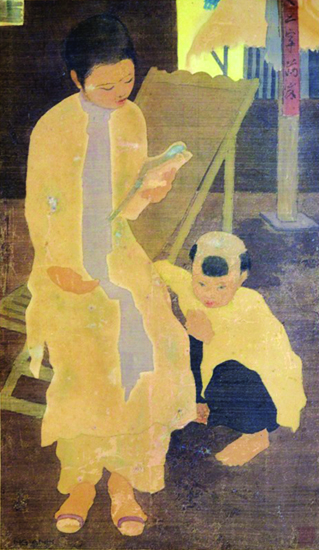

NGUYỄN TIẾN CHUNG (1914-1976). ‘Going to Tết market’. 1940

Silk. 90 × 56 cm. Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

After the period of 1928-1933, silk painting developed differently. Tô Ngọc Vân painted more silk: Farewell, Tết flower market, By the Rooster and Hen rocks. Nguyễn Phan Chánh went into smaller frameworks, painted faster: Going to the market, The little girl washing sweet potatoes, Herding buffalo, Fishing village, Bringing lions, Back after going for firewood… The art of silk painting of the artists at this time was different from before. Tô Ngọc Vân was fond of colors, always wanted to change the brushwork and direction of description. He gradually brought the bold, fresh harmonies of oil painting to silk. Next to the oil paintings filled with the golden light of Cambodian pagodas and towers, the blue of Hạ Long Bay, he displayed several bright red silk paintings of peach blossoms, mixed with the brown shirts of flower girls, the green bamboo colors in the scene of a wife seeing her husband off on a horse (1935 -1936). The characters, drawings, and backgrounds were still based on the reality of that time, but the artistic trend foretold the steps of innovation, gradually changing the national form. He innovated the way of looking at colors. From dull brown – which he considered depend-on-old-things, he introduced blue-yellow-red harmonies that were filled with sunlight. He mocked the fake-old, fake-national paintings: “Drawing colors and adding a little Chinese ink? After painting silk, spraying coffee, strong water with vối, or hanging it in the kitchen to make it look old!”. He wanted Vietnamese silk in a different color form, he loved the new discoveries of the Impressionists and the Fauvists. The external colors made him move away from the meaning of the subjects expressed through images, although the core of expressing images was still based on the balance of reality. He gradually moved away from expressing the subjects and came closer to expressing sensations.

From 1935 to 1936, silk paintings gradually lost their ethnographic character. Artists wanted to affirm the development of a more unique style, wanting to innovate the creative style to reveal different qualities. The colors changed accordingly.

TRẦN ĐÔNG LƯƠNG (1925-1993). ‘Embroidery team’. 1958. Silk

53 × 84 cm. Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

NGUYỄN VĂN TỴ (1917-1992). ‘Remember’. 1988. Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

The next generation painted a lot on silk: Trần Bình Lộc, Nguyễn Tường Lân, Nguyễn Đỗ Cung, Nguyễn Anh… Each artist had their own unique way of painting. Nguyễn Tường Lân was liberal in the warm red-brown, green color combinations, some blurred, some bold such as: Portrait of Ms Nguyên, Landscape, Bamboo and water in the village (1935-1936). Trần Bình Lộc added charm to his character: Liên picking chrysanthemums. Nguyễn Đỗ Cung was more thoughtful and sharp in searching for style, from Scholar writing on Tết holiday to Portrait of a little boy wearing a conical hat, to the silk compositions of the Huế period, the artist experienced expressive styles. Before exploring and developing lacquer, Nguyễn Gia Trí had silk paintings with sharp strokes like Two young women in a rural scene, bamboo tinged with golden afternoon light. A unique silk technique followed the realistic perspective of oil painting. The next generation mostly specialized in silk painting: Trần Văn Cẩn, Lương Xuân Nhị, Nguyễn Tiến Chung, Nguyễn Đức Nùng… The subjects shifted from rural to urban life. The strong women working in the fields and on the river changed to effeminate urban women. The way of painting was more liberal, more diverse in style and color scheme but boring in perspective. The scene of daily life on the paintings was narrowed like a garden, a corner of a house, a room, and only the perspective of a few model characters. However, they still depicted realistically in method. From the silk paintings specializing in blue and white colors by Nguyễn Anh (1934-1935) to the silk paintings of Nguyễn Tường Lân in the years before the Revolution, a line of silk painting developed to a dead end, far from the shape of the characters. Nguyễn Tường Lân once declared: “Each of my silk paintings must be a beautiful tapestry of color.” The art lost its shape, the sickly poetry of silk paintings influenced the next generation of young people.

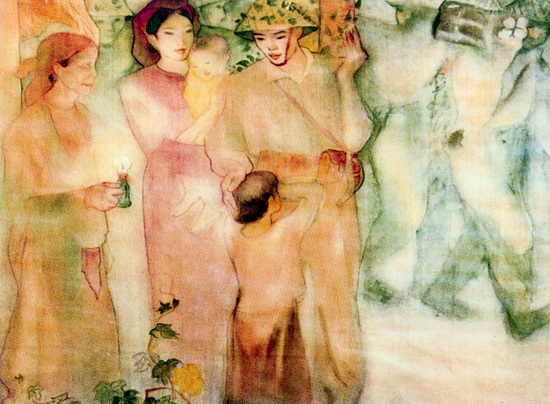

The practice of the August Revolution gradually brought about the right direction of creation for silk paintings as well as all types of Vietnamese paintings. Based on the Party’s outline for culture, national consciousness was correctly determined from content to form. Vague notions about national culture were gradually fixed. Traditional silk art had the opportunity to develop more healthily in the heart of the Revolution that was completely changing the country’s position. To commemorate the first anniversary of the August Revolution, August 1946, the National Fine Arts Exhibition presented a new aspect. Current events images: a child soaked in oil to burn a gas depot, a woman farmer plowing the fields depicted on silk paintings next to sketches of the famine of 1945, of the occupation in Bắc Bộ Phủ. Until the period of living in the countryside, along with the resistance against the French, silk paintings completely changed the environment and the subjects depicted. Each area organized its own painting workshop. Each field trip brought back sketches suitable for silk painting. The framework is smaller but the subject matter and composition have changed completely: guerrillas, marching, women on missions, mountain militiamen evacuating in caves, mothers helping wounded soldiers. In the South, Diệp Minh Châu painted guerrilla boats under the cajuput trees of Đồng Tháp Mười.

LÊ VINH (1923-2008). ‘Bế Văn Đàn’. 1958. Silk. 60 × 63 cm

Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

TRỌNG KIỆM (1934-1991). ‘Drop by the house’. 1958. Silk

63 × 47 cm. Việt Nam Fine Arts Museum

From 1948 onwards, after the National Arts Congress in Đào Dã, silk paintings were painted more, with a quality that far surpassed the early years of the resistance war. Before, silk were painted with flat surface, inclined to decorative shapes and colours, with gentle strokes. From then on, silk paintings used more light and dark, with richer, bolder colours. Many different models of people in different contexts: the Bắc Giang guerrilla, the soldiers fighting in the mountains and forests of Việt Bắc, the woman officer working in the plains of Zone 3, the militia in the coastal area of Cảnh Dương, the guerrilla areas of Cự Nẫm, Lệ Sơn. The beauty of silk has completely replaced the previous pineapple material. The gentle background of silk changes from ivory white to oak yellow, and muslin yellow. The ivory yellow of the silk with the joints of threads further softens the drawing, increasing the value of the material. The hand-woven silk of the countryside is even more suitable for the image of the difficult life during the resistance war in caves and in the mountains and forests from Việt Bắc to Bình Trị Thiên.

Silk paintings took on the major theme of people’s war, of the relation between the army and the people. In Khu Tư [Zone 4], Sỹ Ngọc painted The bowl on silk first; The Soldiers Pounding Rice, The Guerrilla of Cảnh Dương (Nguyễn Văn Tỵ), The Refugee Hub, The Green Seedlings (Phạm Văn Đôn); Zone 3 with The Officers Going to Work by Lương Xuân Nhị; Việt Bắc and The Refugees in the Cave by Trần Văn Cẩn. From 1951 onwards, there were many trips to paint of production and to participate in campaigns, and a number of new works were born: I Read Mother Listen (Trần Văn Cẩn); Celebrating of Land Reformation (Tạ Thúc Bình); Encounter (Mai Văn Hiến); Bế Văn Đàn Using His Body as a Gun Stand (Lê Vinh). The new generation of artists also painted a lot on silk: Phan Thông with Marching in the rain; Trịnh Phòng with The Guerrilla Behind the Enemy’s area in Zone Three; Trần Đông Lương with The teacher and students in the free zone, Trọng Kiệm with the scene of soldiers Drop by the house, etc.

Since the 1930s, silk paintings have developed from the genre of customs and daily life to the themes of revolutionary history and resistance. From the national form, art has gone deeper into realism, closer to the colorful fighting life. From national art with quality of the method of describing people in silk paintings has a social realism character, silk paintings have been formed and developed according to the requirements of the long-term resistance war against the French, although the generality of the works has not been as smooth as the previous type of custom paintings.

In the 1960s, the younger generation was educated in silk painting. They enthusiastically joined the resistance war against the US to paint the themes of industry or socialist agriculture, the long forest measured in years and months of the Trường Sơn road. Each time they going, a new phase of silk was born. It is necessary to mention Nguyễn Thụ’s silk paintings about the Northwest (1976), about the fire line of Zone Four; Thanh Ngọc’s silk about the mountains; Giáng Hương’s silk about the scenes of life in Trường Sơn (1972).

PHAN THÔNG (1921-1987). ‘Marching in the rain’. 1958. Silk

42 × 61 cm. Việt Nam Fine Art Museum

NGUYỄN THỤ (1930). ‘The evening’. 2009. Silk. 60 × 80 cm

Minh Đạo Collection, Hà Nội

In recent years, woman artists have appeared in silk art. The exhibition of paintings by woman artists in 1973 was a contribution to the development of silk painting. Phan Thị Hà with two paintings Pounding rice to feed soldiers and Fabric inspection; Minh Phương with Threshing rice in the harvest and Young people of mountain; Kim Bạch with Weaving wool carpets. Nguyễn Thị Phúc, Hà Cắm Dì, Hoàng Minh Hằng all have good works. Silk art itself has characteristics suitable for women. However, developing artistic attributes, bringing silk paintings into a combative orbit, transforming the ability of silk to new realistic attributes requires high and continuous creativity of thinking and sensitive emotions.

Some artists specialize in silk. From there, art and the artist’s ability develop uniquely. Nguyễn Thụ has experiments. Recently, he has painted valuable paintings: Planting rice in the mountains, A mother weaving, Mountain village (1976). His brushwork is lively, his color are deep, and have a strong shaping force. He’s just won an award at the International Exhibition in Sofia in 1979. Trần Lưu Hậu likes to find fresh ethnic colors like dyes that go well with silk fibers. Soldiers return to the village (1974) is a cheerful scene under the peach blossoms, and Beside Hmong village is a successful work of his in terms of composition and color. The old painter Nguyễn Phan Chánh (born in 1892) still maintains the role of “pioneer” of silk art. A series of lyrical works about the beauty of women, in the artist’s 80s, seem to have liberated a constrained view of the trivial details that “tell the story” of the subject. From Bright moon, eclipsed moon (1970) to Tiên Dung (1972), Kiều bathing (1973), Nguyễn Phan Chánh again moves to a dream world about the Beauty of the pure, innocent dawn. Such boldness in presenting characters freely can only be achieved at the age of 80, when seeing things as just a dream, a dream of Beauty without attachment, not bound by rituals and social formulas.

Recently, a foreign journalist wrote about Vietnamese silk paintings: “This art is simple and discreet, and seems too formal, too. Between the proud brilliance of lacquer and the heavy harmony of oil, silk paintings have an elegant, rustic nuance, a lullaby, a dream in the souls of simple farmers and children.”

Silk and lacquer paintings are two types of art that have contributed worthily to Vietnamese realistic visual arts. Those paintings have developed traditional folk culture with national specialties: lacquer resin and silk. They have absorbed Eastern techniques as well as European realistic rendering techniques. From traditional themes of portraits, customs, birds and flowers or decoration, they have transcended to describe the themes of labor and fighting, and have mentioned the character and activities of the classes of people in the revolutionary stages of national liberation and the construction of socialism. The strength of Vietnamese lacquer and silk paintings is the strength of youthful eyes, a bold way of looking at life on the path of social realism. Artists who create lacquer and silk paintings know how to escape from technical constraints, know how to find new things and absorb healthy initiatives of folk as well as the achievements of visual arts in the world.

Article of author Nguyễn Văn Tỵ posted on the website Tapchimythuat.com.vn