Inspired by Winter’s arctic mountains and skies, Norse painters attempt to capture the magic in the cruelty of nature

When the solemn descent of December’s darkness wraps a solstice blanket of eternal night over Norway, a necessary mood of patience and melancholy colors the hushed country. Light leaves this arctic land for months, and a cruel winter covers the earth in frozen snow, now barely touched by the exiled sun. South of the perma-frost, black and bare-branched trees split the sky and bone-cutting breezes blow down from the smooth slabbed mountains of the North, whistling their winds over glacier-carved islands and fjords and lakes, whipping through the sticks and driving clinging crystals loose in icy showers sparkling and brilliant in the frozen air. The space between our earth and other dimensions of magic and myth is compressed here and the tight tension of waiting for light to return twists against the resistance of the merciless landscape, relentless in its aloof austerity. Neither kind nor unkind, this Norse land will kill the ill-prepared with careless indifference, and humanity is awed, dwarfed and damned by the weight of heaving nature.

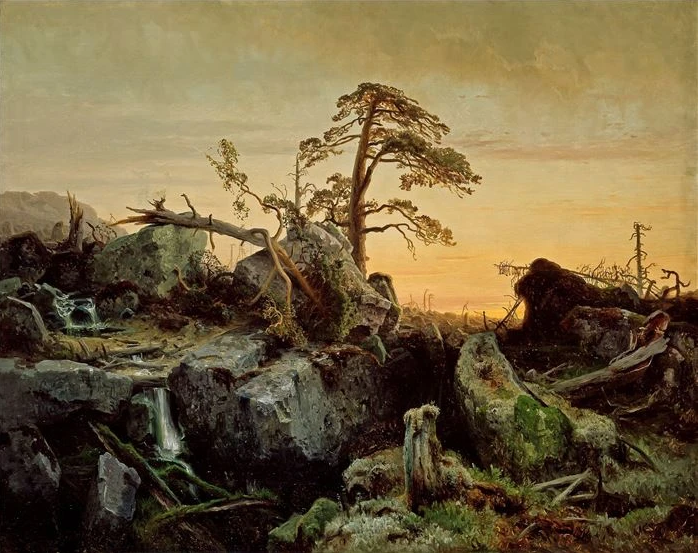

August Cappelen, Dying Primeval Forest, 1852, Oil on Canvas, 93 cm × 136 cm,

Collection of Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, Arkitektur og Design, Oslo

As the romantic mood sweeps the Western world, cast an eye to sublime painters of the North. Norwegian painters watching the solemn skies and the unchanging mountains held the land in righteous awe as witnesses to the disdain of its elements for the attempts of clinging life to survive. The Northern winter teaches that geological Earth isn’t cruel, it is relentlessly indifferent, inevitable and truly sublime. August Cappelen painted above the edge of the water, where tough trees split and cracked, splintered beneath the weight and glacial pressure of the heavy sky. His Dying Primordial Forest saw life in its desperate battle for survival, gripping by root to the edges of ruthless and relentless rock. This was no country for the naïve. Joachim Frich’s Landscape from Telemark shows the same battle of mighty trees stunted by the struggle, collapsing on the edge of the forest clearing, where water pools collected and a lonely reindeer passed through a glade of rotting trunks overcome by the elements.

Joachim Frich, Landscape from Telemark, Oil on Canvas, 1852, 93cm × 136cm,

Collection of Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, Arkitektur og Design, Oslo

To witness the sublime is to be at the point of crossing a threshold, at the boundary that separates worlds, beholding something between the sphere of man and the realms of the divine. To Edmund Burke the sublime was characterized by astonishment, fear, pain, roughness, and obscurity, while the beautiful was revealed in calmness, safety, wellbeing, smoothness, and clarity. Both could be experienced with pleasure – but astonishment was the highest degree of the effect of the sublime, which had the power to induce a state of frozen and focused wonder, closely associated with horror. Immense scale was fundamental – the vast size of the ocean was so great as to inspire fear, and great depth grander than height, and the infinite was the source of awe.

Peder Balke, View of Torghatten and the Church of Brön Öe, Oil on Cardboard, 27.8cm × 37.2cm

Surely the pragmatic Peder Balke knew no church could compete with the eternal span of nature when he painted holed and holy Torghatten, the great granite slab backlit by low sun hung beneath the blackened sky of winter – an unblinking fiery eye between air and ocean staring at the hopeful little church at Brön Öe, a symbol of little man’s austere religion in absurd confrontation with the power of the elemental and everlasting sublime, a ridiculous conceit here where the eternal stone shouts of the eons of ice which ground this glaciated landscape for thirty thousand years before Paleolithic mankind managed to follow his fortune toward the melting North. Tectonic time created this, in grinding and grating movements of planetary scale.

Inspired by awe, man must make metaphors and allegories to soften the sublime: giving personalities to the unconcerned precipices and deep fjords; telling sacred stories to simplify the unimaginable; reducing the scale of the lethal landscape until the windswept mysteries of the hardened land, the rising steam of the freezing sea, and cruel, unforgiving gods seem intertwined – and such tales made space for heroes to tread their prints into the savage snow travelling the mythic land of awe and wonders. In truth, humans were newcomer dilettantes skimming the surface of this stone, ice and oceans. The image makers knew the mountains were the true guardians of the land.

Harald Sohlberg, Winter Night in the Mountains, Oil on Canvas, 1914, 160.4 × 180 cm,

Collection of Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, Arkitektur og Design, Oslo

High in the living mountains, Harald Sohlberg found the blue depths and the deep star of his Winter Night in the Mountains, and silhouettes of black and leaf-blown trees borrowed from Da Vinci’s divine altarpieces wore the filigreed and crackling coat of darkness, forming black nets cast around the mutating trunks, cutting the sensual shapes of the sleeping peaks, ogreish and alive.

Peder Balke, Stetind in Fog, Oil on Canvas, 58.5 × 71.5cm, 1864, Collection of

Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst, Arkitektur og Design, Oslo

Balke’s knifed Stetind in Fog cuts the iconic slab of his mountain from the paint with a savage and slicing confidence matching the tension between man and the deep millennia that passed before him. Stetind, the wedge, the anvil, testament and strata of the ages, a monolithic memorial to time.

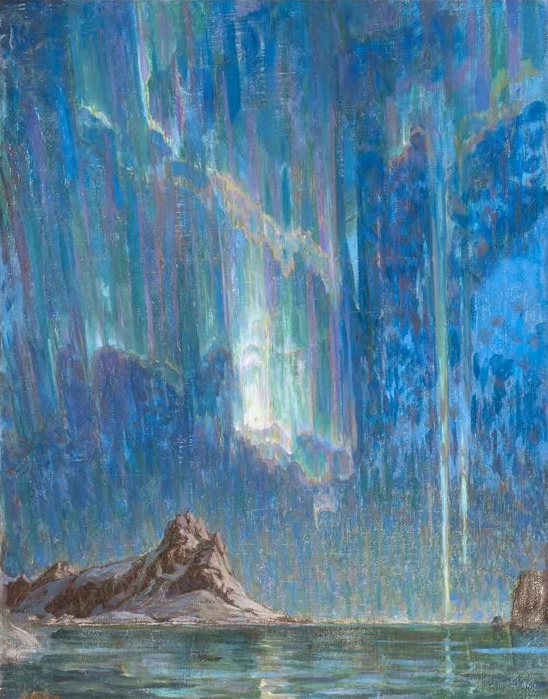

Anna Boberg, Northern Lights. Study from North Norway, Oil on Canvas, 97cm × 75 cm

Though the savage spill and span of time inseminates the darkest Northern landscapes, there is a gentler, sunlit side to Norway’s scenery, an organic and vibrating life, though it stays subsumed beneath sublime visions. On clear nights the long starred and twilit sky is stained by the ethereal glow of green and colored lights as the shadowed sun’s magnetic storms cascade over our planet, bathing the silent world in their soft magic, enchanting their audience with hypnotic power. The Northern Lights are the quintessence of the elements, the embodiment of the aetheric, a mystic sign for seekers. The Sami people who first came to Northern Norway as the ice age withdrew don’t like to look too long at the lights, fearing their influence. To the Vikings, they were reflections from the shields of Valkyries, and showed fallen warriors the glorious path to Valhalla. Anna Boberg tried to find their majesty in her Northern Lights – Study from North Norway, painting their drama in a blue and purple firmament hanging over the Lofoten islands, and Balke sketched them in his Northern Lights over Coastal Landscape, hoping to express the solemn spectacle over the curving coastal islands scattered close to the North Sea shore, as erratic bluestone and granite boulders rose from the freezing water and streaks of light poured from the sky. Both seemed to know the glory and serpentine shimmering and the slippery movements of these lights could never be caught in the stillness of paint.

Peder Balke, Northern Lights over Coastal Landscape, Oil on Paper, 1870, 10.5 cm × 12 cm

In man’s search for meaning, the landscape is a book, and the elements are there for reading sooth from shift and season. Lars Hertervig’s The Tarn followed Cappelen’s path into the wet wasteland, where steam rose from the Paleolithic pools of Spring’s melt and formed strange pareidolic clouds begging for interpretation and drifting into dreams, and he pursued the beauty and mystery of the clouded country in his Island Borgøya, where the granite mass of grey stone floats upon a mirrored ocean suspended above a Springtime shore of light, but even there, though the clouds formed subtler shapes, and Hertervig found lighter forms when the ice gave way to the arrival of the Summer lands of everlasting days and nightless nights, sublime nature was still the power. There were no gods there but the land itself.

Lars Hertervig, The Tarn, 1865, source: Nasjonalmuseet

Lars Hertervig, Island Borgøya, 1867, source: Nasjonalmuseet

Written by Michael Pearce

Source: Mutual Art