30 years ago, on December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union announced its end after more than 70 years of existence with glory and bitterness, leaving a blank and chaos in politics, culture and art continue until today. 30 years – a time close enough to remember relatively, but also far enough to be able to draw necessary lessons for today and tomorrow.

For Soviet Union art, no matter what form of discourse, no one can deny its uniqueness in the history of art with its influence on a global scale in twentieth century. An objective view of Soviet art is a difficult task for any researcher, whether in Russia, the West or Việt Nam, because the socio-political legacy of this union still has an impact to the current world, making people more or less unable to help but fall into prejudice. Basically, when mentioning Soviet art, people often immediately remember “socialist realism” (Социалистический реализм), a movement that spread throughout socialist countries in the second half of the twentieth century. But in addition to this mainstream movement, Soviet art also has other important contributions that previously, for a number of reasons, were not properly recognized.

Socialist realism – The mainstream

The term “socialist realism” was first mentioned on May 23, 1932 by Ivan Gronsky in the Literature newspaper, then was used by the Soviet government as an official policy for writing and criticizing literature and art, in all fields from literature, architecture, painting, to music, cinema…

Socialist realism is an inevitable choice, consistent with the philosophical, political and social views of communism, as Marsim Gorky said: “Socialist realism affirms existence as is action, as creativity, with the goal of arousing and continuously developing core human abilities for the victory over the forces of nature, for protecting health and prolonging life, for great happiness blessings throughout the earth, in which every human being is a part of the unity of the great human family.”

That humanistic and respectful perspective for working people actually did not appear only in the socialist era. Back to the time before the revolution broke out, from the late nineteenth century, the art of the Russian empire produced a golden generation of realist masters of writers, poets and painters. In fine arts, we can mention the Mobile movement (Передвижники), which focused on the theme of life and landscape associated with the Russian people, typically artists such as Repin, Surikov, Shishkin, Perov, Kramskoy… These artists organized regular traveling exhibitions, promoting art to working people instead of just the aristocracy and bourgeoisie before. The Mobile movement had a profound influence on the art world as well as ingrained itself into the cultural awareness of the Russian people. In fact, it lasted until 1923 before ending. Therefore, for an union with the ideal of serving the working people, the choice of realism is very understandable. Even today, many people still consider Russia a citadel of realism and humanism, in contrast to the storms of contemporary art, but perhaps that origin is not really from the Soviet period but from the time of the Russian empire.

The basic principles of socialist realism are:

First, works of art must conform to the aesthetics of the masses, using folk and popular materials. Lenin said: “Art belongs to the people. The deepest roots of art must be felt and found in the lives of working people. An outstanding example of the principle of “art serving the people” was in 1932 when the famous contemporary French architect Le Corbusier presented the project of the Palace of Soviets in Moscow with a modern style, Stalin responded: “I’m not an architect, I don’t know much about architecture, but I know for sure that the Soviet people do not appreciate it.” And Stalin’s point of view is not unreasonable when we look back at modern architecture, urban areas and painting throughout Western capitalist countries as “similar” to each other, it is difficult to distinguish nationality, while art of the Soviet Union, especially during the period of Stalin’s rule, has its own characteristics that are difficult to confuse.

Second, art must show the peaceful lives of people, so that they fight for a better, happier life for everyone. Soviet art themes were often people’s real lives, fighting for and building the fatherland. In particular, propaganda paintings are a genre that has been pushed to a high level, a “speciality” only found in socialist countries. Today, we can think that this second principle is rigid and one-sided, it does not allow artists to fully exploit the dark sides of society or the hidden corners of the soul, but we must also admit that it also has the advantage of requiring art to be humane, evoking good things for people and society. If we compare socialist realist works with many contemporary works around the world like fetal formaldehyde, feces, rocks, or lifeless penises… then we can be immediately scared and sick of those non-way and crude “contemporary” people.

Third, art must express the process of development in a dialectical materialist way, every detail in the work can be explained. We can see this clearly in the way character shaping are always built with social context in novels and movies, or in the very strict composition in architecture and painting. Especially in the field of art criticism, until today, this third principle is still very current. We cannot adequately criticize any artist or work of art without placing it in a socio-historical context. Although art is not always rational and comprehensible, if there are no “prejudices” or “moral principles” to self-reflect the “floating” nothingness then the risk of turning art into easy fun, even rubbish, is real and is happening to a part of contemporary art today.

In addition, monumentality is also a characteristic of Soviet socialist reality with great monuments such as “The Motherland calling” in Volgograd, epic novels such as “Peaceful Don river”, massive constructions such as Moscow Comprehensive University Building. The belief in the power of the masses, of proletarian internationalism, and the open, universal character of the Soviet people may have encouraged a large-scale view of beauty.

After about 60 years of wearing laurels, socialist reality ended its historic mission when the Soviet Union collapsed. From now on, although no longer in an official position, the spirit of socialist realism is still very strong in the post-Soviet space, having a certain influence on the contemporary world. The nuance of reality has also changed, not as clear and rigid as in the Soviet era, but with the addition of fiction, poetry, and comedy, which we still recognize in the works of Zurab Tsereteli, Mikhail Shemyakin, Victoria Tokareva, Svetlana Alexievich…

The monument “The Motherland calling” in Volgograd, 1967. Artist: Y. Vuchetich, N. Nikitin

Avant-gard art before 1932

In addition to the “commanding height” of socialist realism, Soviet art also made its mark with other movements, including Avant-garde (Aвангард) and Constructivism (Конструктивизм), which took place vibrantly in the 1920s.

After the success of the October Revolution, some artists who followed the avant-garde movement before the revolution found it impossible to reconcile with the new social orientation, so they had to migrate to Western Europe and the United States such as Kandinsky (1920), Lissitzky (1921), Chagall (1922), Rosenbaum (1926)… and then they made important contributions to modern, contemporary Western art in particular and humanity in general. But there were also people who decide to stay like Malevich, Bulgakov, Pasternak… and they sometimes created quietly, sometimes strongly stood up to defend their artistic viewpoint, a viewpoint that leaned toward idealism and metaphysics, contrary to socialist reality.

In the early days after the revolution broke out, under the political patronage of Lenin and Trotsky, artists, architects, and poets marched forward with the working people, enthusiastically building a new art, breaking with the scholasticism of the imperial period. Artists together established new movements such as Avant-garde, Constructivism, Futurism… with a progressive perspective, expressing a changing era, looking towards the future. During the 1920s, Constructivist artists completely changed the concept of architecture, graphic design, movie. They encouraged the application of new scientific and technological advances in art, used abstract compositions, associated art with the times, and served new needs of society through the use of steel, concrete or designing multi-functional collective houses… That is also consistent with Lenin’s views on transforming Russia’s economy from an agricultural country to an industrial one. We can imagine that in the eyes of Russian artists at that time, the construction of the Soviet government was a large-scale artistic project.

The political power of art was promoted. Perhaps, because they were amazed by the progressive works of Soviet artists, artistic circles in Western countries before 1930 basically enthusiastically supported the young socialist state. Architect Le Corbusier thought of a super transportation-urban-architecture project connecting Paris with Moscow. Even the Soviet Union’s rival, Nazi Germany, had to take its hat off to this fresh art. German propaganda boss Joseph Goebbels, when watching “Battleship Potemkin,” told German filmmakers: “Make me a Potemkin!”

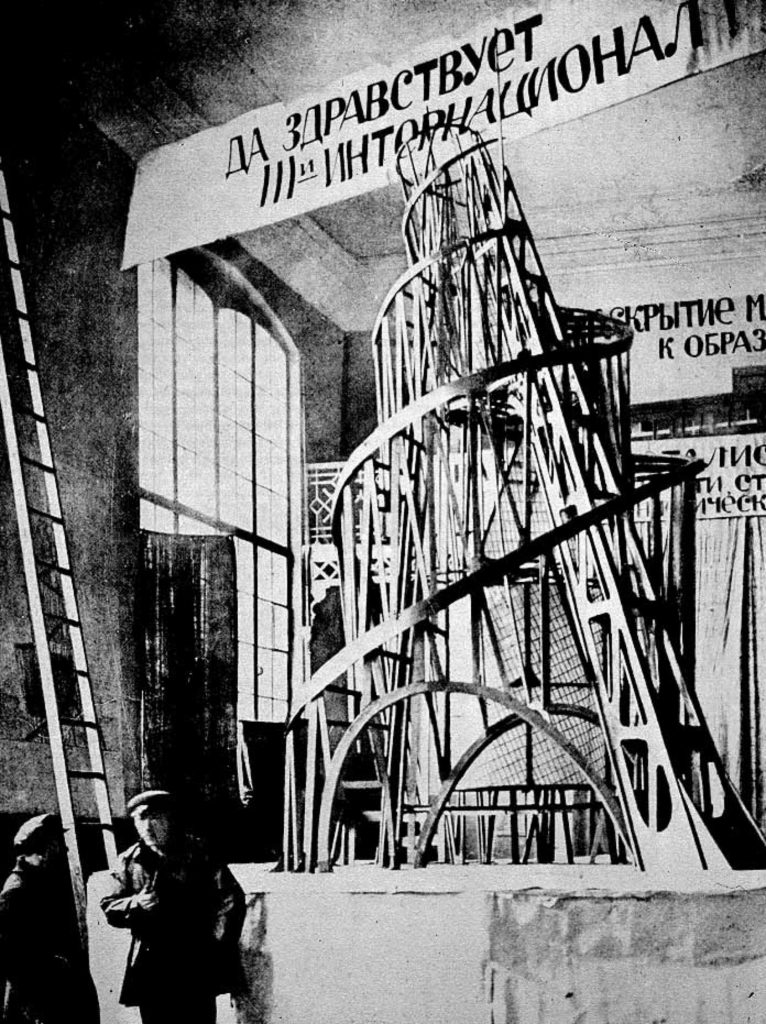

Model of “Third International Monument”, 1919. Artist: V. Tatlin

Underground waves of the mid-twentieth century

But after Stalin came to power, the direction of Soviet art and architecture turned 180 degrees. Stalin did not like abstract compositions, he required architecture to rediscover historical lines, and fine art to draw reality so that working people could “easily understand”. Malevich, the father of Minimalist and Suprematist art, was forced (or took it upon himself) to change his style to suit socio-political circumstances. Although Malevich’s paintings of this period could not ignore the familiar geometric colors, he had to “add” the human body to still see a bit of “realism”. Interestingly, this forced change in style gave birth to a new movement that critics today call Post-Supermatism.

In architecture, Stalin had famous buildings built in Moscow in an eclectic, retro style, which later became constructions which contributed importantly to Moscow’s identity such as Moscow State University, Foreign Ministry headquarters, Ukraine Hotel… Later, the architecture during Stalin’s power was called the “Stalin Empire” style by critics.

Regarding literature, the Stalin period witnessed many famous poets and writers having to undergo re-education, and during the Khruschev and Brezhnev era, they were classified as “parasites of society”. Some writers and artists with abstract, metaphysical, and futuristic tendencies still quietly created according to their personal viewpoints even though they were not published or exhibited. Sometimes, underground writers and artists stood up to defend their artistic viewpoints very fiercely. A typical case is the writer Bulgakov, author of “The artisan and Margarita”, one of the best novels of the 20th century. When the debate about literary ideology was fierce, Bulgakov did not hesitate to publish novels and plays that were full of fantasy and spirituality. Although the writer’s works were cut and discontinued, it is interesting that Stalin liked them very much. That’s why when Bulgakov applied to emigrate abroad, Stalin personally called the writer, advising him to stay.

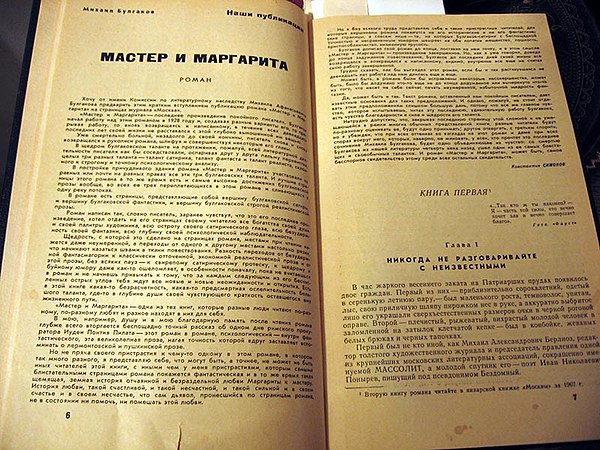

First printing of M. Bulgakov’s novel “The artisan and Margarita” in 1966

Unorthodox Soviet art in the period 1960-1990

Around the late 1950s, unorthodox trends opposed to socialist reality were gathered into a movement called Soviet Unorthodox Art (Неофициальное искусство CCCP), which was hoped to be approval from the new leaders after Stalin passed away. After taking power, Khruschev abolished the Stalinist architectural style and asked architects to change it in a direction closer to the architecture of Western countries, creating a premise for the Soviet Modern architectural style to shine and last until the 1990s. Basically, Soviet architecture during this period approached Western architecture, with a number of bold works appearing in remote republics such as Ukraine, Georgia…

But the opportunity to change art did not appear. On December 1, 1962, at the Manezh Exhibition House in Moscow, an exhibition celebrating the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the Soviet Fine Arts Association took place titled “New Practice”. There are displays of works by Pioneer artists with paintings in Symbolism, Formalism and Abstraction. Khruschev, by invitation, was also present at the exhibition. He got mad and did not hesitate to swear right at the exhibition. The general secretary commented on the paintings right at the exhibition: “What the hell is this face? Don’t you know how to draw? My nephew can draw even better. Do you have a conscience or not?” Two weeks after the meeting, Khruschev said: “Artists studied with the people’s money and ate the people’s bread, so they had to work for the people. Who do artists work for if people don’t understand what they’re painting?”

But the artists continued on their way. Now, in addition to continuing the glorious tradition from the early revolutionary period, there is also interaction with contemporary art in Western Europe and America. They quietly organized exhibitions in apartments instead of in exhibition halls or museums. Groups in cities were born one after another such as the Odessa Nonconformism group, the Moscow Concept group, the Siberian Undergroud group, the Lianozov group… Typical representatives include Mikhnov- Boitenko, Sokolov, Kabakov, Khrusch… Around the years in the late 1980s, unorthodox art gradually gained recognition, most notably with Sotheby’s auction of Soviet contemporary art in Moscow in 1988.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the artists and artworks of the Unorthodox Art movement began to be honored in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union, with highlights being famous exhibitions at the most famous museums in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. In particular, on December 1, 2012, on the 50th anniversary of the Manezh event, the Russian state organized the exhibition “Manezh is like that”, gathering together the works displayed on December 1, 1962 with gratitude to brave artists who seem to have been forgotten.

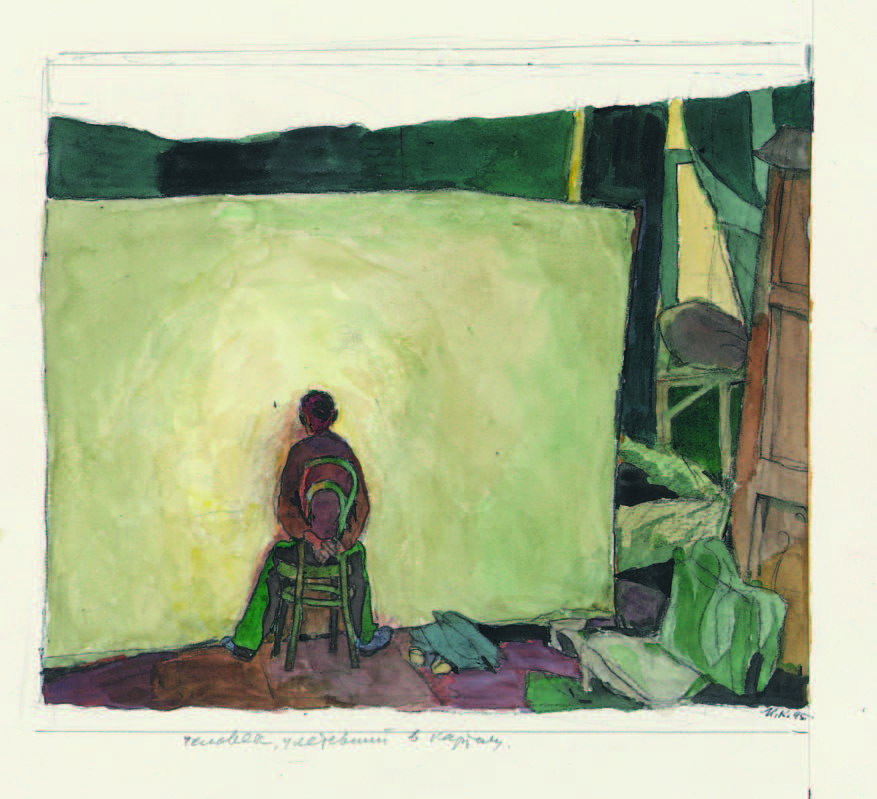

A person flying in his painting, 1988. Artits: Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

A few comments

From the epic song of Soviet art, an art that is unique in world history because of its socio-political conditions, its aesthetic principles have been and probably will be unlike any other era or any other cultural space, some observations can be drawn as follows:

First, in any art scene, there need to be different movements to complement each other, even though the government may support a certain dominant movement according to the model of “commanding height”. The movement of Constructivism before 1932 and Socialist Realism after 1932 were the “commanding heights” in Soviet art.

Second, realism never dies, even if it is overshadowed at a certain period, because it is always a necessary counterweight to the rapidly changing new “contemporary trends”. Conservatism is sometimes necessary so that art does not become easy and trivial.

Third, politics cannot impose its will on art absolutely. Even an iron-fisted government like the Soviet Union could not do that. Even Stalin had to find a way to relax unorthodox artistic movements to a certain extent, which is typical is the way he treated Bulgakov. Sometimes, the unorthodox region will bring glory to that art at some later point.

Fourth, artistic ideas are not only created by artistic people (artists and critics). In the Soviet Union, the role of politicians was important in creating socialist realism. In current Russia and Western capitalist countries, tycoon collectors are influencing the direction of art, through the market.

Fifth, works of art must be created from the artist’s inner needs, as an important principle that Kandinsky once wrote about. If an artist creates works that tend to be patriotic and love for the regime, then it must be true love from the bottom of the heart. Or if an artist’s aesthetic ideology is different from the orrthodox ideology, it must come from deep within the person and not be influenced by some external factor. Fortunately, many works of Soviet art movements were created from the inner needs of the artists, and with every perspective, peaks appear.

Recently, there are opinions that in countries where art is censored, it is difficult to have top-notch works. But the reality that happened in the Soviet Union shows that that statement is not entirely correct, even though a “breath easily” artistic environment is still better. Masterpieces are created not only by the political environment, but more importantly by the national culture and the tireless will of the artist. Soviet art proved that in the strictest censorship situations there are still exception masterpieces, and in the most ostentatious propaganda environment there are still orthodox peaks.

Written by Vũ Hiệp