“Objects penetrate one another.

They never cease to be alive.”

— Paul Cézanne

Does a teacup feel? Does a sugar bowl have a soul? Does an apple love? Joachim Gasquet recounts Cézanne’s description of his fraught relationship with “those little fellows,” his still life objects:

“People think a sugar bowl has no physiognomy or soul. But that changes every day here. You have to take them, cajole them. . . . These glasses, these dishes, they talk among themselves. They whisper interminable secrets. . . . Fruits . . . love to have their portraits painted. They sit there and apologize for changing color.”

Cézanne’s interpreters have noticed that chatter—or, to the contrary, a resolute silence. Rainer Maria Rilke revels in the objects’ quiet absorption, the way they are “so wonderfully occupied with themselves.” Vasily Kandinsky tells us that Cézanne “made a living thing out of a teacup—or rather in a teacup he realized the existence of something alive.” For Roger Ballu, Cézanne’s natures mortes “are not dead enough.” More recently, Carol Armstrong has compared the “physical and formal associations between objects” to “the social and affective ties between people . . . the play of dominion and submission that mark human relations.”

As pleasurable as it may be to imagine the curmudgeonly Cézanne communing with pots and pitchers, apples and onions, what most animates his still lifes are the materials of their making. Self consciousness, Cézanne argues, is central to the labor of his art: “He becomes a painter through the very qualities of painting itself. By exploring its coarse materiality.”

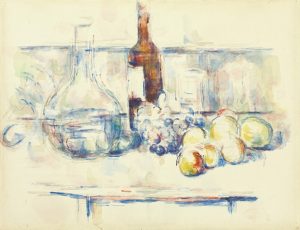

This material exploration, this self-conscious revelation of the possibilities and logic of common art supplies, results in a work that is “a repository of process,” to borrow Ewa Lajer-Burcharth’s words. The papery-ness of his sheets, the liquidity and translucency of his watery pigment, the silver-gray strokes of pencil—it is in them, to return to Kandinsky, that Cézanne “realized the existence of something alive,” achieved his self professed aspiration to “astonish Paris with an apple.” By creating equivalences between means and subjects, calling out paper by not painting it at all, and staging analogies among approaches and forms, Cézanne makes of his watercolor still lifes essays in the mechanics of seeing and creating.

Aqueous itself, watercolor perfectly represents liquid: washy blue and rose denote water in a half-filled carafe, conjuring its moisture, clarity, luminosity; deeper reds and blues together suggest purply wine in a tall bottle, lighter and brighter at the surface; deep indigo fills an inkpot. Unlike opaque oil paint or gouache, watercolor is also an apt equivalent for translucent glass, and Cézanne deployed curving strokes in pencil and paint, and patches of color, to establish dimensionality. Meanwhile, broken lines, often in blue, materialize the eyes’ own skips and starts, especially around glassware—vision’s part-by-part efforts of comprehension, made ever more challenging by reflections that move and change with shifting illumination. Watercolor’s transparent liquidity offers Cézanne an evocative way to describe shadow, letting it “bleed” across a surface, like the shade cast by a green jug on a table.

Paul Cézanne. ‘Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit (La Bouteille de cognac)’. 1906

For Cézanne, paper equals paper. Mostly unpainted areas of creamy sheets form the paper labels on wine and liquor bottles. Arcs of color or pencil indicate how these paper rectangles bow to adhere to a rounded form; as the “uppermost surface” in the composition, the label is, Armstrong points out, paradoxically “represented by the undermost surface.” Cézanne gives myriad other responsibilities to unpigmented paper in his still lifes, from representing the texture of those objects he so carefully composes on tables and sideboards (the bright white of a cloth; the shiny surface of porcelain; the glassy finish of enamel; the smooth burnish of bone) to emphasizing shape (an unpainted patch indicating the “culminating point” closest to the spectator; the hard edge of a tabletop delimiting space).

The work is not on paper, it is paper.

Usually relegated to a supporting, or background, role—indeed the very terms for paper are “support” and “ground”—paper is instead the central protagonist in Cézanne’s still lifes. The nomenclature “work on paper” is similarly misleading. The work is not on paper, it is paper. Watercolor’s luminosity—its very being—is wholly dependent on the sheet on which it is painted.

As an actor in Cézanne’s compositions, paper represents both opaque surfaces (from paper to cloth to porcelain) and translucent ones—those of glasses, carafes, and bottles. Contradictory terms like opacity and transparency, then, “stand in relation to each other,” as T. J. Clark has explained, “doubting and qualifying each other’s truth.” As we move from object to object, from one unpainted area to another, we must recalibrate our understanding of that creamy white. A similar contradictory analogy is made in the work, where the shape of the label echoes that of a nearby glass. The grapes, at center, meanwhile, are dense enough to block our view of the bottom of the wine bottle, yet are only scarcely defined by arcs of blue.

Thus we see that as much as Cézanne attends to the material logic of paper, watercolor, and pencil, he also, Émile Bernard writes with admiration, “transforms his means, bending them forcefully to his use.”

Source: MoMA