It was a large, zinc-roofed workshop that used to house the shovels and hoes of Lục lộ Department. In 1925, it was both the private residence of Mr. Director Tardieu and the meeting place for the newly admitted students. In the middle of that first nest of modern Vietnamese Fine Arts were great paintings by Tardieu, now in the lecture hall of the College, which at that time had not yet faded with moss and mold as it does today, and always shone with the red-yellow light of ripe orange. In front of the painting, a long ladder stood tall, reaching to the top of the painting, and creaked every time Mr. Tardieu heavily stepped up to paint. That ladder, every day from above, looked down at us gathered at its feet, as if both sympathetic and mischievous. All day long it looked at Lê Phổ’s very artistic and orderly messy hair, always solemn on a stiff collar with corners, around it was a long black tie. It slyly witnessed the unfortunate incident of Nguyễn Phan Chánh, which happened exactly twice a day, morning and afternoon. The thing is, he had a faded umbrella that he carried every day and he insisted on keeping it by his side while he sat drawing. Mr. Tardieu, seeing this the first day, was not afraid of displeasing him, so he put the umbrella on the ladder, but… the next day, and the day after that, and every day, the job of keeping the umbrella by his side was Phan Chánh’s, the job of putting the umbrella on the ladder was Mr. Director Tardieu’s. As for our ladder’s job, every time the umbrella was put on it, it would make a “clack!” sound, bang down as if mocking, and count one more time.

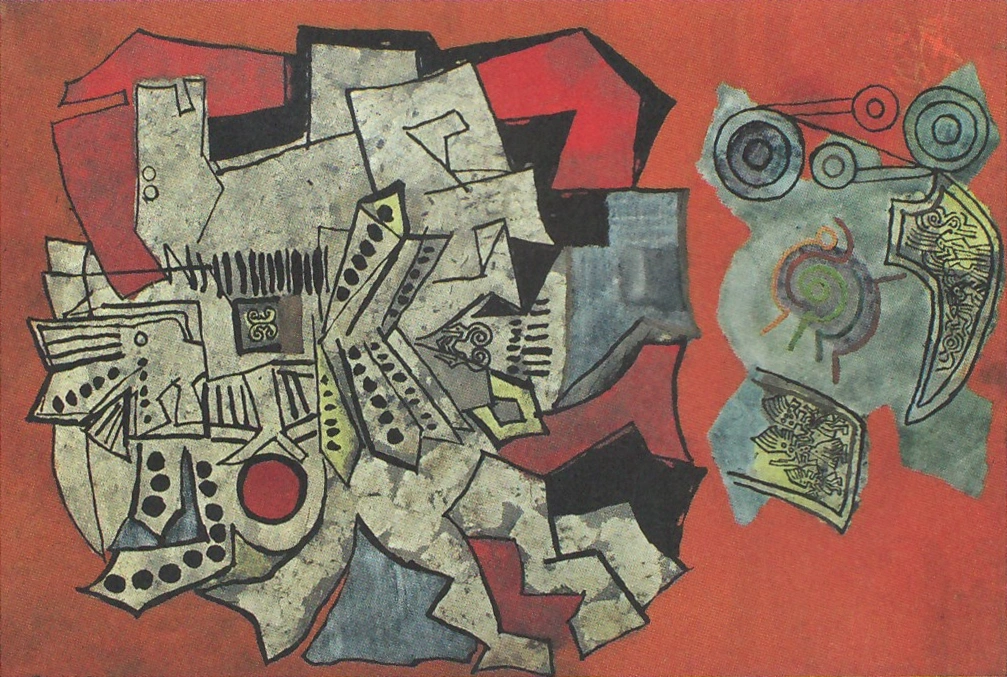

Victor Tardieu and the painting on wallpaper made for the Great Lecture Hall of the Indochina University

(Faculty of Medicine) while still at the site of the Indochina College of Fine Arts (completed in 1927)

Mr. Trần Phềnh (third from left) with a French theater group on the

steps of the Hà Nội Opera House. Around 1917-1918

Sitting in one corner was Mai Trung Thứ, his lips protruded, his eyes bulging as if they wanted to run up to the body of the nude model he patiently drew standing. Sitting in the corner was Lê Văn Đệ, also absorbed, also patient, and occasionally, delighted by something no one knew, he would laugh, like a firecracker suddenly going off…

If the Fine Arts College did not exist! All the enthusiasm for fine arts would have been wasted on an unjust art! The god of art was Mr. Trần Phềnh, the person whose talent we had previously admired and considered a very high and difficult goal to reach. His art was based on skill and familiarity; the talent was to create red and green colors to paint on the drawn shapes exactly according to the photos, without needing artist’s emotions.

The first entrance exam to the Fine Arts College, Mr. Phềnh attended. We looked at him longingly, thinking that his position was not to be a student at the Fine Arts College, but to teach. In the examination room for the nude drawing, people stared at the rhythm of his hand moving on the drawing page; taking out a pile of small and large pencils on his ears, and rolls of polishing paper of various sizes and shapes, skillfully like a barber removing earwax for a customer, he lightly scumble with the eyelashes or wrinkles on each painting he made to express the model. The exam results surprised everyone: Mr. Phềnh was failed and lost his sacredness, along with his art.

Happy, passionate, confident, we entered the gate of the Fine Arts College to the inner palace of “Beauty” and soon caught a glimpse of how alluring it was! Are there any boys and girls who are as infatuated with beauty as we are with “Beauty”?

Nguyễn Phan Chánh, 1924

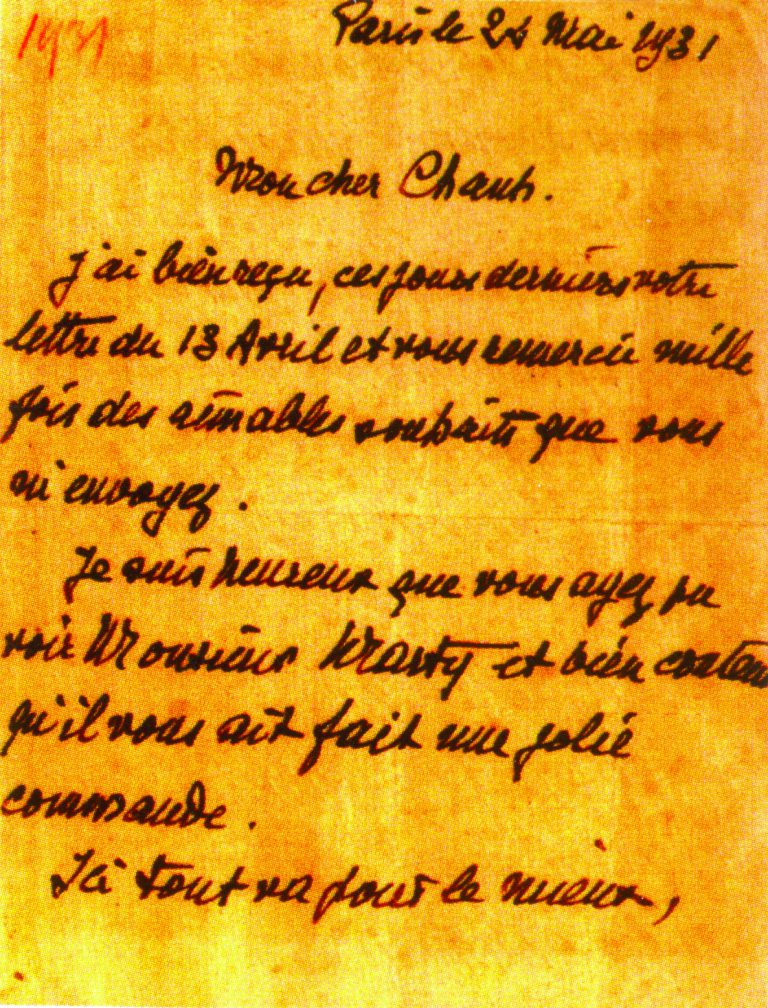

The first page of Victor Tardieu’s letter to Nguyễn Phan Chánh speaks of

the college’s success at the 1931 Paris Exhibition (Paris, May 24, 1931).

In the world of those passionate souls, when people talk about famous Chinese, Japanese or European-Western artists of this century and the previous century, they separate their personalities and talents, just like people who have known each other very well, who have understood each other too well, even though they have only read about them or seen color photographs of their works? But who has understood before falling in love! In the work, there is something sympathetic, an atmosphere in which our students of the Fine Arts College feel comfortable and at ease. Don’t ask them why. They will only be able to imitate Montaigne and answer: “Because it is Hokusai, Manet, Cézanne, Van Gogh… because it is us…”

The contact of the Fine Arts College with the public began with the first exhibition around 1928-1929, right at the Fine Arts College. There was a painting of a sad girl with her hair down by Lê Phổ, a painting of a girl sitting on a bed with watery eyes as if about to cry by Mai Trung Thứ. There was a gentle painting of an old man by Lê Thị Lựu, heavy, dark brown paintings of countryside by Nguyễn Phan Chánh. Silk paintings had not yet been created. They were just paintings with rough and gritty surface. Not as smooth and shiny as the photos as the public liked. Newspapers commented cautiously. People criticized the paints of Lê Phổ and Phan Chánh as “muddy soil”. Did they expect that it was a compliment? A daily newspaper sarcastically criticized Mai Trung Thứ’s paintings as “lewd”. It was only because the artist painted a woman wearing shiny silk pants and a blouse, without additional outer covering…

In art field, the general trend at that time was to mold the image of a young woman to look dreamy, innocent, and melancholy. It might be a trace of the times! Who could draw watery, tearful eyes as well as Mai Trung Thứ? All of Lê Phổ’s woman characters had dull eyes, without a lively glow.

NGUYỄN PHAN CHÁNH – Carrying firewood. Circa 1932-1938. Silk

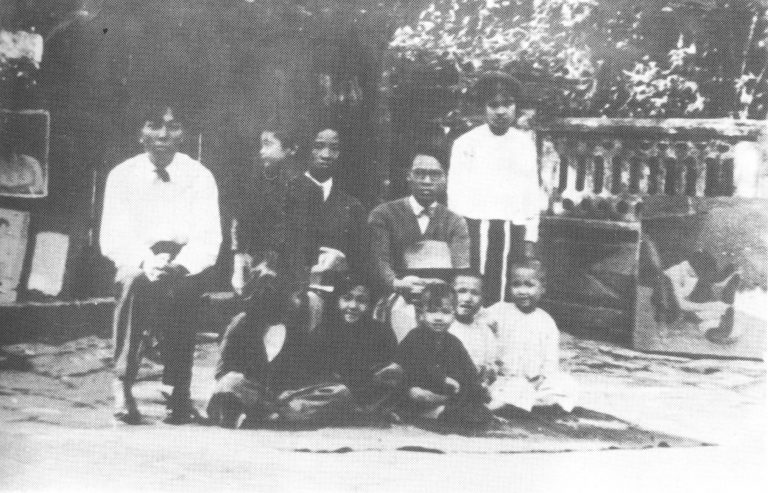

Students of Indochina Fine Arts College on a field trip in the countryside,

around 1928-1929, from the left: Mai Thứ, Tô Ngọc Vân, Lê Phổ

Artists wanted their works to look Chinese or Japanese; they stamped their paintings with tiny red marks, wrote long lines of Chinese characters, and depicted rocks and trees in styles only seen in Chinese paintings. “Truly Chinese!” was a compliment the artist readily accepted. This comical context revealed a pretentious attitude, prioritizing formality over genuine emotion, as if the artwork only had an outward appearance without a soul hidden within!

1931… The colonial exhibition in France introduced the French public to Vietnamese paintings for the first time! I am referring to the silk paintings, neither Western, Chinese, nor Japanese, by Phan Chánh, the person who stubbornly held onto his umbrella back then, the person who unexpectedly started the unique Annamese silk painting movement.

Tô Ngọc Vân

(This article by Tô Ngọc Vân was published in Xuân Thu Nhã Tập journal in 1942,

the spelling of the original text has been preserved)

Source: Tạp chí Mỹ thuật [Fine Arts Magazine]