In 2016, Eli and Edythe Broad talked to Michael Watts about great art, great causes and changing the rules, including founding a museum to house their astonishing collection and help to regenerate downtown Los Angeles

In November 2015, the billionaire owner of two Shanghai museums paid $170 million at Christie’s in New York for Reclining Nude by Modigliani. Naturally, Liu Yiqian made headlines worldwide, but less for the Modigliani’s price than because he had bought it on his American Express Centurion card, and thus qualified for an estimated two billion Frequent Flyer points. As the newspapers pointed out, Liu had been driving taxis not so long ago.

When Eli Broad heard this story, the American entrepreneur smiled to himself. The circumstances reminded him of how he, too, had shocked the art world 20 years earlier; and he recalled the menial jobs of his own youth, from selling ladies’ shoes to operating a drill press, before he eventually amassed a fortune from insurance and building houses.

With wealth valued at $7.4 billion [in 2016], Broad has come a long way from his birthplace in the Bronx to become a superstar among collectors of modern art, someone whose patronage and philanthropy have earned him gratitude as ‘the Lorenzo de’ Medici of Los Angeles’. He is a man of great causes, a tycoon who’s not a philistine, a funder of museums, schools and scientific and medical establishments across America. Much of the secret of his success, he would say, has been in confronting entrenched wisdom.

It was Broad who helped legitimise in America the practice of buying great art on credit cards, as Liu Yiqian did. This was uncommon in 1994, when Broad raised his paddle and bought a 1965 Roy Lichtenstein painting for the relatively modest price of $2.5 million.

Back then, paying large sums for art by Amex was considered revolutionary, both by the art world and by American Express; even with Visa or MasterCard, the credit-card holder would have to be very affluent and personally known to the company. His purchase led to ‘a lotta cocktail chatter in New York’, as Broad now recalls in his dry, Midwestern way. This is an understatement; it caused utter consternation — and also changed the rules.

‘I win big and I lose big,’ Broad once said. ‘There is no middle ground.’ He has humorously compared himself to a hound dog truffling tenaciously for great prizes. Notoriously cost-conscious, he bought the early conceptual photographs of Cindy Sherman at $150 a pop (a print of her Untitled #96 went for $3.89 million at Christie’s in 2011), and enjoys a reputation when negotiating for being ‘unreasonably persistent’ (his own phrase).

Broad still has that Lichtenstein. I… I’m Sorry!, the artist’s signature comic-book image of a blonde shedding a big, fat teardrop, is now a trophy on display in Broad’s lasting monument to his career as a collector.

The Broad is a three-storey museum he has had built, at a cost of $140 million, to house the post-war and contemporary art he and his wife Edythe have been collecting for more than 40 years. The Broad name now joins a select group of eponymous LA museums, alongside Armand Hammer, J Paul Getty and Norton Simon, in what is arguably a new gilded age of private American art collections.

The Broad Museum, Los Angeles

The museum opened on Grand Avenue in September 2015 with a 49-piece orchestra in tuxedoes and a keynote speech by Broad’s friend Bill Clinton. Broad has known Clinton since he was governor of Arkansas, and Hillary Clinton was once his lawyer. The former US president told guests: ‘I looked up one day and Eli was in my living room, and my life has never been the same.’

Eli Broad is the son of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants who owned five-and-dime stores in Detroit after moving there from New York. The family name was originally Brod, to which his Americanising father added an ‘A’, but the young Eli wanted more than acceptance into American society; he wanted to stand out. He made his parents agree that ‘Broad’ be pronounced more distinctively, to rhyme with ‘road’, which has been the case ever since.

At 13, he was buying stamps clipped off envelopes and selling them to philatelists around the USA; at 16, he had made enough to pay $600 for a 1941 Chevy. He studied accountancy at Michigan State University and in 1956, aged 23, he launched his first major business, with $12,500 borrowed from his father-in-law and with a business partner related to his wife.

Donald Kaufman was a house builder, and their new company, KB Home, successfully tracked the post-war growth of American home ownership. Broad is still the only person to have created two Fortune 500 companies in different industries, firstly with KB and housing, then with SunAmerica, which sold retirement insurance to ageing baby boomers. In 1999, when the insurer merged with multinational AIG for $18 billion, Broad personally made $3 billion.

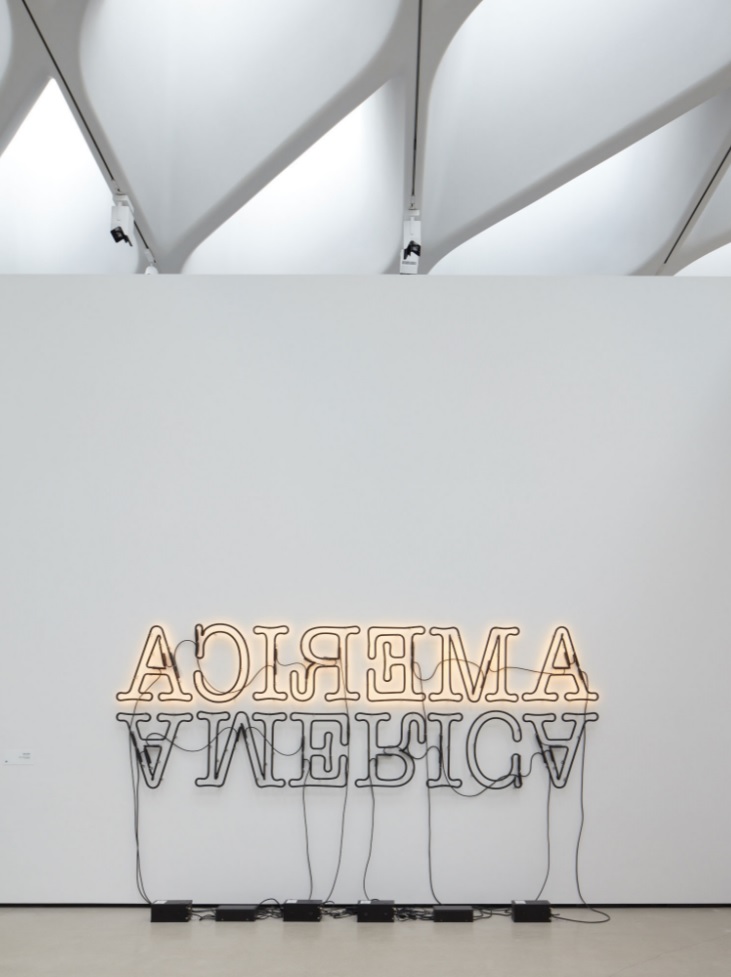

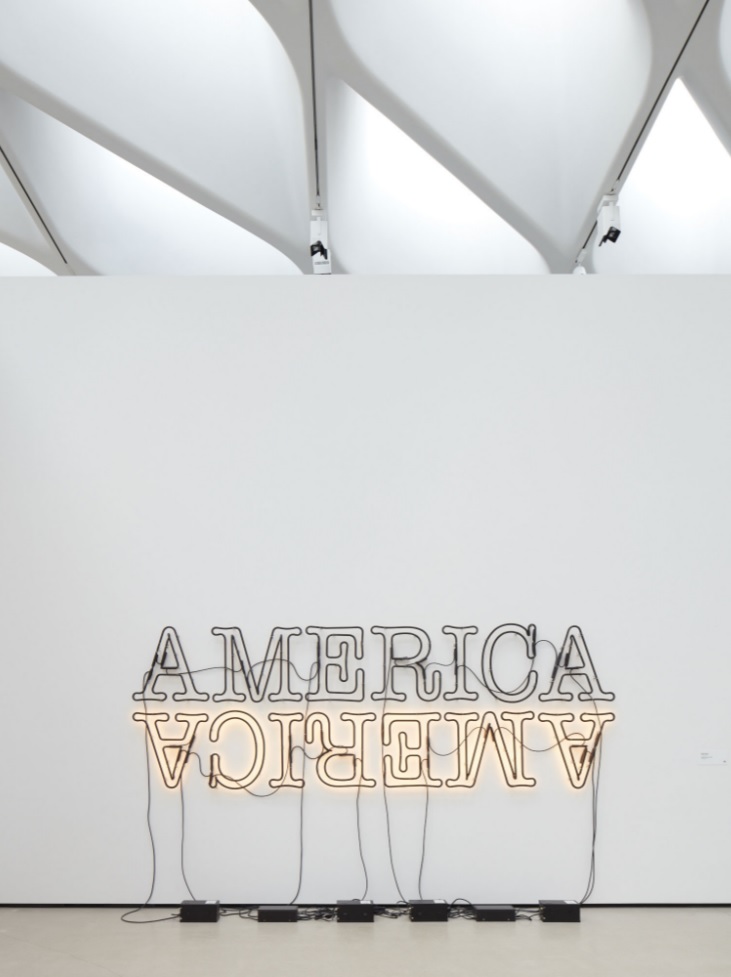

Glenn Ligon ‘Double America 2’ 2014 © Glenn Ligon

He retired that year to dedicate himself full-time to collecting art and what Edythe calls ‘venture philanthropy’. This doesn’t mean charity, they insist — that’s just writing cheques. They expect a return on their investment, in results if not in profits.

The Broads have now dispensed gifts of more than $2 billion — less on the arts, actually, than on science, medicine and education; $600 million alone has gone to the Broad Institute, a world-leading biomedical and genomic facility in Massachusetts, which they established with Harvard and MIT.

Through their education foundation, Eli has spent another $500 million on addressing his particular bugbear: the dismal state, as he sees it, of the US school system. But art is what truly obsesses him. ‘Life is richer when you live it among the dreamers’ is a favourite aphorism. He knows that posterity remembers artists, not accountants.

He and Edye, as everyone calls her, have been married for more than 60 years; she is three years younger than him. He had barely thought of art until they moved to LA and she started bringing home pieces from the galleries on La Cienega Boulevard. At first he was more concerned with their cost.

Then, through a shared interest in politics (he is a lifelong Democrat), he met Taft Schreiber, a vice president of MCA Universal who had an impressive collection of 20th-century art. Suddenly, a world beyond tract homes and insurance products revealed itself, to which art was the social entrée.

A stairway at The Broad, and El Anatsui ‘Red Block’ 2010 © El Anatsui, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY

The Broads began conventionally enough, buying a Miró, a Matisse, a Modigliani and (for $95,000) an 1889 Van Gogh drawing of houses with thatched roofs, from his period in Arles. But the Van Gogh was in such a delicate condition that it couldn’t be exposed to daylight and was kept in Eli’s underwear drawer. They finally exchanged it for a Robert Rauschenberg Red Painting, a blood-red panel with fabric attached, which is now prominent in The Broad’s collection, and they never again returned to 19th-century art.

Instead, they have focused on artists from their own time, whom they try to get to know and understand. That is how you build a great collection, they contend — although they continue to miss their Van Gogh, which they discuss as if grieving for a child gone missing. ‘Oh, I would love to have kept it,’ Edye tells me wistfully, when I meet the Broads at their house in Brentwood.

Their home, part of a three-acre estate, is a spectacular stucco-and-glass palace with a 55-ton steel roof shaped like a flower. It is at the end of a long, grassy drive that passes through grounds dotted with sculptures by Picasso, Richard Serra and David Smith. The house is large and echoey. It is Edye’s domain, and she rotates its collection of 70-odd artworks, which includes a 1933 Miró, a Giacometti sculpture, a Calder mobile and — dominating one wall of the drawing room when I visited— Anselm Kiefer’s vast, traumatised landscape of Let A Thousand Flowers Bloom. She also collects pre-Columbian gold jewellery. ‘Edye has a broader view of art than I do,’ Eli nods graciously. ‘But the Met has a better collection,’ she replies.

In a recess off the drawing room are framed photographs of Eli with other powerful men, including US presidents. Broad was once spoken of as a future ambassador to Britain or Germany. Would he ever have run for US president? ‘Oh, please!’ says Edye, horrified. He looks stoic: ‘I don’t have the personality or the patience to be a politician,’ he quietly admits.

It’s Eli who drives their art collection. On their journey together, Edye sometimes instigates but more often navigates, offering pertinent directions and moderating the driver’s natural impatience. Whereas Edye is often seen wearing a comfortable black pantsuit, Eli is always pictured in a smart suit and tie, not a silver hair out of place; and even at home, he is dressed the same. He is tall, trim and well-made for his age, and is warmer and more playful than he’s often characterised.

Eli and Edye have spent decades investigating auctions, galleries and studios, researching and interrogating artists, and visiting international art fairs where a hound dog may pick up a juicy bone. In Britain, they flew by helicopter to help Damien Hirst dip a shark in formaldehyde. In New York, they discovered Jean-Michel Basquiat living in a basement, and bought his early work for $5,000 a piece. All the time, their collection grew, spilling out from the three homes they own, until there were 2,000 artworks filling five warehouses; and then they knew that they must have their own building and open up their art to the people of Los Angeles.

In foreground: John Ahearn ‘Raymond and Toby’ 1989; From left, Keith Haring ‘Red Room’ 1988; Keith Haring ‘Untitled’ 1984; Jean-Michel Basquiat ‘Gold Griot’ 1984. © John Ahern. Keith Haring artworks © Keith Haring Foundation © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, New York 2016

The Broad is on the site of a former parking lot, in unfashionable downtown LA. The city has become a vital cause for Broad. He is intent on cementing its growing reputation as the world centre of contemporary art.

For many years, until the Hammer Museum opened in 1990, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) was the only place big enough for Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin, Edward Kienholz and other successful West Coast modernists to exhibit locally; otherwise, they had to show in New York.

Broad is trying to make up for those lost years. ‘LA has been very good to us,’ he explains. ‘It’s a meritocracy, and that is important to us. In other cities, you’ve got to have come from the right family or the right religion or politics, but you can come here, and if you’ve got ideas, energy and leadership ability, you can get things done.’

So, in 1979, he became founding chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA), which he was later instrumental in rescuing from potential insolvency. He gave $50 million to build the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM), which is part of the sprawling LACMA campus. And although he has little interest in music, Broad also helped raise $220 million to realise one of LA’s biggest but most troubled millennial projects, the Walt Disney Concert Hall, which eventually opened in October 2003. Designed by Frank Gehry, it is now the home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and considered an architectural masterpiece.

Broad’s wheeler-dealing at these institutions sometimes overlapped with his ambition to find a permanent home for his own art collection; the surprise for many was where he finally found it. Santa Monica, Culver City and Beverly Hills had vied for his dollar, but the cheaper price of land downtown finally swayed him.

This has traditionally been the central business district of LA, but it has long been in decline and there are still few people who linger here for pleasure. When Raymond Chandler wrote about Los Angeles as a ‘sunny place for shady people’, he was describing downtown, a shabby zone of flophouses, parking lots and men with pulled-down hats.

Its steep descent was halted in the early 2000s, when Broad convened a committee for the redevelopment of Grand Avenue, with himself as chairman and Gehry as architect of a $1.8 billion master plan to build condos, shops and offices. The Broad and the Disney Concert Hall are now critical to the commercial revival of downtown. These twin beacons of cultural and social improvement sit within a hundred yards of each other.

The Disney hall resembles an elegant ship, unfurling sails of bright stainless steel, and is unmistakably by Gehry. The Broad is distinctive in its own way. Its square shape is enveloped by a white carapace of fibreglass and concrete, already christened ‘The Veil’, that has been favourably likened to a honeycomb, but also to a cheese-grater and ‘the discarded foam packaging of a sparkling new gift’, in the words of architectural critic Edwin Heathcote. Its architect is the hot New York firm of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, previously best known for its role in creating Manhattan’s High Line park out of a disused railway line.

The Vault at The Broad, from left: Albert Oehlen ‘Abstand’ 2006; Keith Haring ‘Untitled’ 1984; George Condo ‘Double Heads on Red’ 2014. © Albert Oehlen. Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

Inside the museum lies another novelty. The bulk of Broad’s collection is stored in a second-floor space known as ‘The Vault’, ready to be taken out for exhibition or loaned by the Broad Art Foundation to art institutions around the globe. Visitors strolling around the museum are allowed to glimpse this archive through windows in the walls of the central staircase.

The various galleries exhibit about 250 artworks. To walk the skylit third floor, which is suffused by beautiful natural light, is a particular delight. ‘We didn’t want it to be a dark museum,’ Broad tells me. ‘Most museums are dark and uninviting. Not this one.’

An ‘arts district’ is now cohering around The Broad, the Disney Concert Hall and nearby MoCA, and by 2020 a new metro station, under construction beside The Broad, will whisk visitors here from as far away as Long Beach and Santa Monica. By Christmas 2015, 200,000 people had visited The Broad, double the expected attendance, and advance reservations were booked well into 2016.

These numbers are gratifying to Broad, a keen populariser of art who has made admission free. He has also announced an endowment for The Broad of $200 million, ‘which is greater than the endowment of LACMA and the Museum of Contemporary Art combined’.

Broad’s munificence has never been in doubt; few colleagues have ever seen him as a team player, however. I ask The Broad’s director, Joanne Heyler, who has worked with him for 20 years, to describe their relationship. She laughs and replies: ‘I would say that he can be challenging — and I think he’d be happy to read that, actually.’

Exterior detail from The Broad Museum, Los Angeles

A conservative list of his sparring partners over the years would include art dealers, museum directors and trustees, rival collectors such as entertainment mogul David Geffen (whose Geffen Contemporary is a museum within MoCA), and especially some of the architects he has hired, including Renzo Piano, with whom he fought over the cost of the roof at BCAM, and Gehry, LA’s most celebrated architect.

Four years ago, he wrote a remarkable memoir and business manual, now published in five languages, which he slyly called The Art of Being Unreasonable, because everyone expects him to be so. In fact, the title is from an inscription on a paperweight his wife gave him. This is George Bernard Shaw’s adage that the reasonable man adapts himself to the world, while the unreasonable one persists in adapting the world to himself, a sentiment that Broad has taken to heart. He argues that he could only have achieved great things by being unreasonable, no matter what the cost.

Even his adversaries would acknowledge the importance of The Broad and its collection. Within its 120,000 square feet are 35 works by Jeff Koons, 42 by Jasper Johns, 124 Cindy Shermans, 28 Andy Warhols, 19 Cy Twomblys, 14 Damien Hirsts, 13 Robert Rauschenbergs and 33 other Lichtensteins, as well as nearly all the stars of the modern and contemporary art game: Basquiat, Christopher Wool, Glenn Ligon, Takashi Murakami, and so on.

In the centre of a gallery devoted to Jeff Koons, perhaps The Broad’s biggest prize, a shiny Balloon Dog (Blue) stands pricked to attention, next to Koons’s steel bouquet of Tulips. The eye is then drawn across the room to an emblematic piece of gold-and-white porcelain. This is Michael Jackson and Bubbles, a boy and his pet chimp captured in an embrace of queasy kitsch that nails the peculiarity of Jackson’s personal story.

The inaugural exhibition showed more than 60 artists: mainly Americans, some Germans and a few Brits (including Hirst and Jenny Saville, but no Freud, Bacon, Doig or even, despite this being LA, David Hockney). It represents the taste of one man, not an institutional committee, and Heyler says that ‘Eli is more often moved by content that is political or historical or connected to the real world, so to speak. He’s a little more attracted to social content.’

But what draws the biggest crowds on my visit are two installations that are gentle and enigmatic. The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is a veteran of most post-war avant-garde movements — and one whose polka-dot works prefigure Hirst’s spot paintings — yet she still seems remarkably fresh. Her trippy Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away conjures deep space out of mirrors and LEDs, and is like a brilliant mobile in a child’s bedroom.

The other installation, by the young Icelander Ragnar Kjartansson, a hipster artist and musician, offers an audio-visual experience. The Visitors pans across nine monitors as it slowly searches the rooms of a crumbling mansion in upstate New York; in each room, different musicians are condemned to repeat the same plangent, ragged song. Kjartansson himself appears, half-submerged in a soapy bath, happily clutching his guitar.

It’s compelling but undeniably whimsical, and I can’t help but wonder what an old toughie like Eli makes of it — and, indeed, how he and Edye view their whole collection, all 2,000 pieces of it. Can they actually like every single artwork? ‘We wouldn’t have bought any of them if we didn’t like them,’ Edye says quickly. Eli suggests that buying young artists’ work was always a gamble: ‘We didn’t know what would happen with Basquiat or Keith Haring when we bought them. People now say they were trophies. They sure weren’t trophies at the time.’

Eli and Edythe Broad at their home, with Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, 1954. Portrait by Roger Davies courtesy of Architectural Digest. Artwork: © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London, 2020

He thinks a bit, and then he explains, very carefully, something of his philosophy. ‘Art for us is an educational experience,’ he says. ‘Collecting isn’t just buying fine objects. Being able to know artists, to see how they view society, it’s a great experience, and it’s fun. Life would be boring if I spent all my time with lawyers, accountants, bankers and other business people.’

And now my time with him is up. There is some pleasant chit-chat, then he rises and his lanky frame gradually recedes down the long, stone halls. But before he disappears, I ask him to sign his book. Above his signature, he has put two words. They read: ‘Anything else!’ An exclamation, thankfully, not a question.

Source: Christie’s