Never before have the terms “great artist” and “masterpiece” been used arbitrarily like now. The habit of using “indiscriminately” titles with far-reaching and important values about an “extremely famous artist” or a “classic work” has made art lovers bewildered, not know which quantity to use as a measure of value.

To partially answer those “bewilderment”, Viet Art View sincerely send to art lovers two translations, “What Makes a Great Artist?” and “What is a masterpiece?”, thereby wanting to give art lovers an overview of the true meaning of the two phrases “great artist” and “masterpiece”. From there, we can see more clearly and calmly when there is a “reference”… Sincerely invite readers to follow up.

Before we learn how to make a masterpiece, we have to understand the process of making masterpieces. Someone has to put the paint on the canvas and make something out of it that we call art. The same goes for sculpture or any other work of art or style. Then someone has to grab a writing utensil, usually art historians, critics, and take it to the page to form words, texts, expressions on great works of visual arts. Images and sounds we build in our minds shine for the world to see. They are creative and one of a kind. Why are they greatest works? Because of the value placed on them by their creator?

Masterpiece is the most overused word in the art world. Dubbing something a ‘masterpiece’ helps justify higher prices and signals the quality of the art.

And we all know that not everything done by a master such as Picasso or Van Gogh is necessarily a masterpiece.

Today, the word “master” or “masterpiece” has lost its meaning because it is not based on anything tangible in the modern world. It becomes just a pretty word that has lost its original purpose. Anyone can say a piece of art is a masterpiece as long as they are connected to the art elite, and then the piece is stamped as a masterpiece even if it is not.

So…

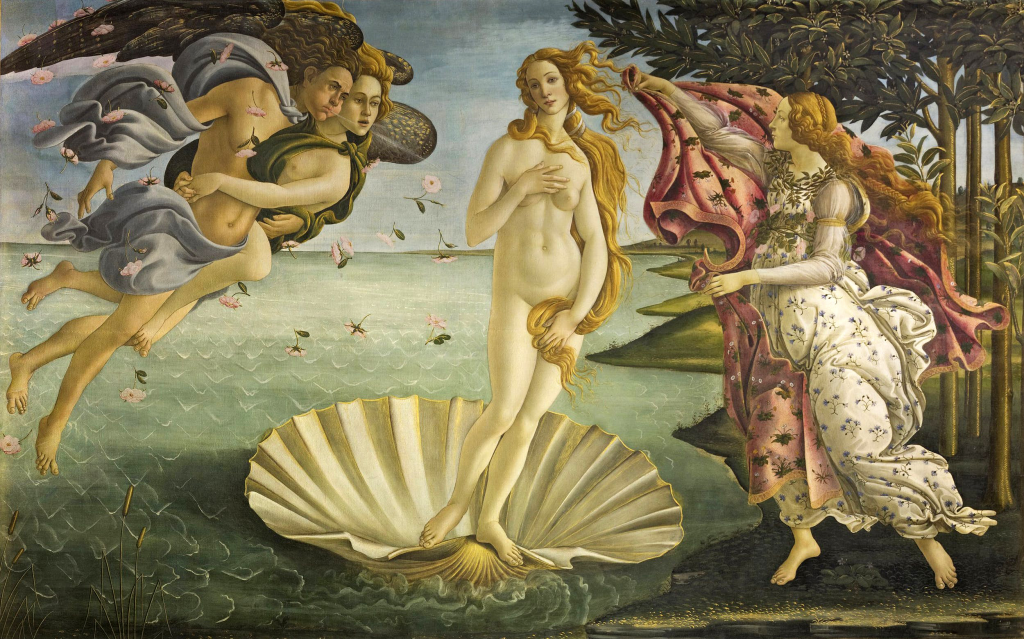

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486). Tempera on canvas. 172.5 cm × 278.9 cm (67.9 in × 109.6 in).

Uffizi, Florence. Source: Wikipedia.

What makes a masterpiece?

A Masterpiece is the work of an artist who has been absorbed by the spirit of his/her times and can transform personal experience into a universal one. Masterpieces make us forget the artists, and instead direct our attention to the artist’s works. We may wonder how a particular work was executed, but for the time being, we are transposed, so deeply brought into this creation that our consciousness is expanded.

Although there are differentiating criteria on the specific elements involved in selecting a masterpiece, there are common qualities that every masterpiece shares. Some feelings must be evoked, whether it’s curiosity, awe, or disgust. There should be style, technique, balance, and harmony. It is helpful to discuss perspective and form, but still, this would not describe that elusive element essential to any moving work, and the motive is another important factor.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, Oil on poplar panel, 77×53 cm, Source: Wikipedia

Masterpiece defined

“Masterpiece” has its troublesome edge, though. Some contemporary scholars dismiss the term as an elitist designation, used to exclude whole categories of art or to lend an air of mystification to critical judgments. And the general public sometimes embraces certain works as “masterpieces” based mostly on their celebrity and fame.

The term “masterpiece” originated in the Middle Ages when apprentice artisans had to prove their skills by submitting exemplary work for approval by the guild that governed their trade — carving, metalwork, enameling. If the piece demonstrated mastery of the craft, the apprentice would be promoted to master.

A masterpiece is something that stands the test of time and is viewed as a masterpiece from generation to generation. Secondly, it must influence generations of artists and change the way that people look at the medium — be it painting, sculpture, decorative art or whatever. It must be so original that once you’ve seen it, you’re indelibly influenced by its power, and any artist who goes in that direction is accused of studying under or being in the shadow of the original.

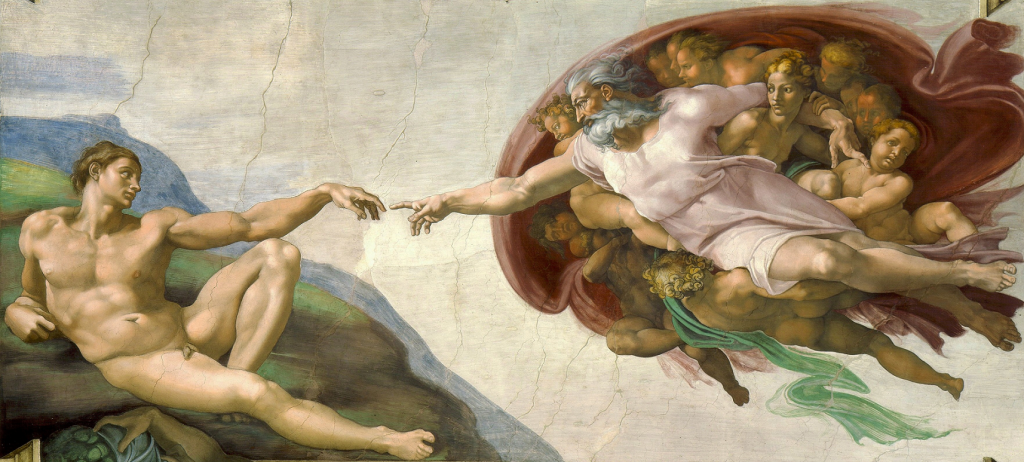

Michelangelo (1475–1564), Creation of Adam, Part of Sistine Chapel ceiling, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Evolution of the masterpiece

The meaning evolved under the influence of connoisseurs, who might judge art on the distinctiveness of its design, energy, rarity, quality, age, provenance, subject matter, universal appeal, originality, or scholars who often concern themselves with the history and authenticity of a piece.

“Nothing is a masterpiece – a real masterpiece – till it’s about two hundred years old. A picture is like a tree or a church; you’ve got to let it grow into a masterpiece. Same with a poem or a new religion. They begin as a lot of funny words. Nobody knows whether they’re all nonsense or a gift from heaven. And the only people who think anything of ’em are a lot of cranks or crackpots, or poor devils who don’t know enough to know anything.” — from the book The Horse’s Mouth, Joyce Cary

Titian (1490–1576), Amor Sacro y Amor Profano, 1514, Oil on canvas, 118×279 cm, Source: Wikimedia Commons

A continuing education

We’re all enslaved by our prior experiences. One might appreciate an artist because he’s captive to his knowledge base in whatever art history. But seeing more broadens the understanding and appreciation of the evolution of taste, scholarship, and personal development. By looking at exhibitions, people can continue to develop and expand their knowledge of what a masterpiece can be.

“The Mona Lisa, that really is the ugliest portrait I’ve seen, the only thing that supposedly makes it famous is the mystery behind it,” Katherine admitted as she remembered her trips to the Louvre and how she shook her head at the poor tourists crowding around to see a jaundiced, eyebrow-less lady that reminded her of tight-lipped Washington on the dollar bill. Surely, they could have chosen a better portrait of the First President for their currency?” — from the book Brushstrokes of a Gadfly, E.A. Bucchianeri

Raphael, School of Athens, 1509–1511, Fresco, 500×770 cm, Source: MVSEI VATICANI

Written by Alina Livneva

Source: VÎRTOSU ART GALLERY