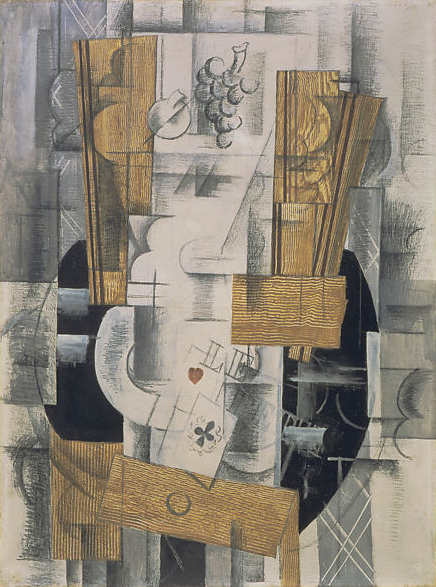

This exhibition will offer a radically new view of Cubism by demonstrating its engagement with the age-old tradition of trompe l’oeil painting. A self-referential art concerned with the nature of representation, trompe l’oeil (“deceive the eye”) beguiles the viewer with perceptual and psychological games that complicate definitions of truth and fiction. Many qualities seen as distinct to Cubism were, in fact, exploited by trompe l’oeil specialists over the centuries: the emphatically flat picture plane; the invasion of the “real” world into the pictorial one; the mimicry of materials; and the inclusion of new print media and advertising replete with coded references to artist, patron, and current events. In a contest of creative one-upmanship, the Cubists Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Pablo Picasso both parodied classic trompe l’oeil devices and invented new ways of confounding the viewer. Along with Cubist paintings, sculptures, and collages, the exhibition will present canonical examples of European and American trompe l’oeil painting from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries; is taking place at the Metropolitan Museum, running until January 22, 2023.

THE CURTAIN BY PARRHASIUS

“Parrhasius entered into a competition with Zeuxis, who produced a picture of grapes so successfully that birds flew up to it. Whereupon Parrhasius painted such a realistic representation of a curtain that Zeuxis requested that the curtain should be drawn. When Zeuxis realized his mistake, he yielded up the prize, saying that whereas he had deceived birds, Parrhasius had deceived him, an artist.” — Pliny the Elder (Natural History, a.d. 77), on the origins of pictorial illusionism in a contest between two ancient Greek painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasius.

One of the oldest forms of Western painting, trompe l’oeil (French for “deceive the eye”) would seem to have little in common with the anti-illusionism of the Cubists; this exhibition reveals otherwise. A selfreferential art that calls attention to its own artifice, trompe l’oeil, like Cubism, involves the viewer in perceptual and psychological games that complicate definitions of reality and authenticity. Trompe l’oeil easel painting flourished in midseventeenth century Europe, inspired by Pliny the Elder’s legendary account of how a painted image could be taken for the real thing—at least momentarily. Typically, artists augmented their “counterfeits” by including painted simulations of handwritten texts and printed matter, blurring the boundaries between the private and the public spheres, and between fine art and popular culture. Frequently disparaged as mere copyists, they showed off their ingenuity with unexpected sleights of hand and elevated the humble genre of still life with commentary on contemporary affairs and morality.

The reputation of trompe l’oeil painting declined precipitously during the nineteenth century, which may explain why its connections to Cubism have been largely overlooked. Yet Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Pablo Picasso similarly laid bare the conventions of verbal and visual representation, filled their pictures with allusions to art and art making, and upended hierarchies of taste. They parodied and emulated trompe l’oeil strategies in a three-way contest of creative one-upmanship that accelerated with the introduction of collage techniques in 1912. The presence of actual things in the picture—newspaper clippings and illusionistic wallpapers—resulted in previously unimaginable levels of paradox and new ways of confounding the mind. Like the trompe l’oeil artists of earlier centuries, the Cubists raised provocative questions about originality, truth, and falsehood that remain relevant today.

Trompe l’Oeil Still Life with Flower Garland and Curtain. Adriaen van der Spelt (Dutch, ca. 1630–1673). Frans van Mieris the Elder (Dutch, Leiden 1635–1681 Leiden). 1658.

Still Life with Four Bunches of Grapes. Juan Fernández, “El Labrador” (Spanish, documented 1629–1657). ca. 1636.

Violin and Grapes. Pablo Picasso (Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France). 1912.

Violin and Engraving. Juan Gris (Spanish, Madrid 1887–1927 Boulogne-sur-Seine). 1913.

Still life with Compote and Glass. Pablo Picasso (Spanish, Malaga 1881–1973 Mougins, France). 1914-1915.

Fruit Dish, Ace of Clubs. Georges Braque (French, Argenteuil 1882–1963 Paris). 1913.

Still Life with Violin, Ewer, and Bouquet of Flowers. J. S. Bernard (probably French, active 1650s–1660s). 1657.

Still Life with Box of Jelly, Bread, Salver with Glass, and Cooler. Luis Meléndez (Spanish, Naples 1716–1780 Madrid). 1770.

Source: Met Museum