Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1900-1906. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It has been reported that the $450 million price of the rediscovered Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (c. 1500), was due to a vanity war between the Saudi royal family and the de facto ruler of the United Arab Emirates, who both mistakenly thought they were bidding against their art-collecting Gulf rival, the Qatari royal family. That a Russian oligarch had consigned the picture expecting to sell it at a loss (in order to bolster his court case against a Swiss freeport-owning art dealer), but unexpectedly reaped a $300 million gain, reveals an interesting truth: The highest segment of the market is often more about the rivalry and whims of a tiny group of billionaires than it is about the actual art.

The picture ultimately found its way to the Louvre Abu Dhabi after the Saudis reportedly flipped it for a mega-yacht, so I guess you can score one for the museum-going public. But museum officials I know are still annoyed by the whole saga. For them, art is supposed to exist beyond economics. Don’t believe me? If you get a chance to meet a curator, ask how much one of her museum’s great pictures is worth. You’ll get either an unsatisfying “priceless” or “incalculable,” or a remember-the-good-old-days talk about how art has become commoditized. But of course, no picture is priceless.

So what are the masterpieces lining museums’ walls worth to the people who could actually afford them? As a thought experiment, I asked several of the world’s great collectors and dealers (our clients) which pictures in U.S. museums they most want to own, and how much they would pay to own them. The pictures that came up again and again shared three characteristics: historical significance, celebrity, and contemporary appeal.

Historical significance is really a matter of influence. University of Chicago economist David Galenson, who studies the art market, told me that “pictures that have the greatest influence on the practice of other artists and the culture at large become canonized and sell for the highest prices.”

Celebrity is even simpler. Some works are famous for being famous. Pictures like Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948) at MoMA or Maxfield Parrish’s Daybreak (1922) attain a level of populist appeal that far outstrips their art historical influence. Some celebrity works are also significant. For collectors, owning a celebrity work delivers a jolt of status.

Contemporary appeal is a function of whatever is in vogue among the world’s 50 largest collectors. The preferences of this 0.000000007% of the world’s population drive prices at the highest end of the market. Genres go in and out of favor. Late 19th-century millionaires wanted academic realists, early 20th-century robber barons favored Dutch and Italian masters, 1980s Japanese tycoons acquired Post-Impressionists. George Wachter, the Americas chairman of Sotheby’s, said today’s collectors “want an in-your-face, immediacy and intensity. Brash is in.”

The 10 pictures in U.S. museums I believe would make the highest price in my dystopian auction scenario (think the Bolshevik sale of Hermitage masterworks in the 1930s) rate highly across these three areas.

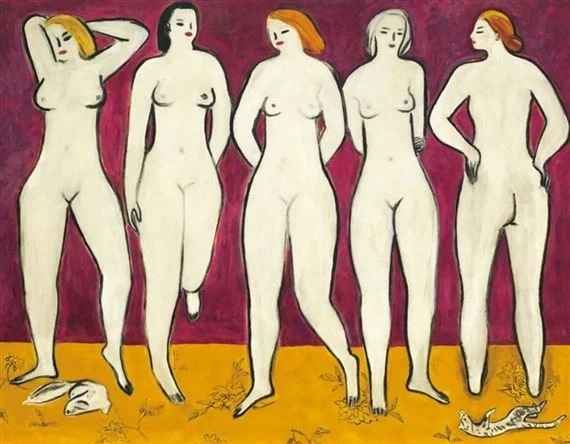

$1.2 billion—Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907. © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s hard to convey how badly top collectors want to own this painting. Hands down, it wins the “If You Could Own One Painting” game amongst billionaires. And why not? It’s the most important (and most frequently referenced in textbooks) painting by the most important artist of the 20th century. It’s the musical equivalent of having sole ownership of Mozart’s “Symphony No. 41.” Art historian Miles Unger called it “the cultural equivalent of Lenin pulling into the Finland station in 1917.” I see it as the fulfillment of the modernist project, started in 1863 by Édouard Manet with Luncheon on the Grass (the 19th century’s most significant and valuable picture), to eliminate linear perspective and flatten the body. Given its perfect mix of significance, celebrity, and contemporary appeal, it’s the ultimate cultural trophy. This is a conservative estimate. The painting is exponentially more valuable than Picasso’s other grand statements, his Blue Period La Vie (1903) at the Cleveland Institute of Art and his Rose Period Family of Saltimbanques (1905) at the National Gallery of Art. Picasso’s current auction record for 1955’s Les femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), which sold for $179 million at Christie’s in 2015, isn’t in the same universe as what this picture would bring.

$1 billion—Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s a celebrity with intellectual depth—strangely familiar upon first glance with a friendly façade that conceals a tortured soul. Like the Mona Lisa, the picture is plagued by a permanent arch of iPhone-wielding selfie-takers who come to prove they’ve seen the picture rather than to actually see it. While van Gogh’s sunflowers and self-portraits may have more directly influenced art history, TheStarry Night has become the most iconic image of our most mythologized artist. Bidding would be global and fierce. One Asian billionaire told me that he’d liquidate his global empire to own the painting.

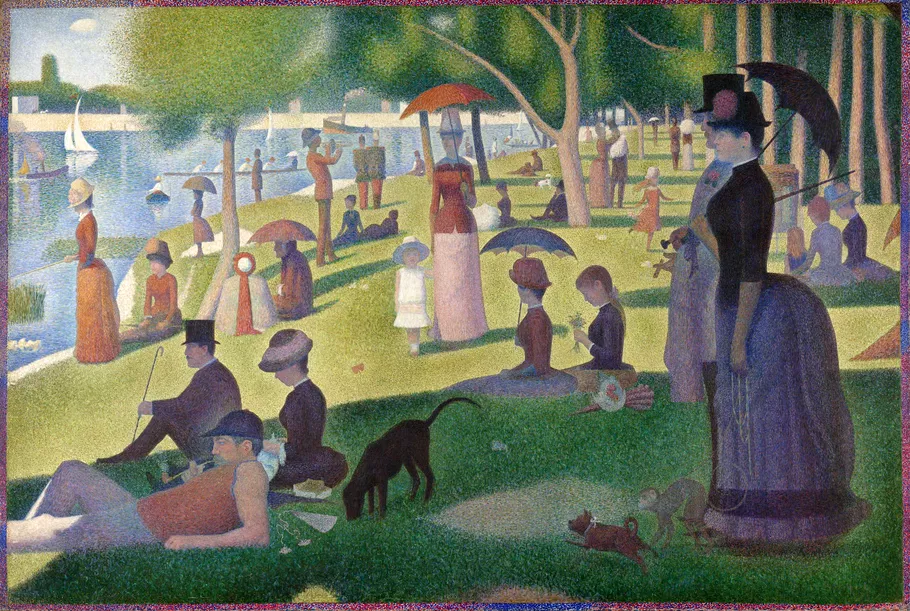

$700 million—Henri Matisse, The Joy of Life (1906), Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Henri Matisse. Le Bonheur de vivre, also called The Joy of Life, between October 1905 and March 1906. BF719. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

After a century hiding in a poorly lit second-floor corner of Alfred Barnes’s collection in Merion, Pennsylvania, the picture now hangs in a poorly lit second-floor corner of the newly opened (and far superior) space in downtown Philadelphia. Less well known than Matisse’s Dance I (1909) at MoMA or Woman with a Hat (1905) at SFMOMA, it is far more significant. It’s Fauvism’s grand statement, the picture that launched the 20th century, tormenting Picasso’s imagination and driving him towards Cubism. Bidding would be less broad than for others, but the right connoisseurs would drive the price of this work well into the $700 million range.

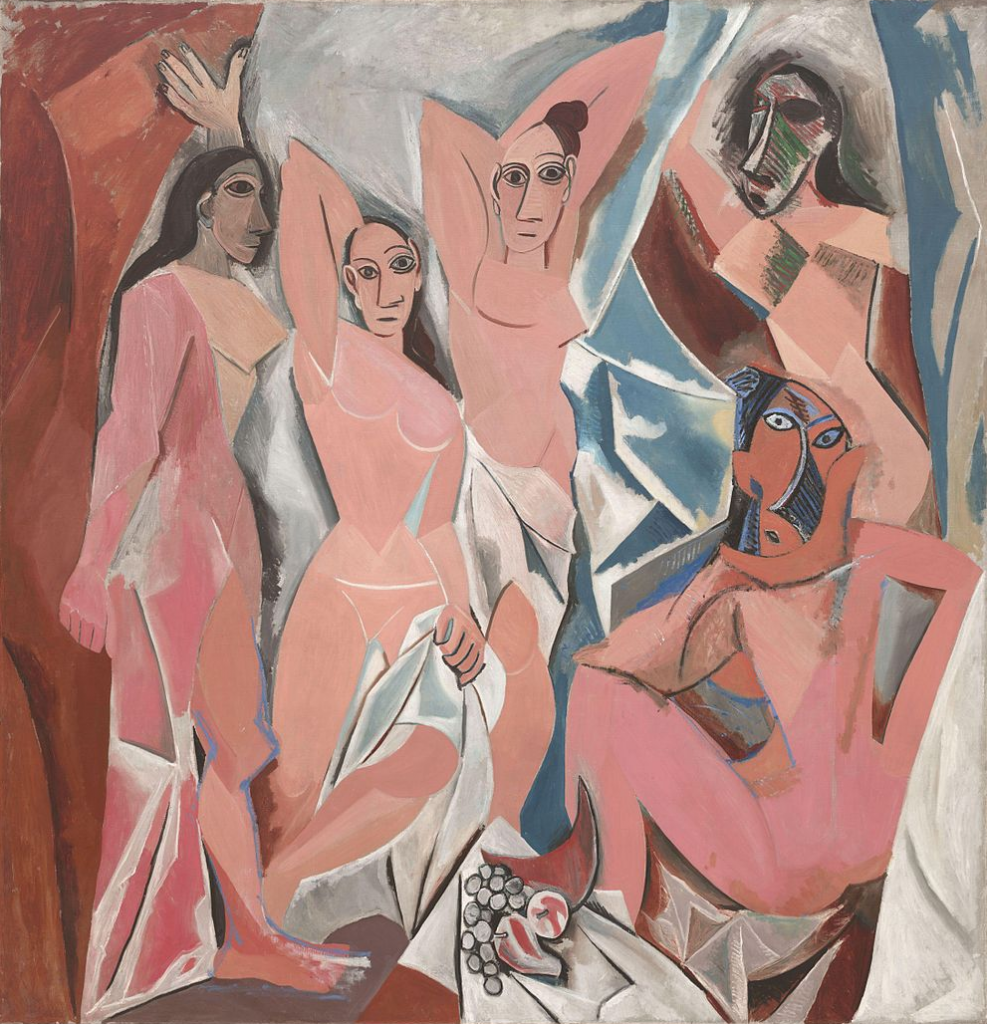

$650 million—Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte (1884), Art Institute of Chicago

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884-1886. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a massive work painted with an even bigger mission: to put modern art on a scientific footing. It’s almost a cliché to say it, but Seurat did for color what Einstein did for time and space. He introduced relativity by demonstrating that the relationship among colors, not the colors themselves, can create a visual impression. Like a three-star Michelin rating, La Grande Jatte is the rare picture worth a special journey to experience in person. A pillar of Chicago’s cultural identity, it possesses economic utility in addition to its cultural significance. Bidding from Asia and the Middle East would be aggressive.

$500 million—Paul Cézanne, The Large Bathers (1900–06) and The Card Players (1892), Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players (Les Joueurs de cartes), 1890–1892. Courtesy of the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

Cézanne’s two great pictures are equally momentous, but for different reasons. The Large Bathers is one of his most influential pictures, laying the groundwork for Fauvism, Cubism, and every other “ism” throughout the 20th century, while The Card Players has become a celebrity in its own right, an early archetype of modern alienation and disaffection (if updated today, he might depict a family hypnotized by their iPhones). A smaller version of The Card Players sold in 2011 to the Qatari royal family for a reported $250 million. Both paintings would stoke total warfare in the auction room.

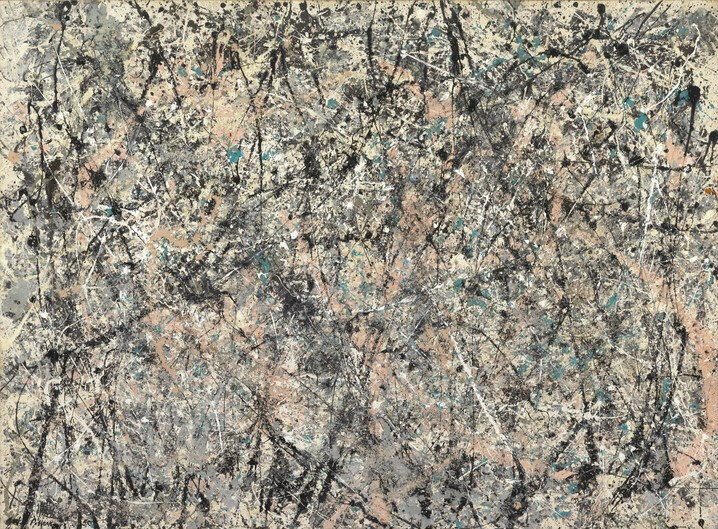

$450 million—Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) (1950), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist), 1950. © 2018 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

European culture never quite recovered from Pollock’s American-ness. His American aggression, his American scale, even his American death (mangled in automotive steel) breathed new energy into high art and shifted its epicenter from Paris to New York, where it has remained ever since. The atmospheric Lavender Mist is Jack the Dripper at his pinnacle, his mythologized process of intuition, chance, and control at its most poetic. Pollock’s works have already gone for $200 million in the private market, and this is his most sought-after work among collectors.

$400 million—Henri Matisse, The Red Studio (1911), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Henri Matisse, “The Red Studio” (1911). Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

It’s impossible to overstate this painting’s art historical influence. The canvas is so consistently mined by artists, from Mark Rothko to Frank Stella, that its pure color and simplicity no longer shock us. Perhaps a cliché to say, but its color would attract intense Chinese bidding. I’d also expect Middle Eastern collectors to make a run, given the traditional Islamic influences in the work, which stemmed from Matisse’s time in Muslim Spain.

$350 million—Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance (c. 1664), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

The once-forgotten Vermeer has staged one of the greatest comebacks in art history. Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker noted that he has “displaced Raphael,” whose Alba Madonna (c. 1510) once held the record for most expensive picture, “as Europe’s cynosure of artistic perfection.” Perhaps we want what we can’t have: Only one Vermeer has appeared at auction in the last 90 years, a third-rate reattribution that sold for $30 million in 2004. This picture, a subtle image of temperance and contemplative reasoning, is the perfect Vermeer, and has a slight edge over the more contemporary-feeling Girl with the Red Hat (c. 1665).

$350 million—Willem de Kooning, Excavation (1950), Art Institute of Chicago

Willem de Kooning, Excavation

He’s been called America’s answer to Picasso, and Excavation is his most important work. Hurried, slashing, yet balanced, de Kooning takes up Cubism’s challenge, dissolving the body without losing the figure. With his Interchanged (1955) selling for $300 million privately according to the New York Times, this estimate may be conservative.

$350 million—Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci (c. 1478), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci [obverse], c. 1474/1478. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

We’re in the midst of Leonardo mania, and not even the dazed, uneven face of Ginevra de’ Benci can escape it. Purchased in 1967 by D.C.’s National Gallery for a then-record price of $5 million from the Prince of Liechtenstein, it’s the sole Leonardo painting in the Western Hemisphere. A trial run for future greatness, this portrait of a young Florentine previews the elusive smile, smoky skin, and hallucinatory background of a more celebrated portrait he’d one day paint. Still, it would be a stretch to expect Salvator Mundi-level folly for this work.

Written by Evan Beard

Source: Artsy